```

68 | # ### ### ####### Текст со всякими звёзд*чками* и другими символами

69 | ```If you’ve enjoyed the guide, share it with a friend and help us reach more people.

85 | 86 |If you’ve enjoyed the guide, share it with a friend and help us reach more people.

85 | 86 |Our co-founder and president, Will MacAskill, was a graduate student at the time in 2011. He's now an associate professor of Philosophy. Our founding board also contained Dr. Toby Ord and Dr. Nick Beckstead, who have both worked as researchers at the Future of Humanity Institute in Oxford (and Toby still does). They advise us on our research. We're affiliated with the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and the Future of Humanity Institute, with whom we shared an office for most of our history (though currently we’re based in Berkeley, CA). We’re also advised on our research by several other academics, such as Dr. Owen Cotton-Barratt, formerly a maths lecturer at Oxford and today a researcher at FHI in Oxford. See more on meet the team.`] The aim is to provide the advice we wish we’d had – easy to use, transparently explained and based on the best evidence available. 58 | 59 | In 2012, we raised funding and hired a team. We’re a non-profit supported by individual donations, and we don’t take money from advertisers or recruiters, so all our advice is impartial. 60 | 61 | Since then, we’ve spoken to hundreds of experts, spent hundreds of hours reading the relevant literature, and conducted our own analyses of the many job options available. We still have a lot to learn, these questions are difficult to settle, and we’ve made some mistakes; but we don’t think anyone else has done as much systematic research into this topic as we have. 62 | 63 | Among the things we’ve learned: if you want a satisfying career, “follow your passion” can be misleading advice; you might be able to do more good as an accountant than a charity worker; and that many approaches to making the world a better place don’t work. We’ve also come up with new ways to approach age-old questions like how to figure out what you’re good at, and how to be more successful. 64 | 65 | Most importantly, we’ve learned that over your career, if you choose well, you can likely do good on the scale of saving hundreds of lives or more, while doing work that’s more enjoyable and fulfilling too. 66 | 67 | As of today, thousands of people have significantly changed their career plans based on our advice. These readers have pledged more than $30 million to some of the world’s most effective charities, founded ten new organizations focused on doing good, and helped to start the global “effective altruism” movement, which aims to use evidence and reason to determine the most effective ways to help others. Some of our readers are saving hundreds of lives in international development, some are working on neglected areas of government policy, some are developing ground-breaking technology, and others have used our research to figure out their own paths. 68 | 69 | ## What you’ll learn 70 | 71 | See a summary of the 12 articles in one page. 72 | 73 | The first six articles discuss which options will be most fulfilling and have the highest-impact over the long-term: 74 | 75 | 1. What makes for a dream job? 76 | 1. Can one person make a difference? 77 | 1. How to have a real positive impact in any job. 78 | 1. How to choose which problems to focus on. 79 | 1. What are the world’s biggest and most urgent problems? 80 | 1. What types of jobs are high-impact? 81 | 82 | The next four cover how to narrow down those options and succeed by investing in yourself: 83 | 84 | ``` 85 |

This is the easiest option. We’ll also tell you about our live, in-person workshops, and how to get one-on-one advice. You’ll be joining over 100,000 subscribers, can unsubscribe in one click, and we’ll never pass on your email.

115 | 121 | 122 |It’s only 90 minutes and covers the key ideas, in less depth.

124 | 125 |It’s available in Kindle or paperback.

127 | 128 |Our co-founder and president, Will MacAskill, was a graduate student at the time in 2011. He's now an associate professor of Philosophy. Our founding board also contained Dr. Toby Ord and Dr. Nick Beckstead, who have both worked as researchers at the Future of Humanity Institute in Oxford (and Toby still does). They advise us on our research. We're affiliated with the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and the Future of Humanity Institute, with whom we shared an office for most of our history (though currently we’re based in Berkeley, CA). We’re also advised on our research by several other academics, such as Dr. Owen Cotton-Barratt, formerly a maths lecturer at Oxford and today a researcher at FHI in Oxford. See more on meet the team.`] The aim is to provide the advice we wish we’d had – easy to use, transparently explained and based on the best evidence available. 58 | 59 | In 2012, we raised funding and hired a team. We’re a non-profit supported by individual donations, and we don’t take money from advertisers or recruiters, so all our advice is impartial. 60 | 61 | Since then, we’ve spoken to hundreds of experts, spent hundreds of hours reading the relevant literature, and conducted our own analyses of the many job options available. We still have a lot to learn, these questions are difficult to settle, and we’ve made some mistakes; but we don’t think anyone else has done as much systematic research into this topic as we have. 62 | 63 | Among the things we’ve learned: if you want a satisfying career, “follow your passion” can be misleading advice; you might be able to do more good as an accountant than a charity worker; and that many approaches to making the world a better place don’t work. We’ve also come up with new ways to approach age-old questions like how to figure out what you’re good at, and how to be more successful. 64 | 65 | Most importantly, we’ve learned that over your career, if you choose well, you can likely do good on the scale of saving hundreds of lives or more, while doing work that’s more enjoyable and fulfilling too. 66 | 67 | As of today, thousands of people have significantly changed their career plans based on our advice. These readers have pledged more than $30 million to some of the world’s most effective charities, founded ten new organizations focused on doing good, and helped to start the global “effective altruism” movement, which aims to use evidence and reason to determine the most effective ways to help others. Some of our readers are saving hundreds of lives in international development, some are working on neglected areas of government policy, some are developing ground-breaking technology, and others have used our research to figure out their own paths. 68 | 69 | ## What you’ll learn 70 | 71 | See a summary of the 12 articles in one page. 72 | 73 | The first six articles discuss which options will be most fulfilling and have the highest-impact over the long-term: 74 | 75 | 1. What makes for a dream job? 76 | 1. Can one person make a difference? 77 | 1. How to have a real positive impact in any job. 78 | 1. How to choose which problems to focus on. 79 | 1. What are the world’s biggest and most urgent problems? 80 | 1. What types of jobs are high-impact? 81 | 82 | The next four cover how to narrow down those options and succeed by investing in yourself: 83 | 84 | ``` 85 |

This is the easiest option. We’ll also tell you about our live, in-person workshops, and how to get one-on-one advice. You’ll be joining over 100,000 subscribers, can unsubscribe in one click, and we’ll never pass on your email.

115 | 121 | 122 |It’s only 90 minutes and covers the key ideas, in less depth.

124 | 125 |It’s available in Kindle or paperback.

127 | 128 |In our career review on medical careers, which is based on the research we mention, we provide an optimistic all considered estimate of 4 DALYs averted per year (mean). Over a 35 year career, that’s 140 DALYs averted. Individual doctors will do more or less depending on their ability and speciality.

52 |A standard conversion rate is 30 DALYs = 1 life saved.

53 |

54 | Source: World Bank, p. 402, retrieved 31-March-2016`]

55 |

56 | Using a standard conversion rate (used by the World Bank among other institutions) of 30 extra years of healthy life to one “life saved,” 140 years of healthy life is equivalent to 5 lives saved. This is clearly a significant impact, however it’s less of an impact than many people expect doctors to have.

57 |

58 | There are three main reasons for this.

59 |

60 | 1. Researchers largely agree that medicine has only increased average life expectancy by a few years. Most gains in life expectancy over the last 100 years have instead occurred due to better nutrition, improved sanitation, increased wealth, and other factors.

61 | 1. Doctors are only one part of the medical system, which also relies on nurses and hospital staff, as well as overhead and equipment. The impact of medical interventions is shared between all of these elements.

62 | 1. Most importantly, there are already a lot of doctors in the developed world, so if you don’t become a doctor, someone else will be available to perform the most critical procedures. *Additional* doctors therefore only enable us to carry out procedures that deliver less significant and less certain results.

63 |

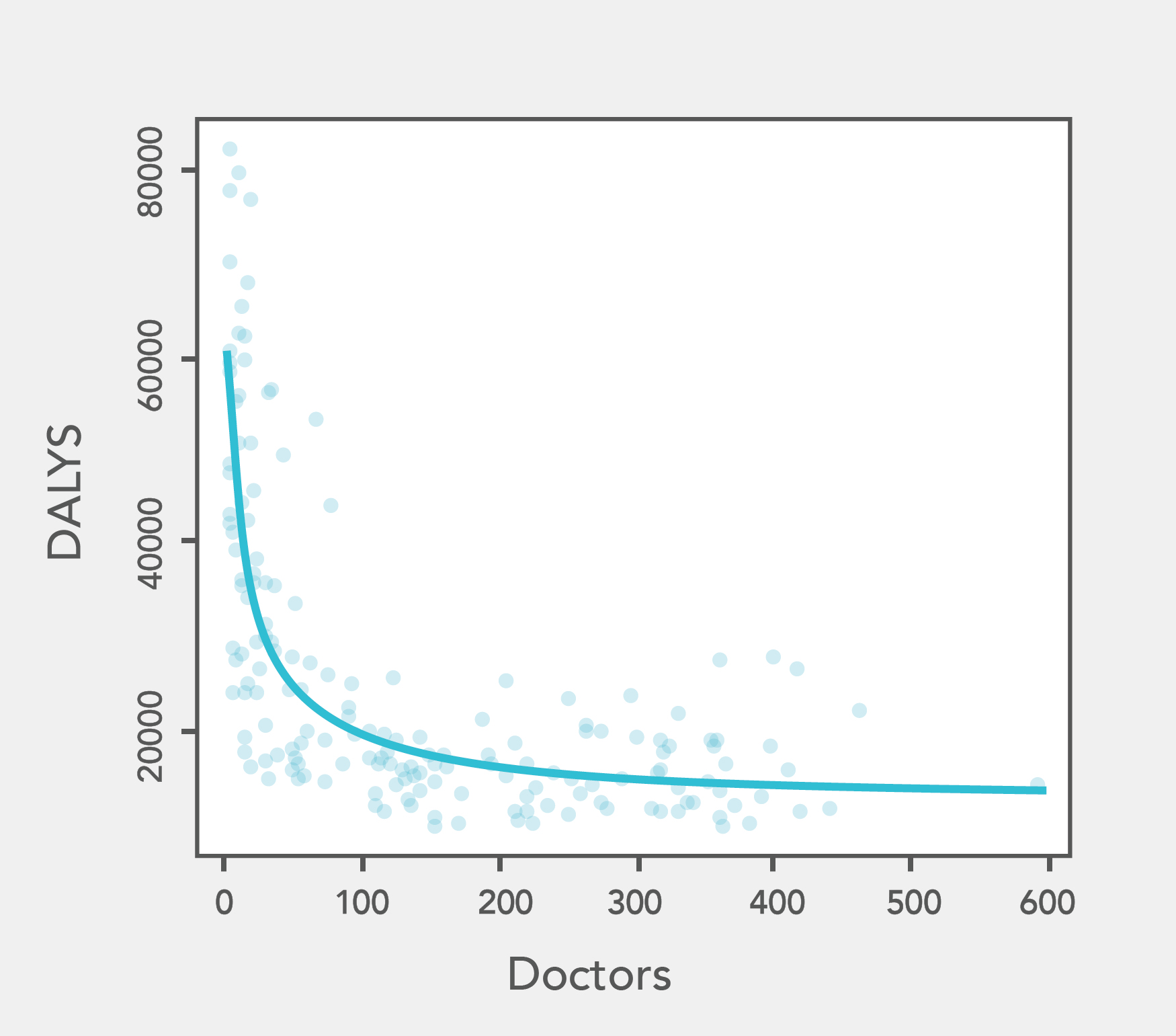

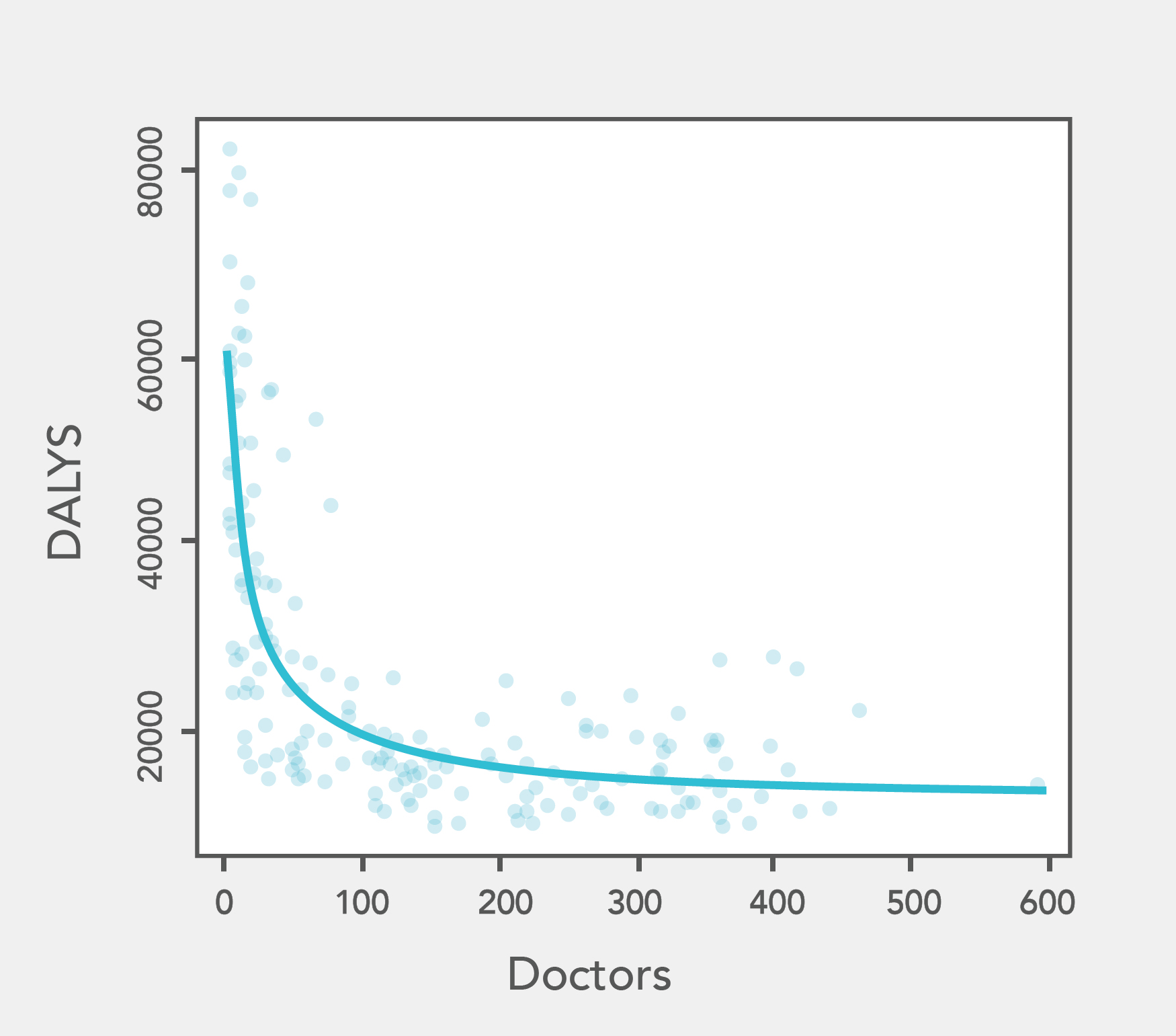

64 | This last point is illustrated by the chart below, which compares the impact of doctors in different countries. The y-axis shows the amount of ill health in the population, measured in Disability-Adjusted Life Years (aka “DALYs”) per 100,000 people, where one DALY equals one year of life lost due to ill health. The x-axis shows the number of doctors per 100,000 people.

65 |

66 | [`DALYs per 100,000 people versus doctors per 100,000 people. We used WHO data from 2004. Line is the best fitting hyperbola determined by non-linear least square regression. Full explanation in this paper.`]

67 |

68 | You can see that the curve goes nearly flat once you have more than 150 doctors per 100,000 people. After this point (which almost all developed countries meet), additional doctors only achieve a small impact on average.

69 |

70 | So if you become a doctor in a rich country like the US or UK, you may well do more good than you would in many other jobs, and if you would be an exceptional doctor, then you’ll have a bigger impact than these averages. But it probably won’t be a huge impact.

71 |

72 | In fact, in the next article, we’ll show how almost any college graduate can do more to save lives than a typical doctor. And in the guide, we’ll cover many other examples of common but ineffective attempts to do good.

73 |

74 | These findings motivated Greg to switch from clinical medicine into public health, for reasons we’ll explain over the rest of the guide.

75 |

76 | ## Who were the highest-impact people in history?

77 |

78 | Despite this uninspiring statistic about how many lives a doctor saves, some doctors have had *much* more impact than this. Let’s look at some examples of the highest-impact careers in history, and see what we might learn from them. First, let’s turn to medical research.

79 |

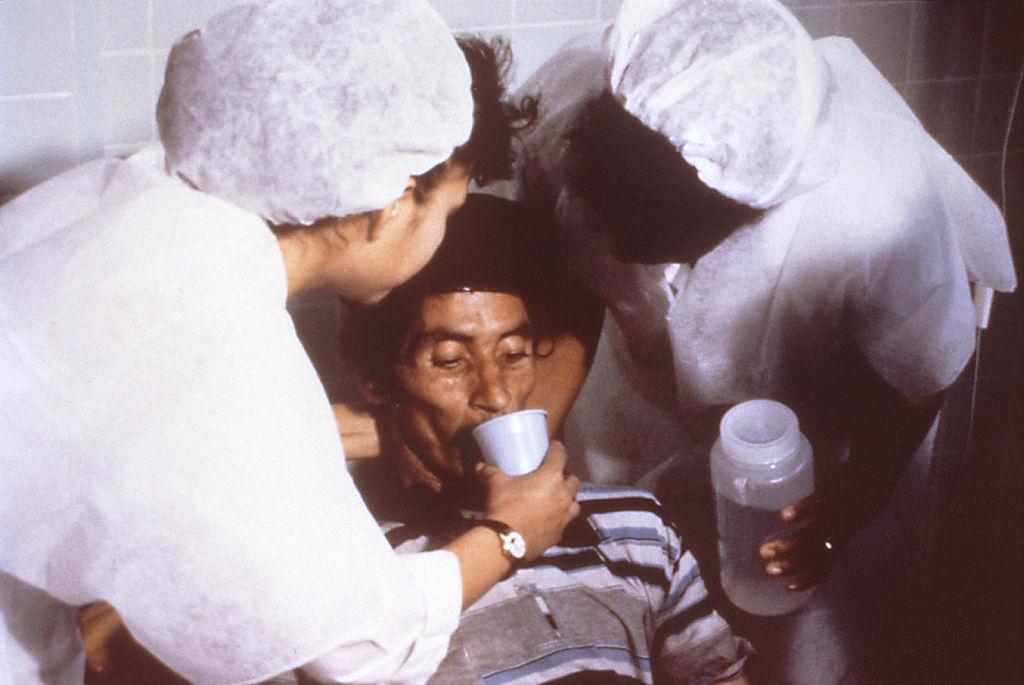

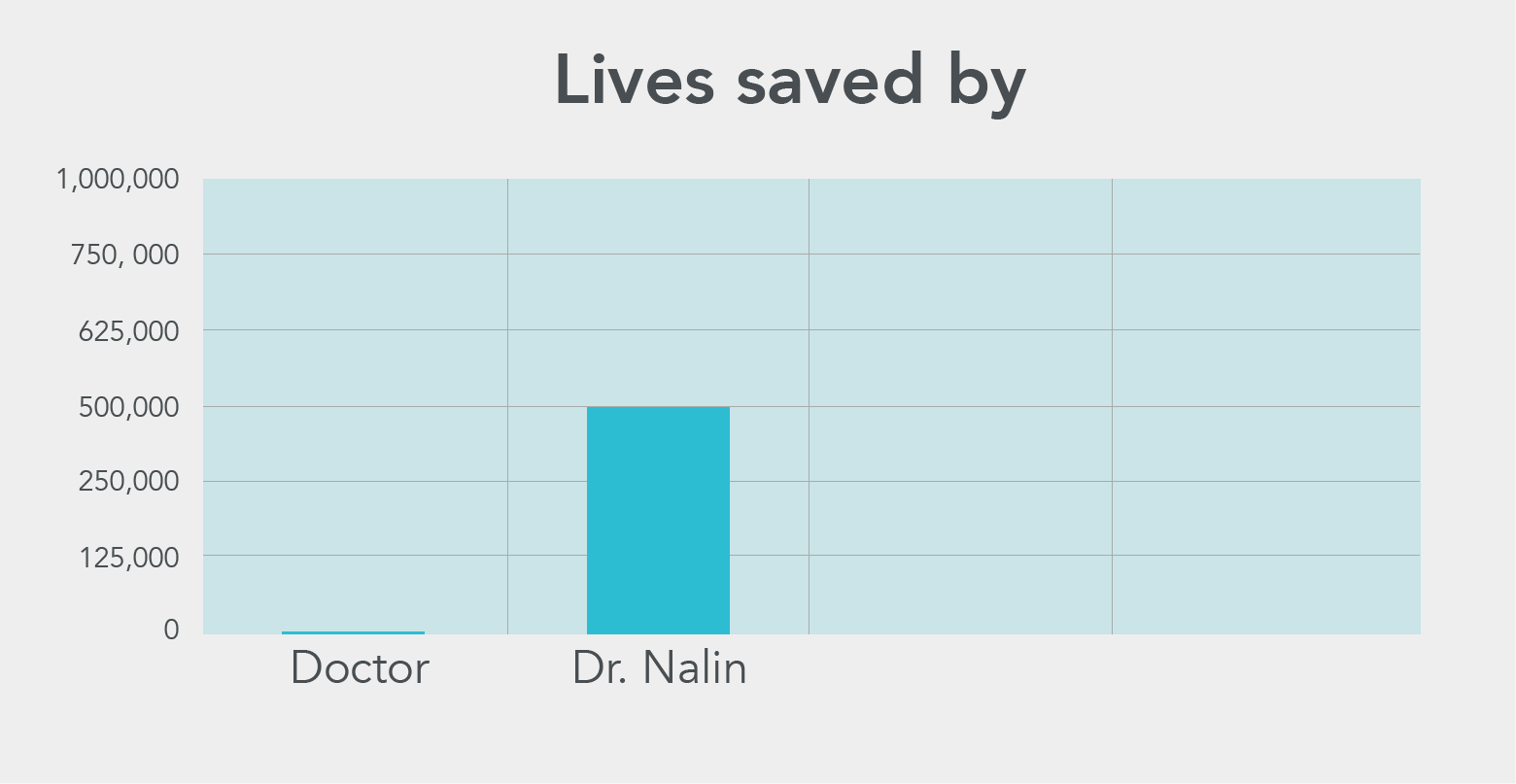

80 | In 1968, while working in a refugee camp on the border of Bangladesh and Burma, Dr. David Nalin discovered a breakthrough treatment for patients suffering from diarrhea. He realised that giving patients water mixed with the right concentration of salt and sugar would rehydrate them at the same rate at which they lost water. This prevented death from dehydration much more cheaply than did the conventional treatment of using an intravenous drip.

81 |

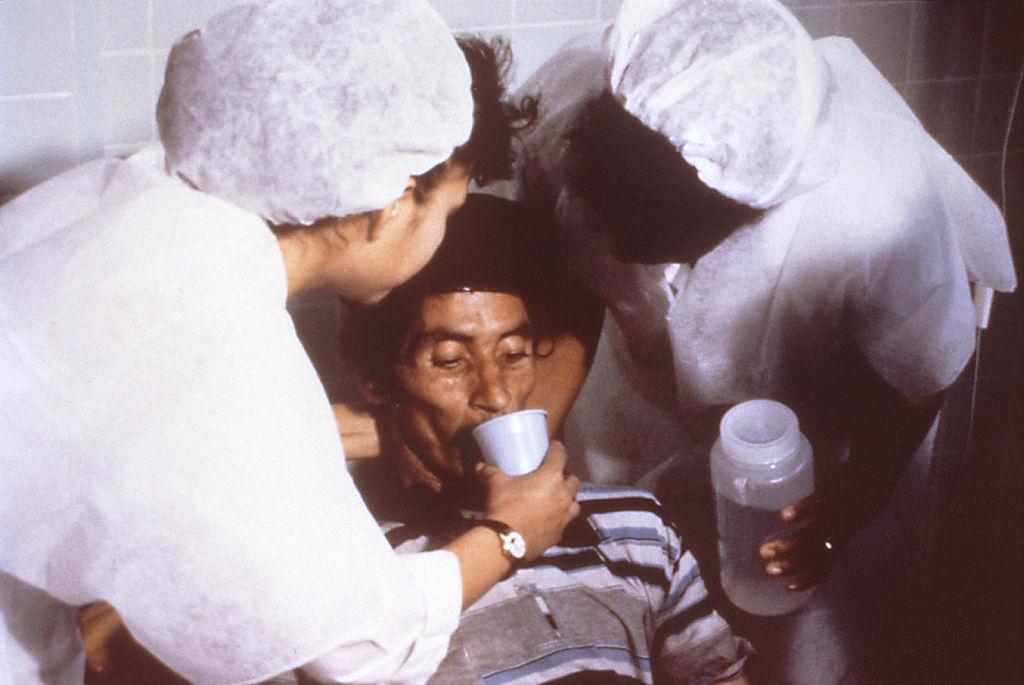

82 | [`Dr. Nalin helped to save millions of lives with a simple innovation: giving diarrhoea patients water mixed with salt and sugar.`]

83 |

84 | Since then, this astonishingly simple treatment has been used all over the world, and the annual rate of child deaths from diarrhea has plummeted from 5 million to 1.3 million. Researchers estimate that the therapy has saved about 50 million lives, mostly children’s.[^:`

87 |85 | Since the adoption of this inexpensive and easily applied intervention, the worldwide mortality rate for children with acute infectious diarrhoea has plummeted from 5 million to about 1.3 million deaths per year. Over fifty million lives have been saved in the past 40 years by the implementation of ORT. 86 |

88 | Source: Science Heroes. Archived link, retrieved 4-March-2016.

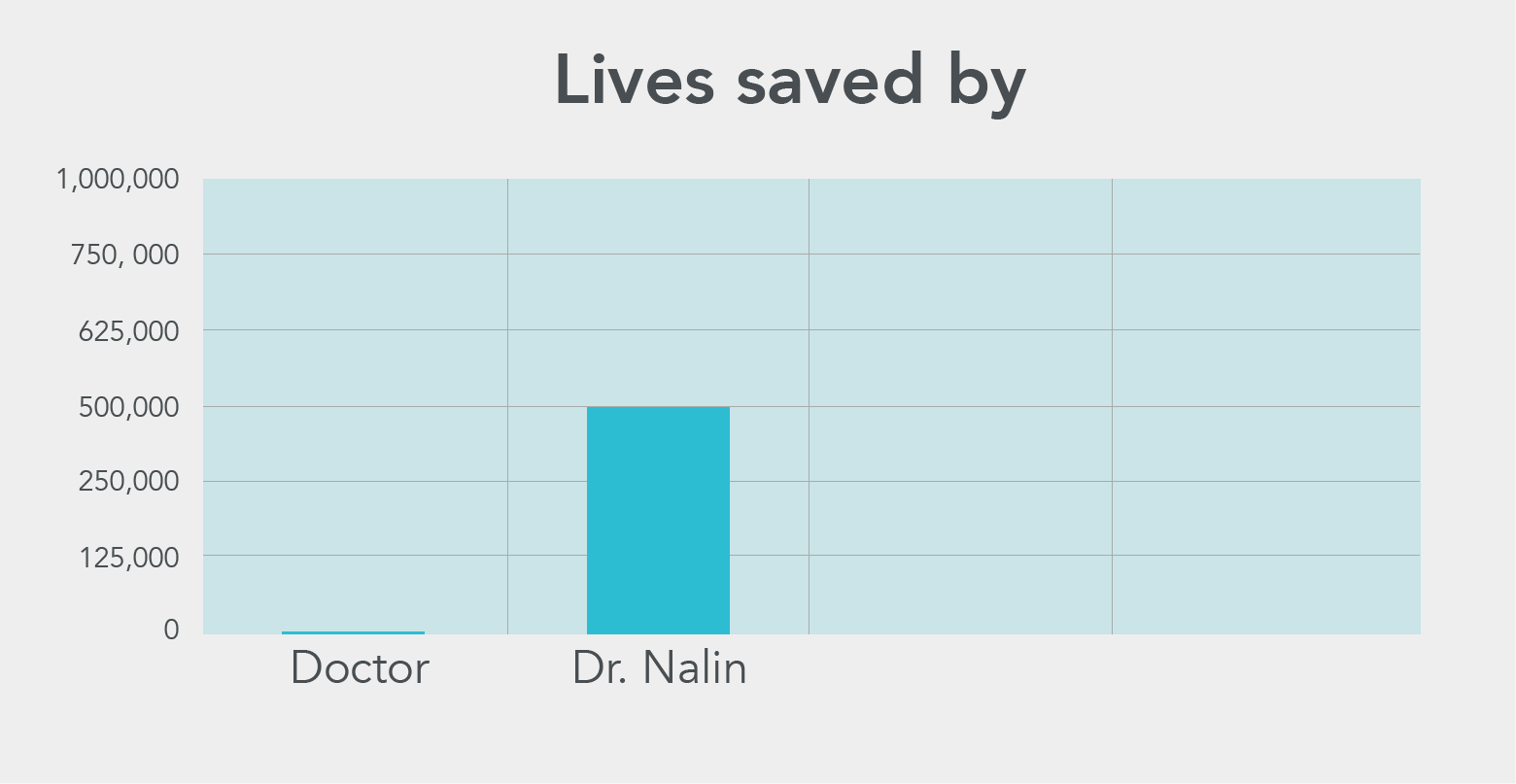

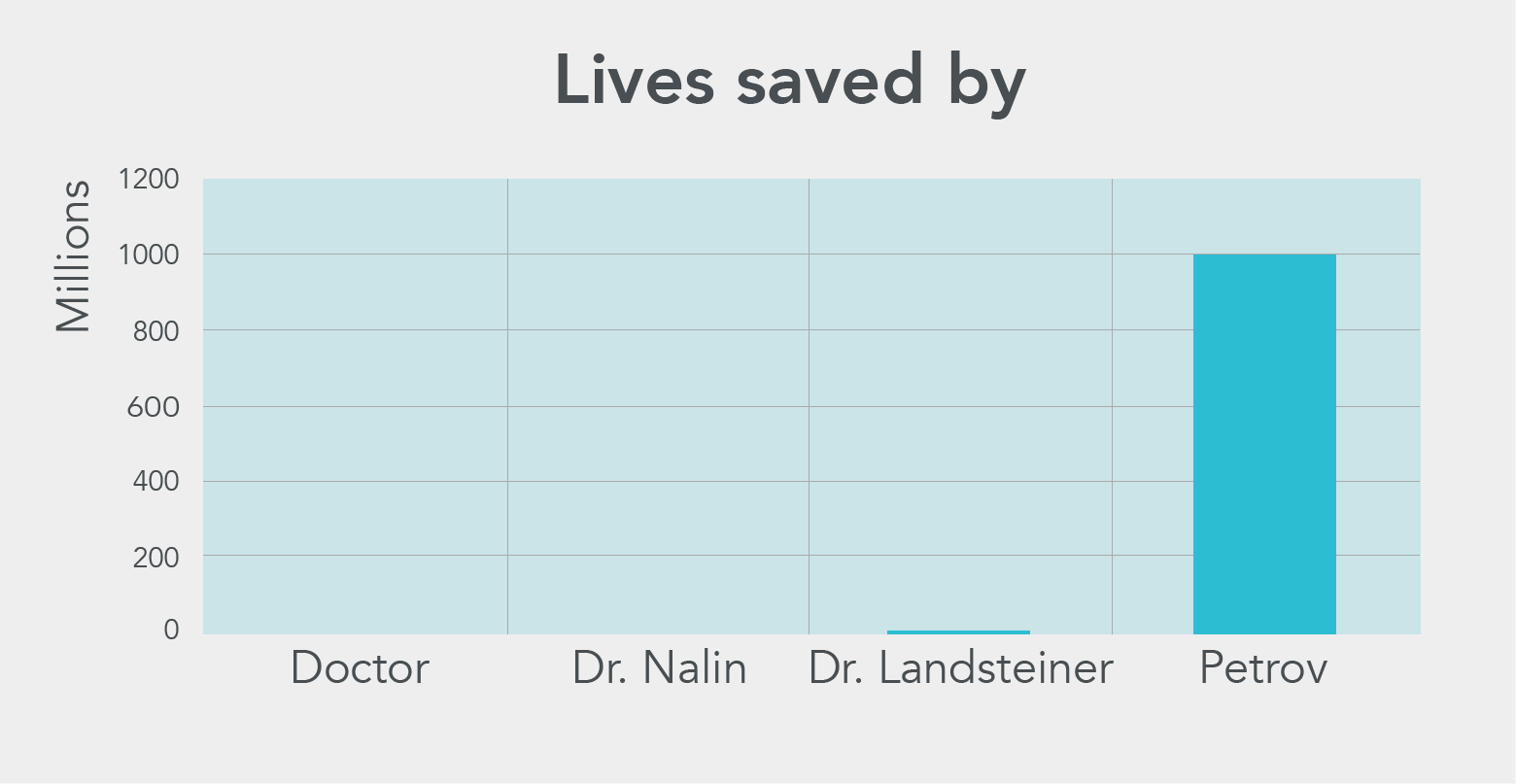

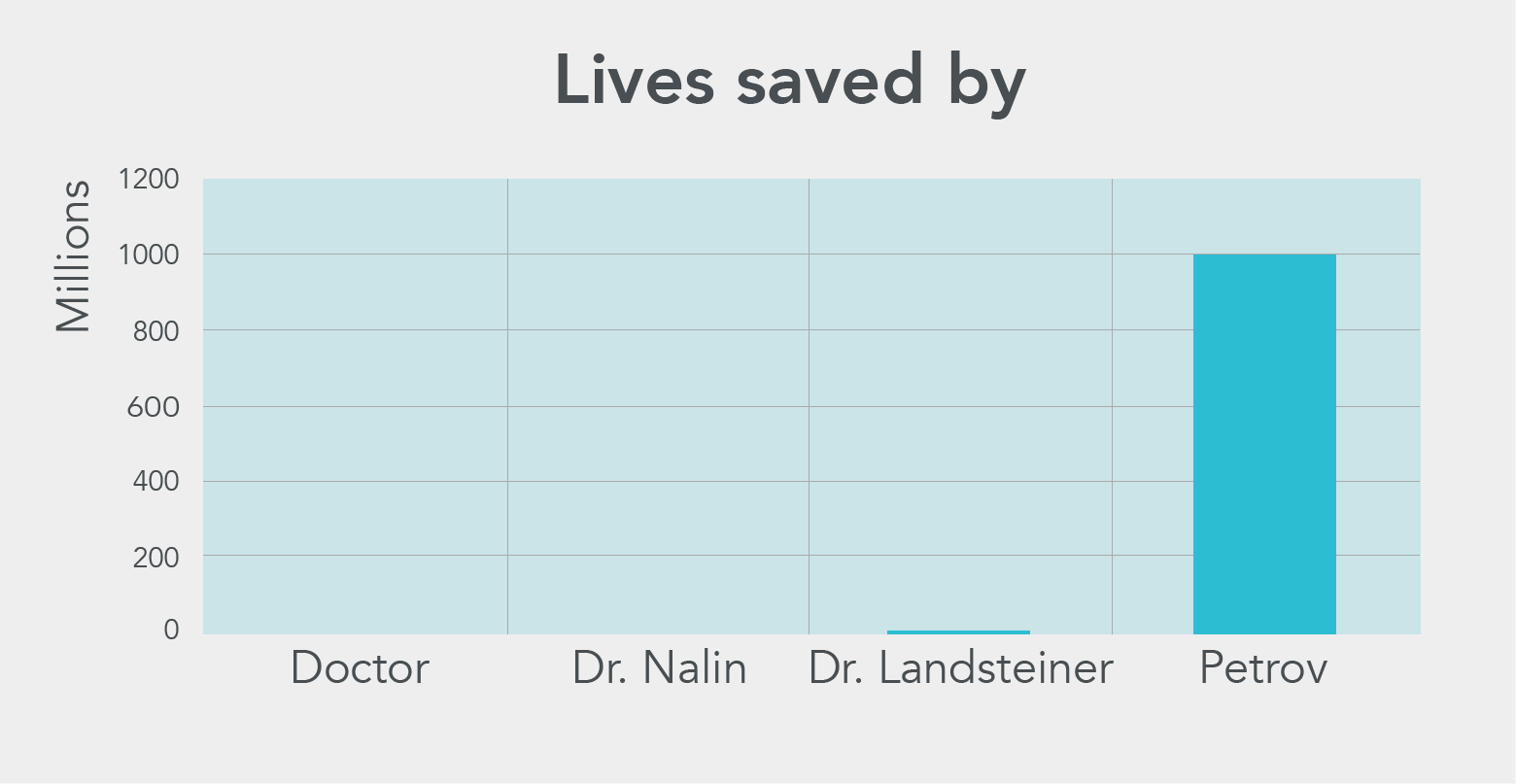

89 |Very roughly, this means 50/40 = 1.25 million lives have been saved per year. So if Dr Nalin sped up the discovery by 5 months (just a guess), that means that (5/12)*1.25 = 0.52 million extra lives were saved by his actions. This is a highly approximate estimate and could easily be off by an order of magnitude. See more comments in the next footnote.`] 90 | 91 | If Dr. Nalin had not been around, someone else would, no doubt, have discovered this treatment eventually. However, even if we imagine that he sped up the roll-out of the treatment by only five months, his work alone would have saved about 500,000 lives. This is a very approximate estimate, but it makes his impact more than 100,000 times greater than that of an ordinary doctor: 92 | 93 | [``] 94 | 95 | But even just within medical research, Dr. Nalin is far from the most extreme example of a high-impact career. For example, one estimate puts Karl Landsteiner’s discovery of blood groups as saving tens of millions of lives.[^:`

99 |96 | Superman of Science Makes Landmark Discovery - Over 1 Billion Lives Saved So Far

97 |Every source quoted an amazing number of transfusions and potential lives saved in countries and regions worldwide. High impact years began around 1955 and calculations are loosely based on 1 life saved per 2.7 units of blood transfused. In the USA alone an estimated 4.5 million lives are saved each year. From these data I determined that 1.5% of the population was saved annually by blood transfusions and I applied this percentage on population data from 1950-2008 for North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of Asia and Africa. This rate may inflate the effectiveness of transfusions in the early decades but excludes the developing world entirely. 98 |

100 | Source: Science Heroes. Archived link, retrieved 4-March-2016.

101 |If we assume a constant number of lives saved per year, then that’s about 10 million lives per year. If he sped up the discovery by two years, then that’s 20 million lives saved.

102 |This is a highly approximate estimate and could easily be off by an order of magnitude in either direction, and seem more likely to be too high than too low. We’re a bit sceptical of the Science Heroes figures. Moreover, our attempt at modelling the speed-up is very simple. Since most of the lives were saved in the modern era once a large number of people had medical care, it’s possible that speeding up the discovery wouldn’t have had much impact at all. On the other hand, the discovery of blood groups probably made other scientific advances possible, and we’re ignoring their impact. Nevertheless, the basic point stands: Landsteiner's impact was likely vastly greater than a typical doctor.`] 103 | 104 | [``] 105 | 106 | Leaving the medical field, later in the guide, we’ll cover the story of a hugely impactful mathematician, Alan Turing, and bureaucrat, Viktor Zhdanov. 107 | 108 | Or, let’s think even more broadly. Roger Bacon and Galileo pioneered the scientific method, without which none of the discoveries we covered above would have been possible, along with other major technological breakthroughs like the Industrial Revolution. These individuals were able to do vastly more good than even outstanding medical practitioners. 109 | 110 | ### The unknown Soviet Lieutenant Colonel who saved your life 111 | 112 | [``] 113 | 114 | Or consider the story of Stanislav Petrov, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Soviet army during the Cold War. In 1983, Petrov was on duty in a Soviet missile base when early warning systems apparently detected an incoming missile strike from the United States. Protocol dictated that the Soviets order a return strike. 115 | 116 | But Petrov didn’t push the button. He reasoned that the number of missiles was too small to warrant a counterattack, thereby disobeying protocol. 117 | 118 | If he had ordered a strike, there’s at least a reasonable chance hundreds of millions would have died. The two countries may have even ended up engaged in an all-out nuclear war, leading to billions of deaths and, potentially, the end of civilisation. If we’re being conservative, we might quantify his impact by saying he saved one billion lives. But that could be an underestimate, because a nuclear war would also have devastated scientific, artistic, economic and all other forms of progress leading to a huge loss of life and well-being over the long run. Yet even with the lower estimate, Petrov’s impact likely dwarfs that of Nalin and Landsteiner. 119 | 120 | [``] 121 | 122 | ## What does this spread in impact mean for your career? 123 | 124 | We’ve seen that some careers have had huge positive effects, and some have vastly more than others. 125 | 126 | Some component of this is due to luck – the people mentioned above were in the right place at the right time, affording them the opportunity to have an impact that they might not have otherwise received. You can’t guarantee you’ll make an important medical discovery. 127 | 128 | But it wasn’t all luck: Landsteiner and Nalin chose to use their medical knowledge to solve some of the most harmful health problems of their day, and it was foreseeable that someone high up in the Soviet military could have a large impact by preventing conflict during the Cold War. So, what does this mean for you? 129 | 130 | People often wonder how they can “make a difference”, but if some careers can result in thousands of times more impact than others, this isn’t the right question. Two career options can both “make a difference”, but one could be dramatically better than the other. 131 | 132 | Instead, the key question is, “how can I make the most difference?” In other words: what can you do to give yourself a chance of having one of the highest-impact careers? Because the highest-impact careers achieve so much, a small increase in your chances means a great deal. 133 | 134 | The examples above also show that the highest-impact paths might not be the most obvious ones. Being an officer in the Soviet military doesn’t sound like the best career for a would-be altruist, but Petrov probably did more good than our most celebrated leaders, not to mention our most talented doctors. Having a big impact might require doing something a little unconventional. 135 | 136 | So how much impact can *you* have if you try, while still doing something personally rewarding? It’s not easy to have a big impact, but there’s a lot you can do to increase your chances. That’s what we’ll cover in the next couple of articles. 137 | 138 | But first, let’s clarify what we mean by “making a difference”. We’ve been talking about lives saved so far, but that’s not the only way to do good in the world. 139 | 140 | ## What does it mean to “make a difference?” 141 | 142 | Everyone talks about “making a difference” or “changing the world” or “doing good” or “impact”, but few ever define what they mean. 143 | 144 | So here’s our definition. Your social impact is given by: 145 | 146 | > The number of people whose lives you improve, and how much you improve them. 147 | 148 | This means you can increase your social impact in two ways: by helping more people, or by helping the same number of people to a greater extent (pictured below). 149 | 150 |  151 | 152 | We also include the lives you improve in the future, so you can also increase your impact by helping in ways that have long-term benefits. For example, if you improve the quality of government decision-making, you might not see many quantifiable short-term results, but you will have solved lots of other problems over the long-run. 153 | 154 | ``` 155 |

Many people disagree about what it means to make the world a better place. But most agree that it’s good if people have happier, more fulfilled lives, in which they reach their potential. So, our definition is narrow enough that it captures this idea. 158 |

Moreover, as we’ll show, some careers do far more to improve lives than others, so it captures a really important difference between options. If some paths can do good equivalent to saving hundreds of lives, while others have little impact at all, that’s an important difference. 159 |

But, the definition is also broad enough to cover many different ways to make the world a better place. It’s even broad enough to cover environmental protection, since if we let the environment degrade, the future of civilisation might be threatened. In that way, protecting the environment improves lives. 160 |

Many of our readers also expand the scope of their concern to include non-human animals, which is one reason why we did a profile on factory farming. 161 |

That said, the definition doesn’t include *everything* that might matter. You might think the environment deserves protection even if it doesn’t make people better off. Similarly, you might value things like justice and aesthetic beauty for their own sake. 162 |

In practice, our readers value many different things. Our approach is to focus on how to improve lives, and then let people independently take account of what else they value. To make this easier, we try to highlight the main value judgments behind our work. It turns out there’s a lot we can say about how to do good in general, despite all these differences. 163 |

We are always uncertain about how much impact different actions will have, but that’s okay, because we can use probabilities to make the comparison. For instance, a 90% chance of helping 100 people is roughly equivalent to a 100% chance of helping 90 people. Though we’re uncertain, we can quantify our uncertainty and make progress. 165 |

Moreover, we can still use rules of thumb to compare different courses of action. For instance, in an upcoming article we argue that, all else equal, it’s higher-impact to work on neglected areas. So, even if we can’t precisely *measure* social impact, we can still be *strategic* by picking neglected areas. We’ll cover many more rules of thumb for increasing your impact in the upcoming articles. 166 |

(Read more about the definition of social impact.) 167 |

Continue → 178 |

If you’re new, go to the start of the guide. 179 |

No time right now? Join our newsletter and we’ll send you one article each week. 180 |

The most pressing problems are likely to have a good combination of the following qualities:

61 |To find the problem you should work on, also consider, personal fit. Could you become motivated to work on this problem? If you’re later in your career, do you have relevant expertise?

67 |See how we applied the framework in the next article.

68 |The average British person uses about 120 kWh per day.

84 |Source: Figure 1.12, Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air, by David MacKay, 2008, archived link, retrieved 14-April-2017.

85 |Heating an un-insulated detached home takes about 53 kWh per day, while adding loft and wall insulation reduces that by 44% to 30 kWh/d. Assuming a single house contains 2.5 people, then compared to total energy use per person, that's a reduction of 33/(1202.5) = 11%. If unplugging phone chargers when they're not in use reduces personal energy use by under 0.01%, then adding home insulation is 1100 times more important. It can also cut your heating bill by 44%, which can mean you save money over the long-term, depending on the cost of the insulation.

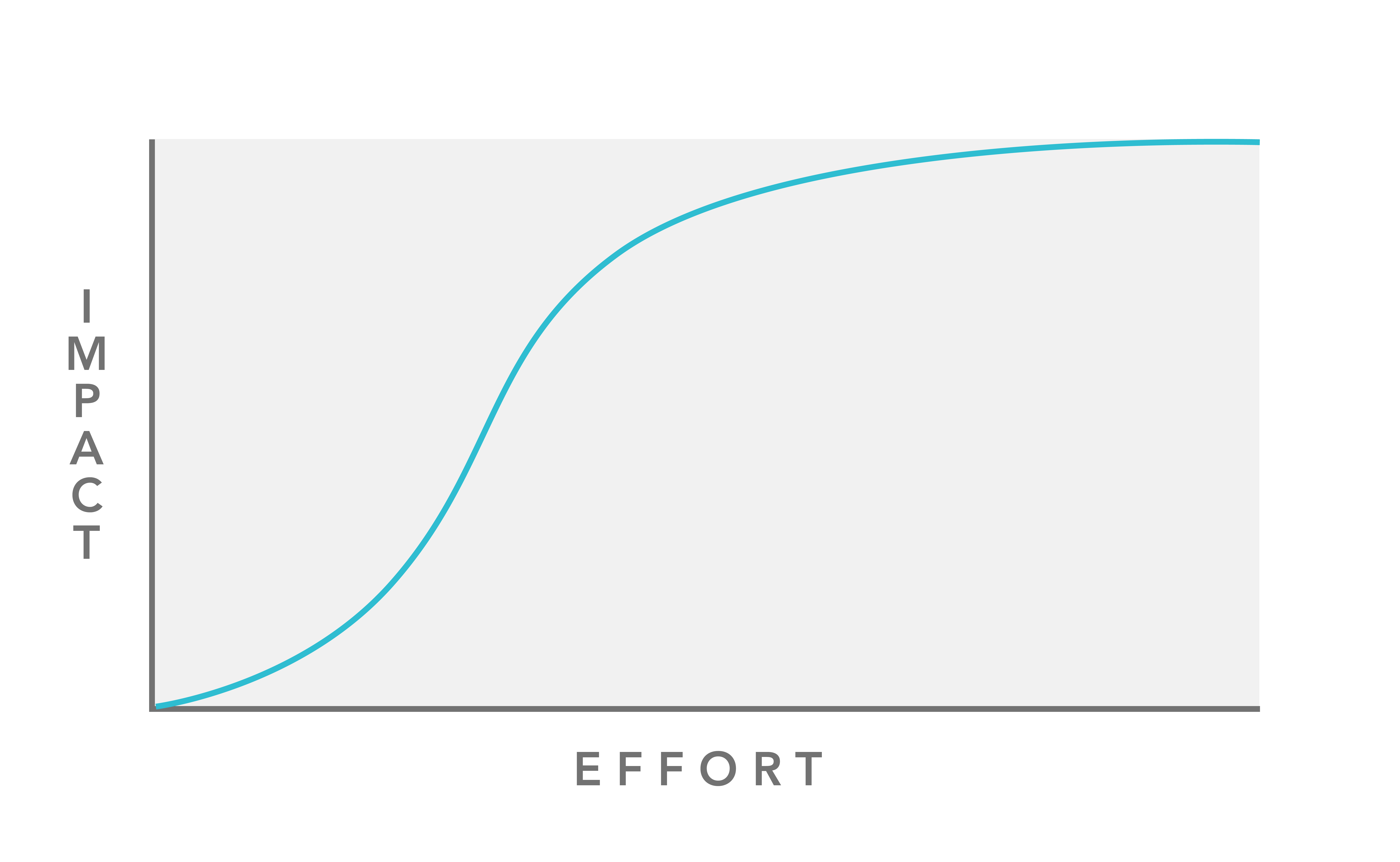

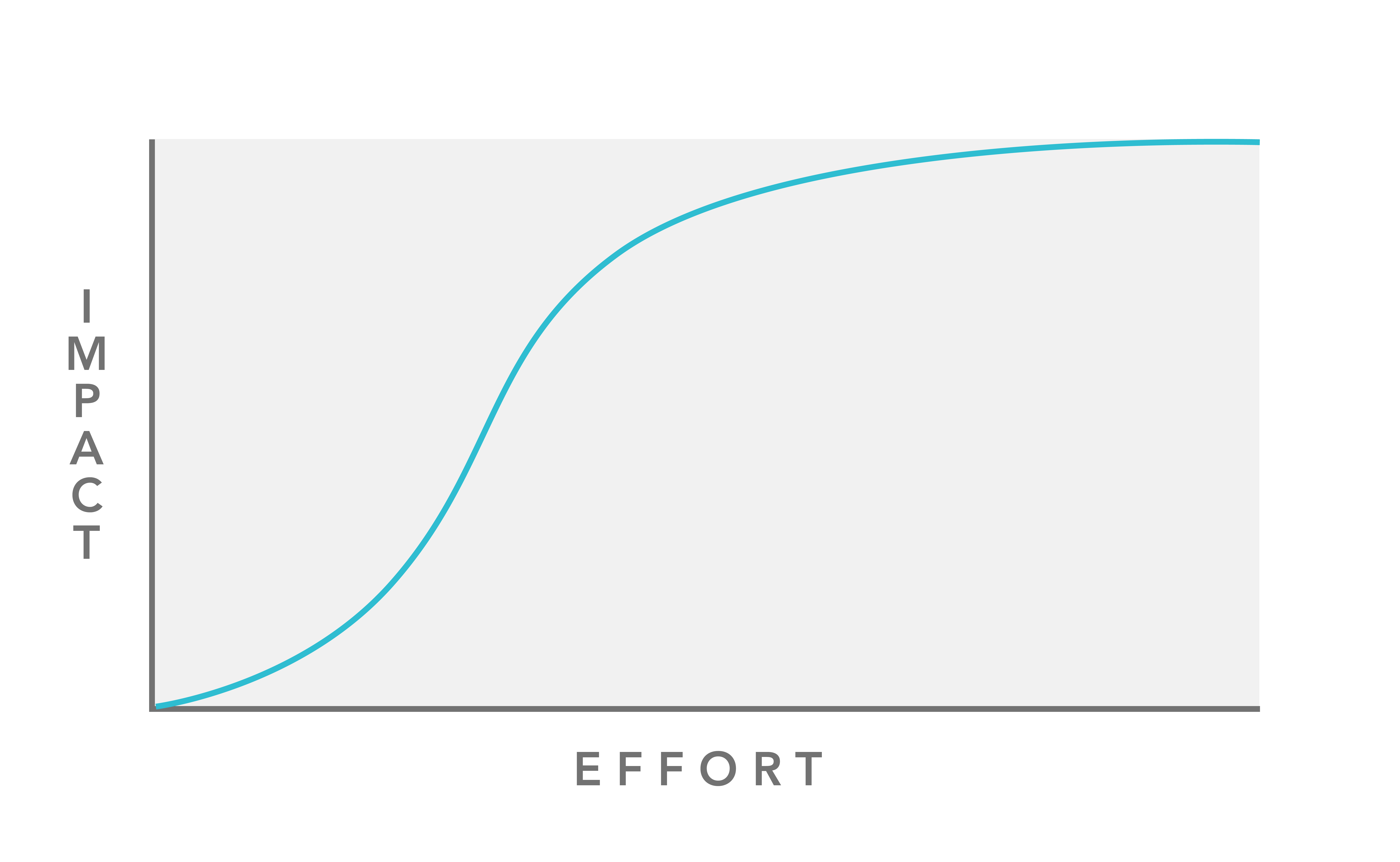

86 |Source: Figure 21.3, *Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air, by David MacKay, 2008, archived link, retrieved 14-April-2017.`] 87 | 88 | Decades of research has shown that our intuition is bad at assessing differences in scale. For instance, one study found that people were willing to pay about the same amount to save 2,000 birds from oil spills as they were to save 200,000 birds, even though the latter is objectively one hundred times better. This is an example of a common error called scope neglect. 89 | 90 | Rather, we need to use numbers to make comparisons, even if they’re very rough. 91 | 92 | In the previous article, we said that social impact depends on the extent to which you help others live better lives. So based on this definition, a problem has greater scale: 93 | 94 | 1. The larger the number of people affected 95 | 1. The larger the size of the effects per person and, 96 | 1. The larger the long-run benefits of solving the problem. 97 | 98 | Scale is important because the effect of activities on a problem is often proportional to the size of the problem. Launch a campaign that ends 10% of the phone charger problem, and you achieve very little. Launch a campaign that persuades 10% of people to install home insulation, and it’s a much bigger deal. 99 | 100 | [`If we cared so little about the relative importance of different problems in our personal lives.`] 101 | 102 | ## 2. Work on a problem that’s neglected 103 | 104 | In the previous article, we saw that medicine in the US and UK is a relatively crowded problem – there are already over 700,000 doctors in the US and health spending is high, which makes it harder for an extra person working on health to make a big contribution.[^:`

Studies find that the United States has about 230 doctors per 100,000 people. With a population of approximately 320 million, that means there are over 700,000 doctors in the United States.

105 |“An analysis by Schieber et al. (1993) of the health care delivery systems of the late 1980s and early 1990s in the 24 industrialized countries that constituted the membership of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) revealed a physician supply ranging from 90 per 100,000 population (Turkey) to 380 (Spain). The U.S. supply was 230 per 100,000 persons at that time, a figure close to the OECD average of 240. Again, the United States was found to have a much higher specialist-to-generalist ratio than the other OECD nations. The authors concluded that these differences in specialty mix tempered the utility of the comparisons.”

106 |Archived link, retrieved 11 March 2016.`] 107 | 108 | Health in poor countries, however, receives much less attention, and that’s one reason why it’s possible to save a life for only about $7,500. 109 | 110 | The more effort that’s already going into a problem, the harder it is for *you* to be successful and make a meaningful contribution. This is due to *diminishing returns*. 111 | 112 | When you pick fruit from a tree, you start with those that are easiest to reach – the low hanging fruit. When they’re gone, it becomes harder and harder to get a meal. 113 | 114 | It’s the same with social impact. When few people have worked on a problem, there are generally lots of great opportunities to make progress. As more and more work is done, it becomes harder and harder to be original and have a big impact. It looks a bit like this: 115 | 116 | [`Diminishing returns to effort – it’s economics 101.`] 117 | 118 | The problems your friends are talking about and that you see in the news are where everyone else is already focused. So, they’re not the neglected problems, and probably not the most urgent. 119 | 120 | Rather, the most urgent problems – those where you have the greatest impact – are probably areas you’ve never thought about working on. 121 | 122 | We all know about the fight against cancer, but what about parasitic worms? It doesn’t make for such a good charity music video, but these tiny creatures have infected one billion people worldwide with neglected tropical diseases.[^:`

“Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) are a group of parasitic and bacterial diseases that cause substantial illness for more than one billion people globally. Affecting the world's poorest people, NTDs impair physical and cognitive development, contribute to mother and child illness and death, make it difficult to farm or earn a living, and limit productivity in the workplace. As a result, NTDs trap the poor in a cycle of poverty and disease.”

123 |Archived link, retrieved 11 March 2016.`] These conditions are far easier to treat than cancer, but we never even hear about them because they very rarely affect rich people.

124 |

125 | So instead of following the trend, seek out problems that other people are systematically missing. For instance:

126 |

127 | 1. Does the problem affect neglected groups, like those a long way away, animals, or our grandchildren rather than us?

128 | 1. Is the problem a low probability event, which might be getting overlooked?

129 | 1. Do few people know about the problem?

130 |

131 | Following this advice is harder than it looks, because it means standing out from the crowd, and that might mean looking a little weird.

132 |

133 | [`Okay, that *is* a neglected problem, but neglectedness is not the only thing you need to look for.

`]

134 |

135 | ## 3. Work on problems that are solvable

136 |

137 | Lots of charitable programmes don’t work. Here’s an example in the field of reducing youth crime.

138 |

139 | Scared Straight is a programme that takes kids who have committed misdemeanours to visit prisons and meet convicted criminals, confronting them with their likely future if they don’t change their ways. The concept proved popular not just as a social programme but as entertainment; it was adapted for both an acclaimed documentary and a TV show on A&E, which broke ratings records for the network upon its premiere.

140 |

141 | There’s just one problem with Scared Straight: it probably causes young people to commit more crimes.

142 |

143 | Or more precisely, the young people who went through the programme *did* commit fewer crimes than they did before, so superficially it looked like it worked. But the decrease was smaller compared to similar young people who never went through the programme.

144 |

145 | The effect is so significant that the Washington State Institute for Public Policy estimated that each $1 spent on Scared Straight programmes causes more than $200 worth of social harm.[^:`

A meta-analysis by the Campbell Collaboration, a leading evaluator of the effectiveness of social policies, concluded:

146 |152 |147 | RESULTS

149 |

148 | The analyses show the intervention to be more harmful than doing nothing. The program effect, whether assuming a fixed or random effects model, was nearly identical and negative in direction, regardless of the meta-analytic strategy.AUTHOR’S CONCLUSIONS

150 | We conclude that programs like ‘Scared Straight’ are likely to have a harmful effect and increase delinquency relative to doing nothing at all to the same youths. Given these results, we cannot recommend this program as a crime prevention strategy. Agencies that permit such programs, however, must rigorously evaluate them not only to ensure that they are doing what they purport to do (prevent crime) – but at the very least they do not cause more harm than good to the very citizens they pledge to protect. 151 |

Link, Archived PDF of full report, retrieved 27-April-2017.

153 |A review of American social programmes made a cost-benefit analysis of the programme, concluding there were $203 social costs incurred per $1 invested in the programme. See Table 1. However, note that this estimate is quite old so could be out-of-date. Moreover, we're generally sceptical of very large differences between costs and benefits, so we doubt the true ratio is as high as this. Nevertheless, the programme looks to have been a terrible use of resources.

154 |Archived link, retrieved 31 March 2016.`] This estimate seems a little too pessimistic to us, but even so, it looks like it was a huge mistake. 155 | 156 | No-one is sure why this is, but it might be because the young people realised that life in jail wasn’t as bad as they thought, or they came to admire the criminals. 157 | 158 | Some attempts to do good, like Scared Straight, make things worse. Many more fail to have an impact. David Anderson of the Coalition for Evidence Based Policy estimates: 159 | 160 | > Of [social programmes] that have been rigorously evaluated, most (perhaps 75% or more), including those backed by expert opinion and less-rigorous studies, turn out to produce small or no effects, and, in some cases negative effects. 161 | 162 | This suggests that if you chose a charity to get involved in without looking at the evidence, you’ll most likely *have no impact at all*. 163 | 164 | Worse, it’s very hard to tell which programmes are going to be effective ahead of time. Don’t believe us? Try our 10 question quiz, and see if you can guess what’s effective: 165 | 166 | Play the game 167 | 168 | The quiz asks you to guess which social interventions work and which don’t. We’ve tested it on hundreds of people, and they hardly do better than chance. 169 | 170 | So, before you choose a social problem, ask yourself: 171 | 172 | 1. Is there a way to make progress on this problem with rigorous evidence behind it? For instance, lots of studies have shown that malaria nets prevent malaria. 173 | 1. Is this an attempt to try out a new but promising programme, to test whether it works? 174 | 1. Is this a programme with a small but realistic chance of making a massive impact? For instance, research into a key question, or a political campaign. 175 | 176 | If the answer to all of these is no, then it’s probably best to find something else. 177 | 178 | (Read more about whether it’s fair to say most social programmes don’t work.) 179 | 180 | [`Scared Straight showed juvenile delinquents life inside jail, aiming to scare them away from crime. The only catch: it made them more likely to commit crimes rather than less.`] 181 | 182 | ## Look for the best balance of the factors 183 | 184 | You probably won’t find something that does brilliantly on all three dimensions. Rather, look for what does best on balance. A problem could be worth tackling if it’s extremely big and neglected, even if it seems hard to solve. 185 | 186 | *To get the full details on the framework set out here, see this in-depth article, which also tells you how to make your own comparisons of areas.* 187 | 188 | ## Your personal fit and expertise 189 | 190 | There’s no point working on a problem if you can’t find any roles that are a good fit for you – you won’t be satisfied or have much impact. 191 | 192 | So, once you’ve identified problems that have a good combination of being big, neglected and solvable: 193 | 194 | 1. Consider all the roles you could take to contribute to them. We cover this in a later article. 195 | 1. Narrow those down based on where you expect to be most successful. We’ll discuss how to assess personal fit in a later article. 196 | 197 | If you’re already an expert in a problem, then it’s probably best to work within your area of expertise. It wouldn’t make sense for, say, an economist who’s crushing it to switch into something totally different. However, you could still use the framework to narrow down sub-fields e.g. development economics vs. employment policy. 198 | 199 | ## So what's the world's most urgent problem? 200 | 201 | What are the biggest problems in the world that no-one is talking about and are possible to solve? That’s what we’ll cover next. 202 | 203 | ``` 204 |

If you’re new, go to the start of the guide.

208 |No time now? Join our newsletter and we’ll send you one article each week.

209 |The most pressing problems are likely to have a good combination of the following qualities:

61 |To find the problem you should work on, also consider, personal fit. Could you become motivated to work on this problem? If you’re later in your career, do you have relevant expertise?

67 |See how we applied the framework in the next article.

68 |The average British person uses about 120 kWh per day.

84 |Source: Figure 1.12, Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air, by David MacKay, 2008, archived link, retrieved 14-April-2017.

85 |Heating an un-insulated detached home takes about 53 kWh per day, while adding loft and wall insulation reduces that by 44% to 30 kWh/d. Assuming a single house contains 2.5 people, then compared to total energy use per person, that's a reduction of 33/(1202.5) = 11%. If unplugging phone chargers when they're not in use reduces personal energy use by under 0.01%, then adding home insulation is 1100 times more important. It can also cut your heating bill by 44%, which can mean you save money over the long-term, depending on the cost of the insulation.

86 |Source: Figure 21.3, *Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air, by David MacKay, 2008, archived link, retrieved 14-April-2017.`] 87 | 88 | Decades of research has shown that our intuition is bad at assessing differences in scale. For instance, one study found that people were willing to pay about the same amount to save 2,000 birds from oil spills as they were to save 200,000 birds, even though the latter is objectively one hundred times better. This is an example of a common error called scope neglect. 89 | 90 | Rather, we need to use numbers to make comparisons, even if they’re very rough. 91 | 92 | In the previous article, we said that social impact depends on the extent to which you help others live better lives. So based on this definition, a problem has greater scale: 93 | 94 | 1. The larger the number of people affected 95 | 1. The larger the size of the effects per person and, 96 | 1. The larger the long-run benefits of solving the problem. 97 | 98 | Scale is important because the effect of activities on a problem is often proportional to the size of the problem. Launch a campaign that ends 10% of the phone charger problem, and you achieve very little. Launch a campaign that persuades 10% of people to install home insulation, and it’s a much bigger deal. 99 | 100 | [`If we cared so little about the relative importance of different problems in our personal lives.`] 101 | 102 | ## 2. Work on a problem that’s neglected 103 | 104 | In the previous article, we saw that medicine in the US and UK is a relatively crowded problem – there are already over 700,000 doctors in the US and health spending is high, which makes it harder for an extra person working on health to make a big contribution.[^:`

Studies find that the United States has about 230 doctors per 100,000 people. With a population of approximately 320 million, that means there are over 700,000 doctors in the United States.

105 |“An analysis by Schieber et al. (1993) of the health care delivery systems of the late 1980s and early 1990s in the 24 industrialized countries that constituted the membership of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) revealed a physician supply ranging from 90 per 100,000 population (Turkey) to 380 (Spain). The U.S. supply was 230 per 100,000 persons at that time, a figure close to the OECD average of 240. Again, the United States was found to have a much higher specialist-to-generalist ratio than the other OECD nations. The authors concluded that these differences in specialty mix tempered the utility of the comparisons.”

106 |Archived link, retrieved 11 March 2016.`] 107 | 108 | Health in poor countries, however, receives much less attention, and that’s one reason why it’s possible to save a life for only about $7,500. 109 | 110 | The more effort that’s already going into a problem, the harder it is for *you* to be successful and make a meaningful contribution. This is due to *diminishing returns*. 111 | 112 | When you pick fruit from a tree, you start with those that are easiest to reach – the low hanging fruit. When they’re gone, it becomes harder and harder to get a meal. 113 | 114 | It’s the same with social impact. When few people have worked on a problem, there are generally lots of great opportunities to make progress. As more and more work is done, it becomes harder and harder to be original and have a big impact. It looks a bit like this: 115 | 116 | [`Diminishing returns to effort – it’s economics 101.`] 117 | 118 | The problems your friends are talking about and that you see in the news are where everyone else is already focused. So, they’re not the neglected problems, and probably not the most urgent. 119 | 120 | Rather, the most urgent problems – those where you have the greatest impact – are probably areas you’ve never thought about working on. 121 | 122 | We all know about the fight against cancer, but what about parasitic worms? It doesn’t make for such a good charity music video, but these tiny creatures have infected one billion people worldwide with neglected tropical diseases.[^:`

“Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) are a group of parasitic and bacterial diseases that cause substantial illness for more than one billion people globally. Affecting the world's poorest people, NTDs impair physical and cognitive development, contribute to mother and child illness and death, make it difficult to farm or earn a living, and limit productivity in the workplace. As a result, NTDs trap the poor in a cycle of poverty and disease.”

123 |Archived link, retrieved 11 March 2016.`] These conditions are far easier to treat than cancer, but we never even hear about them because they very rarely affect rich people.

124 |

125 | So instead of following the trend, seek out problems that other people are systematically missing. For instance:

126 |

127 | 1. Does the problem affect neglected groups, like those a long way away, animals, or our grandchildren rather than us?

128 | 1. Is the problem a low probability event, which might be getting overlooked?

129 | 1. Do few people know about the problem?

130 |

131 | Following this advice is harder than it looks, because it means standing out from the crowd, and that might mean looking a little weird.

132 |

133 | [`Okay, that *is* a neglected problem, but neglectedness is not the only thing you need to look for.

`]

134 |

135 | ## 3. Work on problems that are solvable

136 |

137 | Lots of charitable programmes don’t work. Here’s an example in the field of reducing youth crime.

138 |

139 | Scared Straight is a programme that takes kids who have committed misdemeanours to visit prisons and meet convicted criminals, confronting them with their likely future if they don’t change their ways. The concept proved popular not just as a social programme but as entertainment; it was adapted for both an acclaimed documentary and a TV show on A&E, which broke ratings records for the network upon its premiere.

140 |

141 | There’s just one problem with Scared Straight: it probably causes young people to commit more crimes.

142 |

143 | Or more precisely, the young people who went through the programme *did* commit fewer crimes than they did before, so superficially it looked like it worked. But the decrease was smaller compared to similar young people who never went through the programme.

144 |

145 | The effect is so significant that the Washington State Institute for Public Policy estimated that each $1 spent on Scared Straight programmes causes more than $200 worth of social harm.[^:`

A meta-analysis by the Campbell Collaboration, a leading evaluator of the effectiveness of social policies, concluded:

146 |152 |147 | RESULTS

149 |

148 | The analyses show the intervention to be more harmful than doing nothing. The program effect, whether assuming a fixed or random effects model, was nearly identical and negative in direction, regardless of the meta-analytic strategy.AUTHOR’S CONCLUSIONS

150 | We conclude that programs like ‘Scared Straight’ are likely to have a harmful effect and increase delinquency relative to doing nothing at all to the same youths. Given these results, we cannot recommend this program as a crime prevention strategy. Agencies that permit such programs, however, must rigorously evaluate them not only to ensure that they are doing what they purport to do (prevent crime) – but at the very least they do not cause more harm than good to the very citizens they pledge to protect. 151 |

Link, Archived PDF of full report, retrieved 27-April-2017.

153 |A review of American social programmes made a cost-benefit analysis of the programme, concluding there were $203 social costs incurred per $1 invested in the programme. See Table 1. However, note that this estimate is quite old so could be out-of-date. Moreover, we're generally sceptical of very large differences between costs and benefits, so we doubt the true ratio is as high as this. Nevertheless, the programme looks to have been a terrible use of resources.

154 |Archived link, retrieved 31 March 2016.`] This estimate seems a little too pessimistic to us, but even so, it looks like it was a huge mistake. 155 | 156 | No-one is sure why this is, but it might be because the young people realised that life in jail wasn’t as bad as they thought, or they came to admire the criminals. 157 | 158 | Some attempts to do good, like Scared Straight, make things worse. Many more fail to have an impact. David Anderson of the Coalition for Evidence Based Policy estimates: 159 | 160 | > Of [social programmes] that have been rigorously evaluated, most (perhaps 75% or more), including those backed by expert opinion and less-rigorous studies, turn out to produce small or no effects, and, in some cases negative effects. 161 | 162 | This suggests that if you chose a charity to get involved in without looking at the evidence, you’ll most likely *have no impact at all*. 163 | 164 | Worse, it’s very hard to tell which programmes are going to be effective ahead of time. Don’t believe us? Try our 10 question quiz, and see if you can guess what’s effective: 165 | 166 | Play the game 167 | 168 | The quiz asks you to guess which social interventions work and which don’t. We’ve tested it on hundreds of people, and they hardly do better than chance. 169 | 170 | So, before you choose a social problem, ask yourself: 171 | 172 | 1. Is there a way to make progress on this problem with rigorous evidence behind it? For instance, lots of studies have shown that malaria nets prevent malaria. 173 | 1. Is this an attempt to try out a new but promising programme, to test whether it works? 174 | 1. Is this a programme with a small but realistic chance of making a massive impact? For instance, research into a key question, or a political campaign. 175 | 176 | If the answer to all of these is no, then it’s probably best to find something else. 177 | 178 | (Read more about whether it’s fair to say most social programmes don’t work.) 179 | 180 | [`Scared Straight showed juvenile delinquents life inside jail, aiming to scare them away from crime. The only catch: it made them more likely to commit crimes rather than less.`] 181 | 182 | ## Look for the best balance of the factors 183 | 184 | You probably won’t find something that does brilliantly on all three dimensions. Rather, look for what does best on balance. A problem could be worth tackling if it’s extremely big and neglected, even if it seems hard to solve. 185 | 186 | *To get the full details on the framework set out here, see this in-depth article, which also tells you how to make your own comparisons of areas.* 187 | 188 | ## Your personal fit and expertise 189 | 190 | There’s no point working on a problem if you can’t find any roles that are a good fit for you – you won’t be satisfied or have much impact. 191 | 192 | So, once you’ve identified problems that have a good combination of being big, neglected and solvable: 193 | 194 | 1. Consider all the roles you could take to contribute to them. We cover this in a later article. 195 | 1. Narrow those down based on where you expect to be most successful. We’ll discuss how to assess personal fit in a later article. 196 | 197 | If you’re already an expert in a problem, then it’s probably best to work within your area of expertise. It wouldn’t make sense for, say, an economist who’s crushing it to switch into something totally different. However, you could still use the framework to narrow down sub-fields e.g. development economics vs. employment policy. 198 | 199 | ## So what's the world's most urgent problem? 200 | 201 | What are the biggest problems in the world that no-one is talking about and are possible to solve? That’s what we’ll cover next. 202 | 203 | ``` 204 |

If you’re new, go to the start of the guide.

208 |No time now? Join our newsletter and we’ll send you one article each week.

209 |In our career review on medical careers, which is based on the research we mention, we provide an optimistic all considered estimate of 4 DALYs averted per year (mean). Over a 35 year career, that’s 140 DALYs averted. Individual doctors will do more or less depending on their ability and speciality.

53 |A standard conversion rate is 30 DALYs = 1 life saved.

54 |

55 | Source: World Bank, p. 402, retrieved 31-March-2016`].

56 |

57 | Если применить стандартный коэффициент пересчета (среди прочих, используется Всемирным банком), согласно которому 30 дополнительных лет здоровой жизни приравниваются к «спасению одной жизни», то продление жизни на 140 лет можно приравнять к спасению пяти жизней. Без сомнения, это значительный результат, однако гораздо меньший, чем мы привыкли ожидать от врачей. Вот три основные причины такой низкой эффективности:

58 |

59 | 1. Среди ученых бытует мнение, что медицина увеличила среднюю продолжительность жизни только на несколько лет. За последние 100 лет на рост продолжительности жизни больше всего повлияло улучшение питания, санитарных условий, материального благосостояния и других факторов.

60 | 1. Врачи — только часть здравоохранительной системы, которая также зависит от медсестер, больничного персонала, оборудования, инфраструктуры. Эффект от медицинского вмешательства складывается из всех этих элементов.

61 | 1. Что еще важнее, в развитых странах уже много врачей, так что самые важные процедуры будут проведены независимо от того, станете вы врачом или нет. Поэтому *дополнительные* врачи лишь позволяют проводить процедуры, приносящие менее значимые и более сомнительные результаты.

62 |

63 | График ниже демонстрирует этот последний момент: зависимость между количеством врачей и уровнем здоровья в разных странах. По вертикали показан уровень заболеваемости популяции, указанный в Годах жизни, скорректированных по нетрудоспособности («DALY») на 100 000 человек, где один DALY — это год жизни, утраченный из-за болезни. По горизонтали — количество врачей на 100 000 человек.

64 |

65 | [`DALYs per 100,000 people versus doctors per 100,000 people. We used WHO data from 2004. Line is the best fitting hyperbola determined by non-linear least square regression. Full explanation in this paper.`]

66 |

67 | Можно увидеть, что значения DALY остаются практически неизменными, когда на 100 000 человек приходится более 150 врачей. После этого момента (которого достигли почти все развитые страны) дополнительные врачи, в среднем, мало что меняют.

68 |

69 | Поэтому, если вы станете врачом в богатой стране вроде США или Великобритании, вам, вероятно, удастся сделать больше, чем на многих других работах, и если вы будете выдающимся врачом, вы принесёте даже большую пользу, но едва ли ваше влияние на мир будет поистине значительным.

70 |

71 | На самом деле уже в следующей статье, мы продемонстрируем, как практически любой выпускник колледжа может сделать для спасения жизней больше, чем обычный доктор. Кроме того, в этом руководстве мы поговорим о многих других примерах распространенных, но неэффективных способов делать добро.

72 |

73 | Эти открытия подтолкнули Грега к тому, что вместо клинической медицины он начал заниматься здравоохранением. Доводы, которые на это повлияли, мы разберем в этом руководстве.

74 |

75 | ## Люди, которые больше остальных повлияли на мир - кто они?

76 |

77 | Данные о том, сколько людей спасают доктора, не назовешь вдохновляющими. Но некоторые врачи изменили мир гораздо сильнее. Давайте разберем несколько примеров профессиональных путей, которые больше всего повлияли на человечество за время его существования, и посмотрим, какие из этого мы сможем сделать выводы. Начнем с медицинских исследований.

78 |

79 | Доктор Давид Налин открыл способ лечения людей, страдающих от диареи, в 1968 году, когда он работал в лагере для беженцев на границе между Бангладеш и Мьянмой. Он обнаружил, что если поить пациентов водой, в которой в нужных пропорциях растворены сахар и соль, регидратация будет происходить с той же скоростью, что и потеря воды организмом. Этот спосбо предотвратить смерть от обезвоживания был гораздо более дешевым, чем обычное лечение внтуривенными капельницами.

80 |

81 | [`Доктор Налин помог спасти миллионы жизней, и способ сделать это был простым: давать пациентам с диареей воду с солью и сахаром.`]

82 |

83 | С тех пор этот очень простой способ лечения стал известен по всему миру, и количество детей, которое умирает в год от диареи, упало с 5 миллионов до 1,3 миллионов. По оценкам исследователей, этот способ лечения спас приблизительно 50 миллонов жизней, в основном детских:

84 |

87 |85 | Since the adoption of this inexpensive and easily applied intervention, the worldwide mortality rate for children with acute infectious diarrhoea has plummeted from 5 million to about 1.3 million deaths per year. Over fifty million lives have been saved in the past 40 years by the implementation of ORT. 86 |

88 | Источник: Science Heroes. Сссылка на архив, полученный 4 марта 2016 г.

89 | 90 | Грубо говоря, это помогло спасти в год 50/40 = 1,25 миллионов жизней. Если бы доктор Налин сделал свое открытие на 5 месяцев раньше, (5/12)*1,25 = 0,52 миллионов - вот сколько еще людей он бы спас. Эти оценка очень приблизительна, на самом деле количество может отличаться на порядки в любую сторону. Пояснения ищите в сносках. 91 | 92 | Если бы доктор Налин занимался чем-то другим, кто-то другой наверняка изборел бы этот способ лечения. Но если мы предположим, что доктор Налин сделал это всего на 5 месяцев раньше, чем его гипотетический конкурент, уже только это помогло бы спасти около 500 000 людей, которые бы в другом случае погибли. По этим приблизительным расчетам влияние доктора Налина можно считать в 100 000 раз большим, чем у обычного доктора: 93 | 94 | [`Жизни, которые спас доктор Налин`] 95 | 96 | Но даже если мы остаемся в рамках медицинских исследований, открытие доктора Налина еще не самый выдающийся пример работы, которая повлияла на всех. Открытие групп крови Карлом Ландштейнером помогло спасти десятки миллионов жизней по оценке Sciense Heroes. Если верить их данным, наибольшее влияние переливание крови начало оказывать с 1955 года. Если считать, что 2,7 процедур переливания крови приблизительно соответствовали 1 спасенной жизни, то только в США эта процедура спасает 4,5 миллионов человек в год. Это значит, что в год переливание крови спасало от смерти 1,5% населения страны. Чтобы получить общее количество, эту долю населения Северной Америки, Европы, Австралии, Новой Зеландии и некоторых стран Азии и Африки просуммировали. Оценка преувеличивает полезность переливаний крови в первые десятилетия, но вовсе не учитывает развивающиеся страны: 97 |101 |98 | Superman of Science Makes Landmark Discovery - Over 1 Billion Lives Saved So Far

99 |Every source quoted an amazing number of transfusions and potential lives saved in countries and regions worldwide. High impact years began around 1955 and calculations are loosely based on 1 life saved per 2.7 units of blood transfused. In the USA alone an estimated 4.5 million lives are saved each year. From these data I determined that 1.5% of the population was saved annually by blood transfusions and I applied this percentage on population data from 1950-2008 for North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of Asia and Africa. This rate may inflate the effectiveness of transfusions in the early decades but excludes the developing world entirely. 100 |

102 | Источник: Science Heroes. Сссылка на архив, полученный 4 марта 2016 г.

103 | 104 | Если считать, что каждый год этот метод спасал одинаковое количество людей, получится, что это приблизительно 10 миллионов человек в год. Если бы доктор Ландштейнер сделал открытие на два года раньше, он бы спас еще 20 миллионов человек. 105 | 106 | Оценка очень приблизительная, в реальности числа могут различаться на порядки как в одну, так и в другую сторону. Вероятнее, что они завышены, чем занижены. Мы скептически относимся к подсчетам Science Heroes. К тому же, у нас есть простая модель увеличения степени влияния. Основная часть жизней была спасена в современную эпоху, только когда у большинства человечества появился доступ к медицине, поэтому не исключено, что ускорение открытия не оказало бы никакого серьезного влияния. С другой стороны, открытие групп крови наверняка стало основой для других научных прорывов - а их влияние мы в подсчетах игнорируем. Тем не менее, наш главный тезис верен: влияние Ландштейнера было гораздо большим, чем у обычного врача. 107 | This is a highly approximate estimate and could easily be off by an order of magnitude in either direction, and seem more likely to be too high than too low. We’re a bit sceptical of the Science Heroes figures. Moreover, our attempt at modelling the speed-up is very simple. Since most of the lives were saved in the modern era once a large number of people had medical care, it’s possible that speeding up the discovery wouldn’t have had much impact at all. On the other hand, the discovery of blood groups probably made other scientific advances possible, and we’re ignoring their impact. Nevertheless, the basic point stands: Landsteiner's impact was likely vastly greater than a typical doctor. 108 | 109 | [`Жизни, котрые спас доктор Ландштейнер`] 110 | 111 | Дальше в руководстве мы переключимся с медицины на другие виды деятельности и расскажем вам о математике Алане Тьюринге и бюрократе Викторе Жданове. 112 | 113 | Хотя давайте мыслить еще шире. Роджер Бэкон и Галилей придумали научный метод исследования, без которого вообще не состоялось бы ни одно из открытий, о которых мы говорили, и были бы невозможны такие технологические достижения, как Великая индустриальная революция. Эти люди сделали куда больше добра, чем самые выдающиеся практикующие врачи. 114 | 115 | ### Неизвестный советский подполковник, который спас вам жизнь 116 | 117 | [``] 118 | 119 | Или рассмотрим историю Станислава Петрова, подполковника совестской армии во время холодной вонйы. Дело было в 1983 году. Петров был на дежурстве на ракетной базе СССР, когда системы раннего оповещения предположительно засекли надвигающийся ракетно-ядерный удар со стороны США. По протоколу нужно было нанести ответный удар. 120 | 121 | Но Петров не нажал на кнопку, рассудив, что ракет было слишком мало, чтобы оправдать контратаку. 122 | 123 | Если бы он приказал атаковать, с немалой вероятностью погибли бы сотни миллионов людей. Это могло бы даже привести к началу ядерной войны, которая привела бы к миллиардам смертей, — а в худшем случае, к концу цивилизации. Если подходить к оценке консервативно, наверное, на счёт Петрова можно записать спасение миллиарда жизней. Но это, вполне вероятно, будет преуменьшением, так как ядерная война ращрушила бы научный, культурный, экономический и все другие фомры прогресса, что привело бы к гибели огромного числа людей в долгосрочной перспективе. Так что подвиг Петрова, вероятно, превосходит заслуги вышеупомянутых людей. 124 | 125 | [``] 126 | 127 | ## What does this spread in impact mean for your career? 128 | 129 | We’ve seen that some careers have had huge positive effects, and some have vastly more than others. 130 | 131 | Some component of this is due to luck – the people mentioned above were in the right place at the right time, affording them the opportunity to have an impact that they might not have otherwise received. You can’t guarantee you’ll make an important medical discovery. 132 | 133 | But it wasn’t all luck: Landsteiner and Nalin chose to use their medical knowledge to solve some of the most harmful health problems of their day, and it was foreseeable that someone high up in the Soviet military could have a large impact by preventing conflict during the Cold War. So, what does this mean for you? 134 | 135 | People often wonder how they can “make a difference”, but if some careers can result in thousands of times more impact than others, this isn’t the right question. Two career options can both “make a difference”, but one could be dramatically better than the other. 136 | 137 | Instead, the key question is, “how can I make the most difference?” In other words: what can you do to give yourself a chance of having one of the highest-impact careers? Because the highest-impact careers achieve so much, a small increase in your chances means a great deal. 138 | 139 | The examples above also show that the highest-impact paths might not be the most obvious ones. Being an officer in the Soviet military doesn’t sound like the best career for a would-be altruist, but Petrov probably did more good than our most celebrated leaders, not to mention our most talented doctors. Having a big impact might require doing something a little unconventional. 140 | 141 | So how much impact can *you* have if you try, while still doing something personally rewarding? It’s not easy to have a big impact, but there’s a lot you can do to increase your chances. That’s what we’ll cover in the next couple of articles. 142 | 143 | But first, let’s clarify what we mean by “making a difference”. We’ve been talking about lives saved so far, but that’s not the only way to do good in the world. 144 | 145 | ## What does it mean to “make a difference?” 146 | 147 | Everyone talks about “making a difference” or “changing the world” or “doing good” or “impact”, but few ever define what they mean. 148 | 149 | So here’s our definition. Your social impact is given by: 150 | 151 | > The number of people whose lives you improve, and how much you improve them. 152 | 153 | This means you can increase your social impact in two ways: by helping more people, or by helping the same number of people to a greater extent (pictured below). 154 | 155 |  156 | 157 | We also include the lives you improve in the future, so you can also increase your impact by helping in ways that have long-term benefits. For example, if you improve the quality of government decision-making, you might not see many quantifiable short-term results, but you will have solved lots of other problems over the long-run. 158 | 159 | ``` 160 |Many people disagree about what it means to make the world a better place. But most agree that it’s good if people have happier, more fulfilled lives, in which they reach their potential. So, our definition is narrow enough that it captures this idea. 163 |

Moreover, as we’ll show, some careers do far more to improve lives than others, so it captures a really important difference between options. If some paths can do good equivalent to saving hundreds of lives, while others have little impact at all, that’s an important difference. 164 |

But, the definition is also broad enough to cover many different ways to make the world a better place. It’s even broad enough to cover environmental protection, since if we let the environment degrade, the future of civilisation might be threatened. In that way, protecting the environment improves lives. 165 |

Many of our readers also expand the scope of their concern to include non-human animals, which is one reason why we did a profile on factory farming. 166 |

That said, the definition doesn’t include *everything* that might matter. You might think the environment deserves protection even if it doesn’t make people better off. Similarly, you might value things like justice and aesthetic beauty for their own sake. 167 |

In practice, our readers value many different things. Our approach is to focus on how to improve lives, and then let people independently take account of what else they value. To make this easier, we try to highlight the main value judgments behind our work. It turns out there’s a lot we can say about how to do good in general, despite all these differences. 168 |

We are always uncertain about how much impact different actions will have, but that’s okay, because we can use probabilities to make the comparison. For instance, a 90% chance of helping 100 people is roughly equivalent to a 100% chance of helping 90 people. Though we’re uncertain, we can quantify our uncertainty and make progress. 170 |

Moreover, we can still use rules of thumb to compare different courses of action. For instance, in an upcoming article we argue that, all else equal, it’s higher-impact to work on neglected areas. So, even if we can’t precisely *measure* social impact, we can still be *strategic* by picking neglected areas. We’ll cover many more rules of thumb for increasing your impact in the upcoming articles. 171 |

(Read more about the definition of social impact.) 172 |

Continue → 183 |

If you’re new, go to the start of the guide. 184 |

No time right now? Join our newsletter and we’ll send you one article each week. 185 |

Note that ACE has been criticised by Harrison Nathan, but we agree with many of the responses made by ACE here.`] 37 | 38 | If Ilan had just handed out business cards at networking conferences, this would have probably never happened. And this illustrates what many people miss about networking: the value of joining a great community. 39 | 40 | If you become a trusted member of a community, you can gain hundreds of potential allies at once, because once one person vouches for you, they can introduce you to everyone else. That means it’s like networking but one hundred times faster. 41 | 42 | In fact, getting involved in the right community is perhaps the single biggest thing you can do to make friends, advance your career, and have a greater impact. You’ll not only improve your connections, but also your knowledge, character, motivation, and more. 43 | 44 | In this article, we’ll explain how our community can help and how to get involved. 45 | 46 | If you’d like to get involved right away, the easiest thing to do is to join the effective altruism newsletter: 47 | 48 | ``` 49 |

57 | 60 | ``` 61 | 62 | ## Why joining a community is so beneficial 63 | 64 | [`Nothing spells community like the letters c, o, m, m, u, n, i, t, & y. Thanks, Large Group of People Holding Word Community/ Getty Images.`] 65 | 66 | There are lots of great communities out there. We’ve enjoyed being part of Y Combinator’s entrepreneur community – it made us more ambitious and more effective at running a startup…hopefully. We’ve also enjoyed participating in the Skoll social entrepreneurship community, the Oxford philosophy “scene”, the World Economic Forum’s Young Global Shapers, and many others. 67 | 68 | Joining any good community can be a great boost to your career. In part, this is because you’ll get all the benefits of connections that we covered earlier: finding jobs, gaining up-to-date information and becoming more motivated. But it goes beyond that. 69 | 70 | Let’s suppose I want to build and sell a piece of software. One approach would be to learn all the skills needed myself – design, engineering, marketing and so on. 71 | 72 | A much better approach is to form a team who are skilled in each area, and then build it together. Although I’ll have to share the gains with the other people, the size of the gains will be much larger, so we’ll all win. 73 | 74 | [``] 75 | 76 | One thing that’s going on here is specialisation: each person can focus on a specific skill, and get really good at it, which lets them be more effective. 77 | 78 | Another factor is that the team can also share fixed costs – they can share the same company registration, operational procedures and so on. It’s also not three times harder to raise three times as much money from investors. This lets them achieve economies of scale. 79 | 80 | In sum, we get what’s called the “gains from trade”. Three people working together can achieve more than three times as much as an individual. 81 | 82 | It’s the same when doing good. Rather than have everyone try to do everything, it’s more effective for people to specialise and work together. 83 | 84 | An especially good thing about trade is that you can do it with people who *don’t* share your goals. Suppose you run an animal rights charity and meet someone who runs a global health charity. You don’t think global health is a pressing problem, and the other person doesn’t think animal rights is a pressing problem, so neither of you think the other’s charity has much impact. But suppose you know a donor who might give to their charity, and they know a donor who might give to your charity. You can trade: if you both make introductions, which is a small cost, you might both find a new donor, which is a big benefit. 85 | 86 | [``] 87 | 88 | So, you both end up with a big benefit for a small cost, so you both win. This shows valuable to join a community even if the people in it have different aims from your own. 89 | 90 | That said, it’s far better again to join a community of people who *do* share your goals. That’s why there’s a community we especially want to highlight, which many people have not yet heard about: the effective altruism community. 91 | 92 | ## How can the effective altruism community boost your career? 93 | 94 | > “Effective altruism – efforts that actually help people rather than making you feel good or helping you show off – is one of the great new ideas of the twenty-first century.”Note that ACE has been criticised by Harrison Nathan, but we agree with many of the responses made by ACE here.`] 37 | 38 | If Ilan had just handed out business cards at networking conferences, this would have probably never happened. And this illustrates what many people miss about networking: the value of joining a great community. 39 | 40 | If you become a trusted member of a community, you can gain hundreds of potential allies at once, because once one person vouches for you, they can introduce you to everyone else. That means it’s like networking but one hundred times faster. 41 | 42 | In fact, getting involved in the right community is perhaps the single biggest thing you can do to make friends, advance your career, and have a greater impact. You’ll not only improve your connections, but also your knowledge, character, motivation, and more. 43 | 44 | In this article, we’ll explain how our community can help and how to get involved. 45 | 46 | If you’d like to get involved right away, the easiest thing to do is to join the effective altruism newsletter: 47 | 48 | ``` 49 |

57 | 60 | ``` 61 | 62 | ## Why joining a community is so beneficial 63 | 64 | [`Nothing spells community like the letters c, o, m, m, u, n, i, t, & y. Thanks, Large Group of People Holding Word Community/ Getty Images.`] 65 | 66 | There are lots of great communities out there. We’ve enjoyed being part of Y Combinator’s entrepreneur community – it made us more ambitious and more effective at running a startup…hopefully. We’ve also enjoyed participating in the Skoll social entrepreneurship community, the Oxford philosophy “scene”, the World Economic Forum’s Young Global Shapers, and many others. 67 | 68 | Joining any good community can be a great boost to your career. In part, this is because you’ll get all the benefits of connections that we covered earlier: finding jobs, gaining up-to-date information and becoming more motivated. But it goes beyond that. 69 | 70 | Let’s suppose I want to build and sell a piece of software. One approach would be to learn all the skills needed myself – design, engineering, marketing and so on. 71 | 72 | A much better approach is to form a team who are skilled in each area, and then build it together. Although I’ll have to share the gains with the other people, the size of the gains will be much larger, so we’ll all win. 73 | 74 | [``] 75 | 76 | One thing that’s going on here is specialisation: each person can focus on a specific skill, and get really good at it, which lets them be more effective. 77 | 78 | Another factor is that the team can also share fixed costs – they can share the same company registration, operational procedures and so on. It’s also not three times harder to raise three times as much money from investors. This lets them achieve economies of scale. 79 | 80 | In sum, we get what’s called the “gains from trade”. Three people working together can achieve more than three times as much as an individual. 81 | 82 | It’s the same when doing good. Rather than have everyone try to do everything, it’s more effective for people to specialise and work together. 83 | 84 | An especially good thing about trade is that you can do it with people who *don’t* share your goals. Suppose you run an animal rights charity and meet someone who runs a global health charity. You don’t think global health is a pressing problem, and the other person doesn’t think animal rights is a pressing problem, so neither of you think the other’s charity has much impact. But suppose you know a donor who might give to their charity, and they know a donor who might give to your charity. You can trade: if you both make introductions, which is a small cost, you might both find a new donor, which is a big benefit. 85 | 86 | [``] 87 | 88 | So, you both end up with a big benefit for a small cost, so you both win. This shows valuable to join a community even if the people in it have different aims from your own. 89 | 90 | That said, it’s far better again to join a community of people who *do* share your goals. That’s why there’s a community we especially want to highlight, which many people have not yet heard about: the effective altruism community. 91 | 92 | ## How can the effective altruism community boost your career? 93 | 94 | > “Effective altruism – efforts that actually help people rather than making you feel good or helping you show off – is one of the great new ideas of the twenty-first century.”