├── 10

├── cc_license.png

├── stats.py

├── _publish.yml

└── 10.qmd

├── 11

├── cc_license.png

├── text.txt

├── _publish.yml

└── 11.qmd

├── 12

├── cc_license.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 12.qmd

├── .gitignore

├── 01

├── cc_license.png

├── install-python-macos.png

├── install-python-windows.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 01.qmd

├── 02

├── cc_license.png

├── idle-editor.png

├── idle-shell.png

├── python-components.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 02.qmd

├── 03

├── cc_license.png

├── python_names_1.png

├── python_names_2.png

├── python_names_3.png

├── python_object.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 03.qmd

├── 04

├── cc_license.png

├── debug-control.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 04.qmd

├── 05

├── cc_license.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 05.qmd

├── 06

├── cc_license.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 06.qmd

├── 07

├── cc_license.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 07.qmd

├── 08

├── cc_license.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 08.qmd

├── 09

├── cc_license.png

├── _publish.yml

└── 09.qmd

└── README.md

/.gitignore:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | *.html

2 | *_files/

3 | .quarto/

4 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/01/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/01/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/02/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/02/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/02/idle-editor.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/02/idle-editor.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/02/idle-shell.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/02/idle-shell.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/03/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/03/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/04/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/04/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/05/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/05/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/06/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/06/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/07/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/07/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/08/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/08/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/09/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/09/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/10/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/10/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/11/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/11/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/11/text.txt:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Hello!

2 |

3 | This is just a test file containing some random text.

4 |

5 | Nice!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/12/cc_license.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/12/cc_license.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/03/python_names_1.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/03/python_names_1.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/03/python_names_2.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/03/python_names_2.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/03/python_names_3.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/03/python_names_3.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/03/python_object.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/03/python_object.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/04/debug-control.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/04/debug-control.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/02/python-components.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/02/python-components.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/01/install-python-macos.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/01/install-python-macos.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/01/install-python-windows.png:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cbrnr/python-intro-short/HEAD/01/install-python-windows.png

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/10/stats.py:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | def mean(values):

2 | s = 0

3 | for v in values:

4 | s += v

5 | return s / len(values)

6 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/01/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 01.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: a72c34e2-4269-4334-98e3-da5bbe1f3543

4 | url: https://python-intro-01.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/02/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 02.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: c58043f1-5fb4-4a14-98e1-9377f35c27f2

4 | url: https://python-intro-02.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/03/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 03.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: dc83fc48-f792-4bb4-94df-6b5a343f2c03

4 | url: https://python-intro-03.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/04/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 04.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: 8f32aeb8-20cd-4c78-9c85-9df0741dfb1a

4 | url: https://python-intro-04.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/05/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 05.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: 4590ff6e-e4d1-488c-a002-ed91d426b62d

4 | url: https://python-intro-05.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/06/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 06.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: bcf4fe67-8285-4973-9b70-de9793a850a6

4 | url: https://python-intro-06.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/07/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 07.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: f2821280-5ff9-4714-b8dd-5dc83c83a2a2

4 | url: https://python-intro-07.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/08/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 08.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: 512e6f5e-2385-47ff-be9a-3aecda1597b0

4 | url: https://python-intro-08.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/09/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 09.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: c5bf0e88-a616-4a90-a7dc-c82b11e5141c

4 | url: https://python-intro-09.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/10/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 10.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: 6a604355-05b1-4e2d-a351-e0edcae4f134

4 | url: https://python-intro-10.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/11/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 11.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: 53dcfd69-96bf-4dd0-ad2e-8e69b9341b84

4 | url: https://python-intro-11.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/12/_publish.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | - source: 12.qmd

2 | netlify:

3 | - id: 7a7d7ec3-938e-4db9-9ed4-6780bade865a

4 | url: https://python-intro-12.netlify.app

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/README.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # A short introduction to Python

2 |

3 | 1. [Basics](https://python-intro-01.netlify.app/)

4 | 2. [Python environment](https://python-intro-02.netlify.app/)

5 | 3. [Names, expressions, statements](https://python-intro-03.netlify.app/)

6 | 4. [Functions](https://python-intro-04.netlify.app/)

7 | 5. [Conditions](https://python-intro-05.netlify.app)

8 | 6. [Loops](https://python-intro-06.netlify.app)

9 | 7. [Strings](https://python-intro-07.netlify.app)

10 | 8. [Lists](https://python-intro-08.netlify.app)

11 | 9. [Dictionaries](https://python-intro-09.netlify.app)

12 | 10. [Modules and packages](https://python-intro-10.netlify.app)

13 | 11. [Input and output](https://python-intro-11.netlify.app)

14 | 12. [Exercises](https://python-intro-12.netlify.app)

15 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/12/12.qmd:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | title: "12 – Exercises"

3 | subtitle: "Introduction to Python"

4 | author: "Clemens Brunner"

5 | date: 2025-02-05

6 | format:

7 | html:

8 | page-layout: full

9 | engine: jupyter

10 | highlight-style: github

11 | title-block-banner: true

12 | theme:

13 | light: flatly

14 | dark: darkly

15 | cap-location: margin

16 | ---

17 |

18 | ## Introduction

19 |

20 | This section contains additional exercises to practice the concepts learned in the previous sections. This is still work in progress, so more exercises will be added over time.

21 |

22 |

23 | ## Exercise 1

24 |

25 | Write a function `collatz` that takes a positive integer `n` as an argument and returns a list of the [Collatz sequence](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collatz_conjecture) starting with `n`. The Collatz sequence is defined as follows: if `n` is even, the next number is half of `n`. If `n` is odd, the next number is three times `n` plus 1. The sequence ends when it reaches 1.

26 |

27 |

28 | ---

29 |  This document is licensed under the [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) by [Clemens Brunner](https://cbrnr.github.io/).

30 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/09/09.qmd:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | title: "9 – Dictionaries"

3 | subtitle: "Introduction to Python"

4 | author: "Clemens Brunner"

5 | date: 2025-02-05

6 | format:

7 | html:

8 | page-layout: full

9 | engine: jupyter

10 | highlight-style: github

11 | title-block-banner: true

12 | theme:

13 | light: flatly

14 | dark: darkly

15 | cap-location: margin

16 | ---

17 |

18 | ## Introduction

19 |

20 | The last built-in data type we are going to cover is the dictionary (`dict`). Just like its name implies, a dictionary is a mapping data type, which maps keys to values. It works a little like a real-word dictionary. Let's assume we wanted to look up the German translation of "cat". We'd flip through the pages of an English-German dictionary until we found the entry for "cat". This entry would contain the German translation "Katze". In this example, "cat" is the key and "Katze" is its value. Therefore, a dictionary is a mapping from keys to values. A dictionary can contain many key/value pairs.

21 |

22 |

23 | ## Creating dictionaries

24 |

25 | We use curly braces to create a `dict`, and we supply a comma-separated list of key/value pairs inside the braces (the key/value pairs are separated by colons). Here's an example:

26 |

27 | ```{python}

28 | d = {"house": "Haus", "cat": "Katze", "snake": "Schlange"}

29 | ```

30 |

31 | Alternatively, we can also use the `dict` function and create key/value pairs with keyword arguments:

32 |

33 | ```{python}

34 | d = dict(house="Haus", cat="Katze", snake="Schlange")

35 | ```

36 |

37 | Note that in the second version, dictionary keys need to be valid Python names, whereas the first version is more flexible. For example, we can use an `int` as a key, but only when we use curly bracket notation:

38 |

39 | ```{python}

40 | {1: "one", 2: "two"}

41 | ```

42 |

43 | The `dict` function raises a syntax error, because argument names must not start with a digit:

44 |

45 | ```{python}

46 | #| error: true

47 | dict(1="one", 2="two")

48 | ```

49 |

50 | Just like in lists and strings, Python uses square brackets to access individual elements in a dict. However, because dictionaries are not ordered, we use its keys to retrieve their corresponding values. Let's demonstrate this with the dictionary we defined previously:

51 |

52 | ```{python}

53 | d["cat"]

54 | ```

55 |

56 | ```{python}

57 | d["house"]

58 | ```

59 |

60 | When we use a key that does not exist in the dictionary, Python raises an error:

61 |

62 | ```{python}

63 | #| error: true

64 | d["dog"]

65 | ```

66 |

67 | Dictionaries are mutable, which means that we can modify existing dictionary entries:

68 |

69 | ```{python}

70 | d["snake"] = "Python"

71 | d

72 | ```

73 |

74 | We can add new entries simply by assigning a value to a new key using square bracket notation:

75 |

76 | ```{python}

77 | d["bug"] = "Wanze"

78 | d

79 | ```

80 |

81 | :::{.callout-important}

82 | Again, order is irrelevant in dictionaries. There is no first, second or last item in a dictionary – values can only be accessed by their key.

83 | :::

84 |

85 | So far, we have used strings as dictionary keys. However, we can actually use any *immutable* data type as a key, including integers, floats, and tuples. Importantly, we cannot use lists as keys, because lists are mutable. This restriction does *not* apply to dictionary *values*, which can be mutable or immutable objects.

86 |

87 | ```{python}

88 | x = {13: "A", "c": 2.22, (0, 1): [1, 2, 3]}

89 | x

90 | ```

91 |

92 | ```{python}

93 | #| error: true

94 | x[[4, 5, 6]] = "X" # try to add new entry with mutable key (list)

95 | ```

96 |

97 | The previous assignment demonstrates what happens when we try to create a dictionary entry with a list as a key: we get a `TypeError` (note that the error message says that the type is *unhashable* – for most purposes, unhashable means mutable, although technically these are different concepts).

98 |

99 |

100 | ## Working with dictionaries

101 |

102 | Not surprisingly, we can use the `len` function to determine the number of entries in a dictionary:

103 |

104 | ```{python}

105 | d = {"house": "Haus", "cat": "Katze", "snake": "Schlange"}

106 | len(d)

107 | ```

108 |

109 | Notice that an entry is a key/value pair. We can get the keys or values separately with the `keys` and `values` methods, respectively:

110 |

111 | ```{python}

112 | d.keys()

113 | ```

114 |

115 | ```{python}

116 | d.values()

117 | ```

118 |

119 | These methods return list-like objects (you can basically think of them as lists).

120 |

121 | Using the `in` keyword, we can check if the dictionary contains a specific *key*:

122 |

123 | ```{python}

124 | "cat" in d

125 | ```

126 |

127 | ```{python}

128 | "Katze" in d

129 | ```

130 |

131 | If we want to check for a specific *value*, we can perform our query on `d.values()` instead:

132 |

133 | ```{python}

134 | "cat" in d.values()

135 | ```

136 |

137 | ```{python}

138 | "Katze" in d.values()

139 | ```

140 |

141 |

142 | ## Iterating over dictionaries

143 |

144 | Dictionaries are iterable, and if we create a loop over a dict, we actually loop over its *keys*:

145 |

146 | ```{python}

147 | for key in d:

148 | print(key)

149 | ```

150 |

151 | Using the current key in each iteration, we can access the corresponding value via indexing:

152 |

153 | ```{python}

154 | for key in d:

155 | print(key, ":", d[key])

156 | ```

157 |

158 | Of course, we could also iterate over `d.values()` specifically, but often it is necessary to iterate over both keys and values simultaneously. The dict method `items` returns key/value pairs as tuples:

159 |

160 | ```{python}

161 | d.items()

162 | ```

163 |

164 | We can use this list-like sequence of tuples in a loop, which means that we get a tuple in each iteration. However, instead of assigning one name to the tuple, we can unpack its two items into two distinct names (this is called *tuple unpacking*):

165 |

166 | ```{python}

167 | for key, value in d.items():

168 | print(key, "=>", value)

169 | ```

170 |

171 | :::{.callout-tip}

172 | Here's another example of tuple unpacking:

173 |

174 | ```{python}

175 | a, b = 12, 13

176 | a

177 | ```

178 |

179 | ```{python}

180 | b

181 | ```

182 |

183 | The tuple `12, 13` on the right-hand side contains two items. On the left-hand side, we assign a name to each item in the tuple, effectively unpacking the tuple into individual names. Because Python always evaluates the right-hand side first, the canonical way to swap two values in Python is very short and sweet:

184 |

185 | ```{python}

186 | a, b = b, a

187 | ```

188 |

189 | This swaps the values of `a` and `b`, which we can confirm by printing their values:

190 |

191 | ```{python}

192 | a

193 | ```

194 |

195 | ```{python}

196 | b

197 | ```

198 | :::

199 |

200 |

201 | ## Setting default values

202 |

203 | We have already seen that accessing a non-existing dictionary entry results in a `KeyError`:

204 |

205 | ```{python}

206 | #| error: true

207 | d = {"house": "Haus", "cat": "Katze", "snake": "Schlange"}

208 | d["dog"]

209 | ```

210 |

211 | There are two additional options to get values from a dictionary without raising an error. First, the `get` method returns a user-defined default value (by default `None`) if a key does not exist:

212 |

213 | ```{python}

214 | d.get("dog") # returns None

215 | ```

216 |

217 | ```{python}

218 | d.get("dog", "UNDEFINED") # returns "UNDEFINED" if the key does not exist

219 | ```

220 |

221 | ```{python}

222 | d.get("cat", "UNDEFINED") # returns the value if the key exists

223 | ```

224 |

225 | However, `get` does not automatically *add* new entries to the dictionary (in our example, there is still no `"dog"` entry in `d`):

226 |

227 | ```{python}

228 | d

229 | ```

230 |

231 | If we do want to add new key/value pairs whenever we access a non-existing key, we can use the `setdefault` method instead of `get`:

232 |

233 | ```{python}

234 | d.setdefault("dog", "UNDEFINED")

235 | ```

236 |

237 | ```{python}

238 | d

239 | ```

240 |

241 |

242 | ## Exercises

243 |

244 | 1. Create a dictionary containing three arbitrary elements. How can you access those three values individually?

245 |

246 | 2. Add a fourth entry to the dictionary.

247 |

248 | 3. Iterate over the dictionary and output all key/value pairs on separate lines.

249 |

250 | 4. Access a non-existing element in the dictionary with the three different options discussed in this chapter.

251 |

252 | ---

253 |  This document is licensed under the [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) by [Clemens Brunner](https://cbrnr.github.io/).

254 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/01/01.qmd:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | title: "1 – Basics"

3 | subtitle: "Introduction to Python"

4 | author: "Clemens Brunner"

5 | date: 2025-02-05

6 | format:

7 | html:

8 | page-layout: full

9 | engine: jupyter

10 | highlight-style: github

11 | title-block-banner: true

12 | theme:

13 | light: flatly

14 | dark: darkly

15 | cap-location: margin

16 | ---

17 |

18 | ## Introduction

19 |

20 | In this workshop, you will learn the basics of the Python programming language. This is a course for beginners, so you do not need to be fluent in any other programming language. In fact, it is perfectly fine if you have never programmed before.

21 |

22 | We will start from scratch and learn how to set up a working Python environment, including package management and related housekeeping tasks. Once Python is installed on your computer, we will dive into the elegant syntax and basic building blocks of the Python language, such as functions, conditions, and loops. We will then discuss important data types in Python, focussing on strings, lists, and dictionaries. Afterwards, we will start using these building blocks to solve simple tasks such as reading/writing text from/to a file. Finally, we will briefly introduce widely used third-party packages for scientific computing. Specifically, we will touch upon packages that allow us to efficiently work with numerical data and tabular data.

23 |

24 | With that out of the way, let's get started!

25 |

26 |

27 | ## Overview

28 |

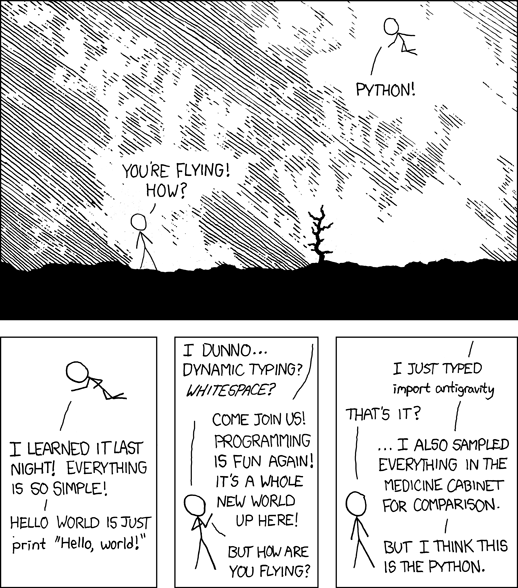

29 | [](https://xkcd.com/353/)

30 |

31 | Here are some facts about Python:

32 |

33 | - Simple, elegant, and fun to learn and use

34 | - Open source (not only [free as in beer but also free as in speech](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gratis_versus_libre))

35 | - Cross-platform (Python runs on Windows, macOS, and Linux)

36 | - General-purpose programming language, meaning that Python is not specifically designed to be extremely good in one particular area such as statistics – it can be used for many different applications including data science, web servers, graphical user interfaces, programming the [Raspberry Pi](https://www.raspberrypi.org/), ...

37 | - Batteries included approach (the [standard library](https://docs.python.org/3/library/) shipping with Python contains many useful things ready for use)

38 | - Huge number of [third-party packages](https://pypi.org/) that implement even more useful things

39 | - Large and friendly community

40 |

41 | Python was first released by [Guido van Rossum](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guido_van_Rossum) way back in 1991, and its popularity has skyrocketed in the past years. While there are many ways to measure the popularity of a programming language, Python has consistently ranked among the top languages for years (for example according to [PYPL](https://pypl.github.io/PYPL.html), the [TIOBE index](https://www.tiobe.com/tiobe-index/), and the [IEEE Spectrum Top Programming Languages](https://spectrum.ieee.org/top-programming-languages-2024)). Also, one of the results of the [Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2024](https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2024/) is that Python is among the [most popular technologies](https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2024/technology/#most-popular-technologies) as well as highly [admired and desired](https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2024/technology/#admired-and-desired).

42 |

43 | So far, we have only talked about Python without seeing what the language actually looks like. Here's a sneak peak at what you will be able to understand after completing this course (gray boxes contain Python code, whereas the result of a line of code is shown directly below it):

44 |

45 | ```{python}

46 | print("Hello World!")

47 | ```

48 |

49 | ```{python}

50 | "only lower case letters".upper()

51 | ```

52 |

53 | ```{python}

54 | for i in range(10):

55 | print(i, end=", ")

56 | ```

57 |

58 | ```{python}

59 | [k**2 for k in range(0, 100, 10)]

60 | ```

61 |

62 | In summary, Python is extremely popular and fun to use, so in the next section we're going to discuss how to install it on our computer.

63 |

64 |

65 | ## Installation

66 |

67 | The [official Python website](https://www.python.org/) is a great resource for everything related to Python. The [download](https://www.python.org/downloads/) section contains installers for many platforms, including Windows and macOS. If you are on Linux, I recommend that you use your package manager (such as `apt`, `yum`, or `pacman`) to install Python (in most cases, Python will already be installed anyway).

68 |

69 | On Windows, make sure to check the option *"Add python.exe to PATH"*. I strongly recommend to use the default values for all other settings.

70 |

71 |

72 |

73 | On macOS, run both "Install Certificates" and "Update Shell Profile" commands available in the application folder after the installation is complete:

74 |

75 |

76 |

77 |

78 | ## First steps

79 |

80 | After installing Python, it is instructive to enter some simple Python commands and see what happens. The program which understands and interprets Python commands is called the *Python interpreter*. It can be invoked in various ways, but one of the easiest options is to run it from the command line (or terminal), a powerful text-based interface provided by your operating system.

81 |

82 | - On Windows, you should see a start menu entry inside the Python folder named "Python 3.12 (64-bit)" (or similar). Alternatively, you can launch Python from a regular command prompt by starting the "Terminal" app and typing `python` followed by Enter.

83 | - On macOS, start the "Terminal" app and type `python3` (followed by Enter).

84 | - On Linux, start your favorite terminal app and type `python` (followed by Enter).

85 |

86 | :::{.callout-important}

87 | The Python interpreter executable is called `python` on Windows and Linux, but `python3` on macOS. If you use macOS, remember to always use `python3` to start the Python interpreter.

88 | :::

89 |

90 | A simple (black or white) text window will open – this is the so-called *interactive* Python interpreter. You can enter commands, and Python will happily try to execute what you just typed (the interactive interpreter is also called the [REPL](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Read%E2%80%93eval%E2%80%93print_loop), short for read-eval-print loop).

91 |

92 | The interactive Python interpreter includes a *prompt*, which is typically the character sequence `>>>`. This prompt indicates that Python is ready to receive user input. You can type a Python command and hit Enter to evaluate it. Python will immediately show the result of this command (if any) on the next line.

93 |

94 | :::{.callout-note}

95 | Throughout the course material, we show Python code in gray boxes and never include the prompt `>>>`.

96 | :::

97 |

98 | Let's try to use Python as a calculator. Python supports the four basic arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division):

99 |

100 | ```{python}

101 | 1 + 1

102 | ```

103 |

104 | ```{python}

105 | 10 - 7

106 | ```

107 |

108 | ```{python}

109 | 7 * 8

110 | ```

111 |

112 | ```{python}

113 | 120 / 7

114 | ```

115 |

116 | In addition, Python can also compute the result of integer division and its remainder:

117 |

118 | ```{python}

119 | 120 // 7

120 | ```

121 |

122 | ```{python}

123 | 120 % 7

124 | ```

125 |

126 | Exponentiation (raising one number to the power of another) uses the `**` operator:

127 |

128 | ```{python}

129 | 2**64

130 | ```

131 |

132 | Finally, Python knows the correct order of operations and is able to deal with parentheses ([PEMDAS](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_operations#Mnemonics)):

133 |

134 | ```{python}

135 | (13 + 6) * 8 - 12 / (2.5 + 1.6)

136 | ```

137 |

138 | Note that Python accepts only regular parentheses (and not square or curly brackets) to group expressions:

139 |

140 | ```{python}

141 | ((13 + 6) * 8) / (12 / (2.5 + 1.6))

142 | ```

143 |

144 | :::{.callout-important}

145 | Python uses a *dot* as the decimal separator and not a comma (as is common in German-speaking regions).

146 | :::

147 |

148 | For more advanced calculations such as square roots, logarithms, or trigonometric functions, we need to import (activate) the [`math`](https://docs.python.org/3/library/math.html) module to use the various functions it provides:

149 |

150 | ```{python}

151 | import math

152 | ```

153 |

154 | After that, we can compute the square root of 2 as follows:

155 |

156 | ```{python}

157 | math.sqrt(2)

158 | ```

159 |

160 | Mathematical constants such as Euler's number *e* (`math.e`) and $\pi$ (`math.pi`) are also available:

161 |

162 | ```{python}

163 | 1 + math.sqrt(math.e) * 7 - 2 * math.pi * 1.222

164 | ```

165 |

166 |

167 | ## Exercises

168 |

169 | 1. Install Python and start the interactive interpreter. Which Python version do you use and how can you find out?

170 |

171 | 2. What happens if you type `import antigravity` and `import this` in the Python interpreter?

172 |

173 | 3. Compute the result of the division $4 / 0.4$. In addition, compute the integer result and the remainder.

174 |

175 | 4. Assume you measured the following values: 11, 27, 15, 10, 33, 18, 25, 22, 39, and 11. Calculate the arithmetic mean in a single line of code.

176 |

177 | 5. Evaluate the following mathematical expression in a single line of code (don't forget to `import math` for the square root and $\pi$):

178 |

179 | $$\frac{(5^5 - \pi) \cdot \frac{19}{3}}{\sqrt{13} + 7^{\frac{2}{3}}}$$

180 |

181 | ---

182 |  This document is licensed under the [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) by [Clemens Brunner](https://cbrnr.github.io/).

183 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/06/06.qmd:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | title: "6 – Loops"

3 | subtitle: "Introduction to Python"

4 | author: "Clemens Brunner"

5 | date: 2025-02-05

6 | format:

7 | html:

8 | page-layout: full

9 | engine: jupyter

10 | highlight-style: github

11 | title-block-banner: true

12 | theme:

13 | light: flatly

14 | dark: darkly

15 | cap-location: margin

16 | ---

17 |

18 | ## Introduction

19 |

20 | It is often necessary to repeat statements a certain (or undefined) number of times. For example, let's assume that we wanted to print "Hello!" five times. Rather naively, we could write this simply as:

21 |

22 | ```{python}

23 | print("Hello")

24 | print("Hello")

25 | print("Hello")

26 | print("Hello")

27 | print("Hello")

28 | ```

29 |

30 | Although this does the job, it is really cumbersome to repeat the same line of code multiple times. Furthermore, imagine we made a mistake and we really wanted to print "Bye" instead of "Hello" – we'd have to change our code in five different locations!

31 |

32 |

33 | ## `for`-loops

34 |

35 | Python supports two types of loops (`for`-loops and `while`-loops), which enable us to perform repeated actions. Like functions and conditions, loops control the program flow. Our previous example could be rewritten as follows:

36 |

37 | ```{python}

38 | for i in range(5):

39 | print("Hello")

40 | ```

41 |

42 | This is obviously much shorter than writing out each repetition manually (even more so if the loop involves more iterations). Furthermore, if we want to make changes, we only need to do it once inside the body of the loop.

43 |

44 | Let's analyze the structure of a `for`-loop in Python. The first part should look familiar: just like functions and conditions, `for`-loops start with a header. This time, the header is introduced with the `for` keyword. Next, the loop header defines a name (`i` in our case), which will get individual values of a sequence-like object, which is specified last (`range(5)` in the example). In each iteration of the loop, `i` gets the current value of the sequence we are iterating over. A colon concludes the loop header.

45 |

46 | The indented part after the header forms the body of the loop. This code block is what is actually repeated (in our example, `print("Hello")` is repeatedly called five times).

47 |

48 | :::{.callout-note}

49 | Since we are not using the value of `i` in the loop body, it is common to use the name `_` instead. Note that this is just a convention, there is nothing special about the name `_` at all.

50 | :::

51 |

52 | We can further inspect what's going on by printing `i` inside the loop:

53 |

54 | ```{python}

55 | for i in range(5):

56 | print(i)

57 | ```

58 |

59 | :::{.callout-tip}

60 | Note that `i` remains available after the loop – its value will be `4`, because this was the most recent assignment in the last iteration of the loop.

61 | :::

62 |

63 | Alright, so `range(5)` produces a sequence of five numbers, starting at 0 and ending with 4. The loop iterates over all elements of this sequence until it is exhausted, after which the loop stops. In each iteration of the loop, `i` contains the i-th element of the sequence, and this particular value is used when running the body of the loop.

64 |

65 | :::{.callout-note}

66 | Actually, `range` can also be called with two arguments, which are then interpreted as start and stop values of the created range. However, the stop value does not belong to the sequence anymore (this is because the difference between stop and start is supposed to equal the number of elements):

67 |

68 | ```{python}

69 | list(range(2, 8)) # 8 - 2 = 6 values (from 2 to 7)

70 | ```

71 |

72 | Note that we have to use `list` in order to see all the elements that `range` creates at once (more on lists soon).

73 |

74 | If called with a third argument, `range` interprets this argument as a step size:

75 |

76 | ```{python}

77 | list(range(2, 8, 2)) # values from 2 to 7, but only every second value

78 | ```

79 | :::

80 |

81 | A loop can iterate not only over `range`, but over *any sequence-like* object (a data type that can contain more than one item). We will learn more about three widely-used container types (strings, lists, and dictionaries) in the next chapters.

82 |

83 | Here's a short preview of what a loop can do. First, we can iterate over a string:

84 |

85 | ```{python}

86 | for s in "Hello World!":

87 | print(s)

88 | ```

89 |

90 | Here, `s` gets all characters of the string `"Hello World!"` sequentially as the loop iterates. That is, in the first iteration, `s` contains the character `"H"`, in the second `"e"`, and so on. The `print` function is called in each iteration with the current character `s` as its argument (it automatically inserts a newline at the end, though this can be changed with the `end` parameter).

91 |

92 | A list is another popular sequence-like data type that can contain elements of arbitrary types (more on this later). We can iterate over a list like this:

93 |

94 | ```{python}

95 | a = ["Hello", "world!", "I", "love", "Python!"]

96 |

97 | for element in a:

98 | print(element)

99 | ```

100 |

101 |

102 | ### Breaking and continuing loops

103 |

104 | Python lets us preemptively break out of a loop or jump to the next iteration from anywhere in the loop body using the `break` and `continue` keywords, respectively.

105 |

106 | Sometimes, we want to stop a loop early, like in the following example that demonstrates how to search for a character within a given string:

107 |

108 | ```{python}

109 | i = 0 # current position (index)

110 |

111 | for c in "Hide and seek":

112 | if c == "e": # we're searching for the first "e"

113 | break

114 | i += 1 # increment i by 1

115 |

116 | print(i)

117 | ```

118 |

119 | This example searches for the first occurrence of the character `"e"` within the string `"Hide and seek"`. If it finds it, the name `i` contains the position (index) of this character within the string (`3` in this example, because we initialize `i` with zero). Notice that once we have found the character (`c == "e"`), we immediately break out of the loop (which means Python immediately jumps to the end of the loop, which is the `print(i)` function call). As we will see soon, `break` is especially useful in `while`-loops.

120 |

121 | :::{.callout-note}

122 | The statement `i += 1` is shorthand for `i = i + 1` (increment `i` by one).

123 | :::

124 |

125 | The next example demonstrates the use of the `continue` statement, which causes Python to immediately jump back to the loop header and begin the next iteration.

126 |

127 | ```{python}

128 | for num in range(2, 10):

129 | if num % 2 == 0:

130 | print("Found an even number", num)

131 | continue

132 | print("Found an odd number", num)

133 | ```

134 |

135 | Of course, we could have used an `else` branch here, but the goal was to show an example for the `continue` statement.

136 |

137 |

138 | ## `while`-loops

139 |

140 | In addition to `for`-loops, Python also supports `while`-loops. In general, both loop types can be used interchangeably, but `while`-loops are especially useful when we need a loop that never stops (an infinite loop), or in cases where we don't know in advance how many iterations we are going to perform.

141 |

142 | Here's our first `for`-loop example transformed to a `while`-loop:

143 |

144 | ```python

145 | i = 0

146 |

147 | while i < 5:

148 | print(i)

149 | i += 1

150 | ```

151 |

152 | In this case, we would prefer the `for`-loop, because it requires us to write only two lines of code as opposed to four lines for the `while`-loop.

153 |

154 | However, `while`-loops are useful if we don't know the number of iterations in advance, which is often the case when user input is involved. Consider the following example, which prompts the user to input a character and runs until the input equals `"q"`:

155 |

156 | ```python

157 | while True:

158 | line = input("> (enter 'q' to quit) ")

159 | if line == "q":

160 | break

161 | ```

162 |

163 | The `while`-loop makes this use case quite natural. Apparently, `while True` is *always* `True`, so the loop will go on forever. However, notice that there is a `break` statement inside the loop body, which will exit the loop immediately. This will only happen if the user input (stored in `line`) equals `"q"`.

164 |

165 | Here's another fun little example which involves a (potentially) infinite `while`-loop. It also contains a condition with `if`, `elif`, and `else` blocks. The task of the user is to guess the value of `number` (which is 23 in this case, but we assume that the user doesn't know this value). If the guess is correct, we `break` out of the loop and the program is done. If the user's guess is incorrect, we give a hint and go to the next iteration.

166 |

167 | ```python

168 | number = 23

169 |

170 | while True:

171 | guess = int(input("Enter an integer: ")) # int converts the input to a number

172 | if guess == number:

173 | print("Congratulations, you guessed it.")

174 | break

175 | elif guess < number:

176 | print("No, it is a little higher than that.")

177 | else:

178 | print("No, it is a little lower than that.")

179 | ```

180 |

181 |

182 | ## Exercises

183 |

184 | 1. Modify the number guessing game by reporting the number of guesses it took a user to guess the correct number!

185 |

186 | 2. Iterate over the list `lst = ["I", "love", "Python"]` and in each iteration, `print` the current list element on the screen.

187 |

188 | 3. Iterate over the list `lst = ["I", "love", "Python"]` and in each iteration, use a second loop to iterate over the current string and `print` each character on the screen followed by a `-`. Use the `end="-"` argument in `print` to get the desired output, which should look like this: `I-l-o-v-e-P-y-t-h-o-n-`.

189 |

190 | 4. Iterate over the list `[1, 13, 25, -11, 17, 24, 9, -1, 2, 3]` until you encounter the first even number. Once you find this number, break out of the loop and print the number on the screen. Since we have not learned about lists yet, use a for-loop to solve this problem (we could also use a while-loop, but we need to know more about lists before we can do so).

191 |

192 | ---

193 |  This document is licensed under the [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) by [Clemens Brunner](https://cbrnr.github.io/).

194 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/05/05.qmd:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | title: "5 – Conditions"

3 | subtitle: "Introduction to Python"

4 | author: "Clemens Brunner"

5 | date: 2025-02-05

6 | format:

7 | html:

8 | page-layout: full

9 | engine: jupyter

10 | highlight-style: github

11 | title-block-banner: true

12 | theme:

13 | light: flatly

14 | dark: darkly

15 | cap-location: margin

16 | ---

17 |

18 | ## Introduction

19 |

20 | As our programs become more complex, we will often need to run a block of code only if a specific condition is met. For example, we might want to output a message only if a certain number is less than some specified value. This is where conditions come in handy – they allow us to run code only if a condition is fulfilled. Conditions are another important building block of almost any real-world program. Just like functions, conditions allow us to control the flow of execution.

21 |

22 |

23 | ## Comparisons

24 |

25 | A condition is based on a comparison. A comparison is an expression, which means that it has a value. Because a condition can only be either true or false, Python has a special data type `bool` exactly for this purpose. Therefore, a `bool` can either be `True` or `False` (notice the capitalization of the first letters):

26 |

27 | ```{python}

28 | x = True

29 | type(x)

30 | ```

31 |

32 | ```{python}

33 | y = False

34 | type(y)

35 | ```

36 |

37 |

38 | ### Comparison operators

39 |

40 | Python has the following binary comparison operators:

41 |

42 | - Equality `==`

43 | - Inequality `!=`

44 | - Less than `<`

45 | - Greater than `>`

46 | - Less than or equal to `<=`

47 | - Greater than or equal to `>=`

48 |

49 | Here are some examples:

50 |

51 | ```{python}

52 | x = 2

53 | x == 2

54 | ```

55 |

56 | :::{.callout-tip}

57 | Mixing up the equality operator `==` with the assignment operator `=` is a common mistake, so make sure to use the correct operator in your code!

58 | :::

59 |

60 | ```{python}

61 | x != 2

62 | ```

63 |

64 | ```{python}

65 | x > 2

66 | ```

67 |

68 | ```{python}

69 | x < 10

70 | ```

71 |

72 | We can combine two or more comparisons using the `and` and `or` keywords:

73 |

74 | ```{python}

75 | x > 0 and x < 10

76 | ```

77 |

78 | ```{python}

79 | x == -2 or x == 2

80 | ```

81 |

82 | ```{python}

83 | x > 5 or x < 10 and x > 8

84 | ```

85 |

86 | :::{.callout-tip}

87 | Python has a shortcut for checking if a number is within a certain range. Instead of writing:

88 |

89 | ```{python}

90 | x > 0 and x < 10

91 | ```

92 |

93 | We can write:

94 |

95 | ```{python}

96 | 0 < x < 10

97 | ```

98 | :::

99 |

100 | The `not` keyword inverts a boolean expression:

101 |

102 | ```{python}

103 | not True

104 | ```

105 |

106 | ```{python}

107 | not False

108 | ```

109 |

110 | ```{python}

111 | not 0 < x < 10

112 | ```

113 |

114 | We can always use parentheses to change precedence or improve readability:

115 |

116 | ```{python}

117 | not (0 < x < 10)

118 | ```

119 |

120 | ```{python}

121 | (x < 0) or (x >= 2)

122 | ```

123 |

124 | :::{.callout-note}

125 | Python also has an exclusive or (XOR) operator `^`, which returns `True` if exactly one of the two operands is `True`:

126 |

127 | ```{python}

128 | True ^ False

129 | ```

130 |

131 | ```{python}

132 | True ^ True

133 | ```

134 | :::

135 |

136 |

137 | ### Comparing floating point numbers

138 |

139 | Python distinguishes between integer numbers (`int`) and floating point numbers (`float`). These two types represent numbers differently. Most noteably, `int` numbers have *exact* internal representations, whereas `float` numbers can only be stored with *limited precision*. This can lead to subtle issues, especially when comparing two floating point numbers for equality:

140 |

141 | ```{python}

142 | 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 == 0.3

143 | ```

144 |

145 | A common solution is to allow a certain amount of "wiggle space" in the comparison:

146 |

147 | ```{python}

148 | (0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1) - 0.3 < 1e-15

149 | ```

150 |

151 | The `math` module has a function called `isclose`, which can be used exactly for this purpose:

152 |

153 | ```{python}

154 | import math

155 | math.isclose(0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1, 0.3)

156 | ```

157 |

158 | :::{.callout-tip}

159 | Python supports expressing decimal numbers using [scientific notation](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_notation) with powers of ten. It uses the symbol `e`, which can be read as "times ten to the power of". The following examples illustrate this concept:

160 |

161 | ```{python}

162 | 1e0 # 1 times 10 to the power of 0

163 | ```

164 |

165 | ```{python}

166 | -4e0 # -4 times 10 to the power of 0

167 | ```

168 |

169 | ```{python}

170 | 1e1 # 1 times 10 to the power of 1

171 | ```

172 |

173 | ```{python}

174 | 3.5e2 # 3.5 times 10 to the power of 2

175 | ```

176 |

177 | ```{python}

178 | 1e-2 # 1 times 10 to the power of -2

179 | ```

180 |

181 | ```{python}

182 | 1e-15 # 1 times 10 to the power of -15 = 0.000000000000001

183 | ```

184 |

185 | Note that the result is always a regular `float` number.

186 | :::

187 |

188 |

189 | ## Conditions

190 |

191 | We are now ready to discuss conditions. A condition checks whether a specific comparison (boolean expression) is `True` or `False`. Python runs an associated block of code only if the result is `True`.

192 |

193 | Here's the structure of a condition in pseudo-code:

194 |

195 | ```

196 | if :

197 |

198 | ...

199 | ...

200 | elif : # optional

201 |

202 | ...

203 | elif : # optional

204 |

205 | ...

206 | ...

207 | else: # optional

208 |

209 | ```

210 |

211 | The indented lines of code belonging to a specific condition are only executed if the corresponding condition is `True`. We can test several conditions sequentially by using `elif` statements after the initial `if` statement. If no condition is `True`, Python runs the code in the `else` block.

212 |

213 | Importantly, Python only executes the *first* block of code where the condition returns `True`. If this happens, all other `elif` and `else` blocks are skipped.

214 |

215 |

216 | ### Example 1

217 |

218 | Let's work through some examples. Here's a simple condition consisting of only one `if` statement:

219 |

220 | ```{python}

221 | a = 2

222 |

223 | if a > 0:

224 | print("a is a positive number")

225 | print("this is good to know")

226 | ```

227 |

228 | If we run these lines, Python will execute the indented lines of code, because `a` is in fact greater than zero. Since the condition `a > 0` is `True`, we get the two lines of output.

229 |

230 | If we take the same `if` block, but set `a = 0` before, we do not get any output, because Python does not run the two lines (the condition `a > 0` is `False`):

231 |

232 | ```{python}

233 | a = 0

234 |

235 | if a > 0:

236 | print("a is a positive number")

237 | print("this is good to know")

238 | ```

239 |

240 |

241 | ### Example 2

242 |

243 | We can add an optional `else` branch, which Python runs if none of the previous conditions evaluated to `True`:

244 |

245 | ```{python}

246 | a = 0

247 |

248 | if a > 0:

249 | print("a is a positive number")

250 | print("this is good to know")

251 | else:

252 | print("a is either 0 or a negative number")

253 | ```

254 |

255 | Now because `a > 0` is `False`, Python will run the code associated with the `else` branch.

256 |

257 |

258 | ### Example 3

259 |

260 | Also optionally, we can add (an arbitrary number of) `elif` branches, for example:

261 |

262 | ```{python}

263 | a = -5

264 |

265 | if a > 0:

266 | print("a is a positive number")

267 | print("this is good to know")

268 | elif a < 0:

269 | print("a is a negative number")

270 | else:

271 | print("a is 0")

272 | ```

273 |

274 |

275 | ### Example 4

276 |

277 | Due to the fact that Python only runs the code associated with the *first* condition yielding `True`, the *order* of conditions is important. Consider the following two examples containing identical conditions, but in a different order:

278 |

279 | ```{python}

280 | a = 4

281 |

282 | if a > 5:

283 | print("One")

284 | elif a < 10:

285 | print("Two")

286 | elif a == 4:

287 | print("Three")

288 | else:

289 | print("Four")

290 | ```

291 |

292 | Now we swap the order of the two `elif` branches:

293 |

294 | ```python

295 | a = 4

296 |

297 | if a > 5:

298 | print("One")

299 | elif a == 4:

300 | print("Three")

301 | elif a < 10:

302 | print("Two")

303 | else:

304 | print("Four")

305 | ```

306 |

307 | This example demonstrates that the order of branches is important.

308 |

309 |

310 | ### Example 5

311 |

312 | We haven't really talked about data types other than numeric ones yet, but Python can also compare non-numeric types such as strings:

313 |

314 | ```{python}

315 | p = "Python"

316 | r = "R"

317 | p == r

318 | ```

319 |

320 | ```{python}

321 | p > r

322 | ```

323 |

324 | ```{python}

325 | p < r

326 | ```

327 |

328 | Therefore, we can use such comparisons in a condition:

329 |

330 | ```{python}

331 | if p != r:

332 | print("Python and R are different, but both are pretty cool!")

333 | ```

334 |

335 |

336 | ## Exercises

337 |

338 | 1. Write the following program:

339 | - First, ask the user to type in two numbers `x` and `y`. You can use the `input` function to get user input. Note that `input` always returns a `str`, but you can use the `int` function to convert a number contained in a `str` to `int`!

340 | - Once you have both numbers `x` and `y`, check if their sum is greater than 50.

341 | - If the sum is greater than 50, print "Greater than 50!".

342 | - If the sum is less than 50, print "Less than 50!".

343 | - If the sum is exactly 50, print "50!".

344 |

345 | 2. Write a function `is_odd`, which has one parameter `x` and returns `True` if `x` is odd. If `x` is even, the function returns `False`. Note that you can check if a number is odd if dividing this number by 2 has a remainder of 1 (for even numbers, the remainder is 0). Use the `%` operator to compute the remainder!

346 |

347 | 3. Convert the following nested conditions into one block with `if`/`elif`/`else` branches:

348 | ```python

349 | if x > 0:

350 | print("x is positive")

351 | else:

352 | if x < 0:

353 | print("x is negative")

354 | else:

355 | print("x is equal to 0")

356 | ```

357 |

358 | ---

359 |  This document is licensed under the [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) by [Clemens Brunner](https://cbrnr.github.io/).

360 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/03/03.qmd:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | title: "3 – Names, Expressions, and Statements"

3 | subtitle: "Introduction to Python"

4 | author: "Clemens Brunner"

5 | date: 2025-02-05

6 | format:

7 | html:

8 | page-layout: full

9 | engine: jupyter

10 | highlight-style: github

11 | title-block-banner: true

12 | theme:

13 | light: flatly

14 | dark: darkly

15 | cap-location: margin

16 | ---

17 |

18 | ## Objects, values, and types

19 |

20 | Everything in Python is an *object*. An object is an entity which has a value, a type, and a unique identifier. For example, the number `1` we used in our arithmetic calculations is actually an object. It has the value `1` and the type `int` (which means integer number). Here are a few additional examples of objects:

21 |

22 | ```{python}

23 | 1

24 | ```

25 |

26 | ```{python}

27 | 2.15

28 | ```

29 |

30 | ```{python}

31 | "Hello world!"

32 | ```

33 |

34 | ```{python}

35 | '3'

36 | ```

37 |

38 | As we already know, Python outputs the *value* of the last command automatically in the REPL (the interactive interpreter). That's why we know the value of the `1` object is `1`, and the value of the `"Hello world!"` object is `'Hello world!'` (never mind the different quotes for now, we'll discuss these so-called strings in a later chapter).

39 |

40 | To find out the type of a given object, we can use the built-in `type` function as follows:

41 |

42 | ```{python}

43 | type(1)

44 | ```

45 |

46 | ```{python}

47 | type(2.15)

48 | ```

49 |

50 | ```{python}

51 | type("Hello world!")

52 | ```

53 |

54 | ```{python}

55 | type('3')

56 | ```

57 |

58 | Apparently, integer numbers are of type `int` (integer number), decimal numbers are `float` (floating point number), and character strings enclosed by single or double quotes are `str` (string) objects.

59 |

60 | Conceptually, we can think of an object as an entity of a specific type with a specific value living in the computer's memory:

61 |

62 |

63 |

64 | Each object also has a unique identifier. We can use the `id` function to find out:

65 |

66 | ```{python}

67 | id(3)

68 | ```

69 |

70 | ```{python}

71 | id(4)

72 | ```

73 |

74 | The actual identifier numbers are irrelevant (and probably different on your computer). The only thing that's interesting about these identifiers is whether or not they are identical. In the previous example, the object `3` has a different identifier than the object `4`, so we know that these are two different objects.

75 |

76 |

77 | ## Names

78 |

79 | Objects can have names (in other programming languages, names are often called variables). We can assign a name to an object with the assignment operator `=` as follows:

80 |

81 | ```{python}

82 | a = 1

83 | ```

84 |

85 | This attaches the name `a` to the object `1` (of type `int`). We can visualize names as tags or labels attached to an object.

86 |

87 |

88 |

89 | Python lets us reassign an existing name to a different object. Notice how the object on the left does not have a name anymore after we re-assign `a`:

90 |

91 | ```{python}

92 | a = 2.4

93 | ```

94 |

95 |

96 |

97 | An object can also have more than one name attached to it:

98 |

99 | ```{python}

100 | b = a

101 | ```

102 |

103 |

104 |

105 | We can confirm that `a` and `b` point to the same object by inspecting their corresponding identifiers:

106 |

107 | ```{python}

108 | id(a)

109 | ```

110 |

111 | ```{python}

112 | id(b)

113 | ```

114 |

115 | Indeed, they are identical, so there is just one object with two names. If we want to check if two names are attached to one and the same object, we can also use the `is` keyword as a shortcut:

116 |

117 | ```{python}

118 | a is b

119 | ```

120 |

121 | The type of a name corresponds to the type of the object the name is attached to:

122 |

123 | ```{python}

124 | type(a)

125 | ```

126 |

127 | ```{python}

128 | type(b)

129 | ```

130 |

131 | Whenever Python works with a name, it always replaces it with the value of the corresponding object. Furthermore, Python always evaluates the right-hand side of an assignment first before assigning the name. Consider the following example:

132 |

133 | ```{python}

134 | x = 11

135 | 9 + x # x is evaluated to 11, then 9 + 11 is evaluated to 20

136 | ```

137 |

138 | After this line, `x` still has the value `11`:

139 |

140 | ```{python}

141 | x

142 | ```

143 |

144 | We now reassign the name `x` to a different object `2`:

145 |

146 | ```{python}

147 | x = 2

148 | 2 * x # x is evaluated to 2, then 2 * 2 is evaluated to 4

149 | ```

150 |

151 | After this line, `x` has the value `2`. However, we can reassign `x` again and even use the old value of `x` in the right-hand side of the assignment:

152 |

153 | ```{python}

154 | x = 2 * x # first evaluate the right-hand side to 2 * 2 = 4, then assign x = 4

155 | x

156 | ```

157 |

158 |

159 | ## Choosing names

160 |

161 | ### Basic rules

162 |

163 | Valid names can contain letters (lower and upper case), digits, and underscores (but a name cannot start with a digit). [PEP8](https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/#naming-conventions) lists recommendations for choosing good names – we only need to remember one rule for now: almost all names should be lowercase, and if necessary can also contain underscores, such as `lower_case_with_underscores`.

164 |

165 | Names should convey meaning, so instead of a generic `x` or `i`, we should try to find a name that tells us something about its intended use. Also, it is good practice to use English (and not e.g. German) names, because you never know who will read your code in the future.

166 |

167 | Here are a few examples for naming an object which represents the number of students in a school class:

168 |

169 | ```{python}

170 | number_of_students_in_class = 23 # too long

171 | NumberOfStudents = 23 # wrong style, not separated with underscores

172 | n_students = 23 # pretty nice

173 | n = 23 # probably too short (but may be OK sometimes)

174 | ```

175 |

176 |

177 | ### Keywords

178 |

179 | Python defines several reserved keywords that are a core part of the language. They *cannot* be used to name objects, so it is important to know what they are. The following code snippet produces a list of all keywords:

180 |

181 | ```{python}

182 | import keyword

183 | keyword.kwlist

184 | ```

185 |

186 | For example, this means that you cannot use the name `lambda`. If you do, Python will generate an error:

187 |

188 | ```{python}

189 | #| error: true

190 | lambda = 7

191 | ```

192 |

193 |

194 | ### Built-in functions

195 |

196 | Python also has a number of [built-in functions](https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html) that are always available (without importing). Although it is possible to assign the names of these built-in functions to other objects, it is considered bad practice, because it might lead to subtle bugs. The following code generates a list of all built-ins:

197 |

198 | ```python

199 | dir(__builtins__)

200 | ```

201 |

202 | :::{.callout-tip}

203 | If you really want to use a name that is already taken by a built-in function, it is better to change the name slightly by appending an underscore. For example, instead of using `lambda`, you could use `lambda_`.

204 | :::

205 |

206 |

207 | ## Operators

208 |

209 | In general, operators work with objects. We have already used several (arithmetic) operators such as `+`, `-`, `*`, `/`, `**`, `//`, and `%`. Some operators are *binary* and require *two* operands (for example, the multiplication `2 * 3`), whereas other operators are *unary* and require only *one* operand (for example, the negation `-5`).

210 |

211 |

212 | ## Expressions

213 |

214 | An *expression* is any combination of values, names, and operators. Importantly, an expression *always evaluates to a single value* (or short, an expression *has* a value). Here are a few examples for expressions (remember that their values are automatically printed in the REPL):

215 |

216 | ```{python}

217 | 17 # just one value

218 | ```

219 |

220 | ```{python}

221 | 23 + 4**2 - 2 # four values and three operators

222 | ```

223 |

224 | ```{python}

225 | n = 25 # an assignment is not an expression!

226 | ```

227 |

228 | ```{python}

229 | n # one name (evaluates to its value)

230 | ```

231 |

232 | ```{python}

233 | n + 5 # a name, an operator, and a value

234 | ```

235 |

236 | Python reduces an expression to a *single value*. A more complex expression is evaluated step by step according to operator precedence rules (think [PEMDAS](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_operations#Mnemonics)) from left to right. As we've already discussed, Python evaluates the right-hand side of an assignment first before assigning a name.

237 |

238 |

239 | ## Statements

240 |

241 | A statement is a unit of code which Python can run. This is a rather broad definition, and statements therefore include expressions as a special case (in other words, an expression is a statement with a value). However, there are also statements that do *not* have a value, such as an assignment. Here are two examples for statements that are not expressions:

242 |

243 | ```{python}

244 | x = 13

245 | print("Hello world!")

246 | ```

247 |

248 | Note that although the `print` statement generates output, this output is not its value (try assigning a name to the function call)!

249 |

250 |

251 | ## Exercises

252 |

253 | 1. Determine if the following names are valid, and if they are, decide if they comply with PEP8 conventions. Describe whether each name is a good name for an object containing a string or an integer number.

254 | - `2x`

255 | - `_`

256 | - `x23`

257 | - `_name`

258 | - `alpha`

259 | - `lambda`

260 | - `Name`

261 | - `X2`

262 | - `sum`

263 | - `test-case`

264 |

265 | 2. Consider these three assignments:

266 | ```python

267 | width = 17

268 | height = 12

269 | delimiter = "."

270 | ```

271 | Determine both the value and type of the following expressions:

272 | - `width / 2`

273 | - `height / 3`

274 | - `height * 3`

275 | - `height * 3.0`

276 | - `delimiter * 5`

277 | - `2 * (width + height) + 1.5`

278 | - `12 + 3`

279 | - `"12 + 3"`

280 |

281 | 3. Calculate the area and volume of a sphere with radius $r = 5$. Use the names `r`, `area`, and `volume` to compute these quantities. The number $\pi$ is available as `math.pi` after running `import math`.

282 |

283 | 4. What is the type of the value `True`? What is the type of the value `'True'`? What is the type of `math` (which you imported in the previous exercise)?

284 |

285 | ---

286 |  This document is licensed under the [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) by [Clemens Brunner](https://cbrnr.github.io/).

287 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/10/10.qmd:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | title: "10 – Modules and Packages"

3 | subtitle: "Introduction to Python"

4 | author: "Clemens Brunner"

5 | date: 2025-02-05

6 | format:

7 | html:

8 | page-layout: full

9 | engine: jupyter

10 | highlight-style: github

11 | title-block-banner: true

12 | theme:

13 | light: flatly

14 | dark: darkly

15 | cap-location: margin

16 | ---

17 |

18 | ## Introduction

19 |

20 | The core Python programming language can be extended with modules and packages. The [standard library](https://docs.python.org/3/library/index.html), which ships with every Python installation, is a collection of numerous modules for various purposes. In addition, there are thousands of third-party packages available on [PyPI](https://pypi.org/), which can be installed with the `pip` package manager.

21 |

22 | A *module* is a Python script that we can import in order to use whatever is defined in it. A *package* organizes a collection of modules. We will see examples for both modules and packages later in this chapter.

23 |

24 |

25 | ## Importing modules

26 |

27 | We have already used functions from the `math` module (which is part of the standard library). Before using functions defined in a module, we have to import either the entire module or only specific functions from the module. By convention, we import modules at the top of a script.

28 |

29 | Here's an example where we import the entire `math` module and then use some of its names and functions:

30 |

31 | ```{python}

32 | import math

33 | math.pi

34 | ```

35 |

36 | ```{python}

37 | math.e

38 | ```

39 |

40 | ```{python}

41 | math.sin(math.pi)

42 | ```

43 |

44 | ```{python}

45 | math.cos(math.pi)

46 | ```

47 |

48 | After `import math`, we can access the contents of the module by prepending `math.` to the actual names contained in the module (`math.pi`, `math.e`, `math.sin`, and so on).

49 |

50 | The `dir` function lists all definitions contained in a module (we can ignore the dunder names, which are reserved for internal use):

51 |

52 | ```{python}

53 | dir(math)

54 | ```

55 |

56 | If we only want to use a limited number of functions from a module, we can save us some typing by importing specific functions from a module like this:

57 |

58 | ```{python}

59 | from math import pi, sqrt

60 | sqrt(4)

61 | ```

62 |

63 | ```{python}

64 | 2 * 3**2 * pi

65 | ```

66 |

67 | That way, we can use these functions directly as `sqrt` and `pi` instead of `math.sqrt` and `math.pi`, respectively.

68 |

69 |

70 | ## Writing custom modules

71 |

72 | We are not restricted to using predefined modules – Python lets us write our own modules. This is especially useful to structure a longer program into several files. For example, let's assume that we wrote our own `mean` function, which computes the arithmetic mean of a list of numbers with the following relatively naive implementation:

73 |

74 | ```{python}

75 | def mean(values):

76 | s = 0

77 | for v in values:

78 | s += v

79 | return s / len(values)

80 | ```

81 |

82 | We could put this function in our own module called `stats`. This is just a Python file called [`stats.py`](stats.py), and its contents is the function definition.

83 |

84 | Note that this file should be available in the current working directory, which corresponds to the directory that the Python interpreter is currently working in. We can then import either our `stats` module or the `mean` function from our `stats` module directly:

85 |

86 | ```{python}

87 | import stats

88 | dir(stats)

89 | ```

90 |

91 | The only non-dunder name is indeed our `mean` function, which we can now use as:

92 |

93 | ```{python}

94 | stats.mean(range(1, 101))

95 | ```

96 |

97 | Alternatively, we can only import the `mean` function:

98 |

99 | ```{python}

100 | from stats import mean

101 | mean(range(1, 101))

102 | ```

103 |

104 | Optionally, we can rename either the imported module or the imported function during import:

105 |

106 | ```{python}

107 | import stats as st

108 | st.mean([1, 2, 3])

109 | ```

110 |

111 | ```python

112 | from stats import mean as m

113 | m(range(50, 76))

114 | ```

115 |

116 | Sometimes, this is useful when modules or function names are very long. In addition, some popular third-party modules like NumPy are imported with shorter names by convention:

117 |

118 | ```python

119 | import numpy as np # convention

120 | ```

121 |

122 | Behind the scenes, nothing fancy is happening when we use alternative names for imported modules. This is just a shorter version for writing:

123 |

124 | ```python

125 | import numpy # imports module and assigns the name numpy

126 | np = numpy # create another name np (an alias)

127 | del numpy # delete the original name numpy (we still have np)

128 | ```

129 |

130 |

131 | ## Selected examples from the standard library

132 |

133 | We will now briefly discuss some common modules from the standard library. First, note that a `mean` function is already implemented in the `statistics` module:

134 |

135 | ```{python}

136 | import statistics

137 | statistics.mean(range(1, 101))

138 | ```

139 |