├── media

├── simple_ui.webp

├── bsd.svg

├── raw.svg

├── socket.svg

├── frame.svg

├── stack.svg

└── mongoose.svg

├── LICENSE

└── README.md

/media/simple_ui.webp:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cpq/embedded-network-programming-guide/HEAD/media/simple_ui.webp

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/LICENSE:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | MIT License

2 |

3 | Copyright (c) 2023 Sergey Lyubka

4 |

5 | Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy

6 | of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal

7 | in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights

8 | to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell

9 | copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is

10 | furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

11 |

12 | The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all

13 | copies or substantial portions of the Software.

14 |

15 | THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR

16 | IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY,

17 | FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE

18 | AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER

19 | LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM,

20 | OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE

21 | SOFTWARE.

22 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/media/bsd.svg:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/media/raw.svg:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/media/socket.svg:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/media/frame.svg:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/media/stack.svg:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/media/mongoose.svg:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/README.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Embedded network programming guide

2 |

3 | [](https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT)

4 |

5 | This guide is written for embedded developers who work on connected products.

6 | That includes microcontroller based systems that operate in bare metal or

7 | RTOS mode, as well as microprocessor based systems which run embedded Linux.

8 |

9 | ## Prerequisites

10 |

11 | All fundamental concepts are explained in details, so the guide should be

12 | understood by a reader with no prior networking knowledge.

13 |

14 | A reader is expected to be familiar with microcontroller C programming - for

15 | that matter, I recommend reading my [bare metal programming

16 | guide](https://github.com/cpq/bare-metal-programming-guide). I will be using

17 | Ethernet-enabled Nucleo-H743ZI board throughout this guide. Examples for other

18 | architectures are summarized in a table below - this list will expand with

19 | time. Regardless, for the best experience I recommend Nucleo-H743ZI to get the

20 | most from this guide: [buy it on

21 | Mouser](https://www.mouser.ie/ProductDetail/STMicroelectronics/NUCLEO-H743ZI2?qs=lYGu3FyN48cfUB5JhJTnlw%3D%3D).

22 |

23 | ## Network stack explained

24 |

25 | ### Network frame structure

26 |

27 | When any two devices communicate, they exchange discrete pieces of data called

28 | frames. Frames can be sent over the wire (like Ethernet) or over the air (like

29 | WiFi or Cellular). Frames differ in size, and typically range from couple of

30 | dozen bytes to a 1.5Kb. Each frame consists of a sequence of protocol headers

31 | followed by user data:

32 |

33 |

34 |

35 | The purpose of the headers is as follows:

36 |

37 | **MAC (Media Access Control) header** is only 3 fields: destination MAC

38 | address, source MAC addresses, and an upper level protocol. MAC addresses are

39 | 6-byte unique addresses of the network cards, e.g. `42:ef:15:c8:29:a1`.

40 | Protocol is usually 0x800, which means that the next header is IP. MAC header

41 | handles addressing in the local network (LAN).

42 |

43 |

44 | **IP (Internet Protocol) header** has many fields, but the most important are:

45 | destination IP address, source IP address, and upper level protocol. IP

46 | addresses are 4-bytes, e.g. `209.85.202.102`, and they identify a machine

47 | on the Internet, so their purpose is similar to phone numbers. The upper level

48 | protocol is usually 6 (TCP) or 17 (UDP). IP header handles global addressing.

49 |

50 | **TCP or UDP header** has many fields, but the most important are destination

51 | port and source ports. On one device, there can be many network applications,

52 | for example, many open tabs in a browser. Port number identifies

53 | an application.

54 |

55 | **Application protocol** depends on the target application. For example, there

56 | are servers on the Internet that can tell an accurate current time. If you want

57 | to send data to those servers, the application protocol must SNTP (Simple

58 | Network Time Protocol). If you want to talk to a web server, the protocol must

59 | be HTTP. There are other protocols, like DNS, MQTT, etc, each having their own

60 | headers, followed by the application data.

61 |

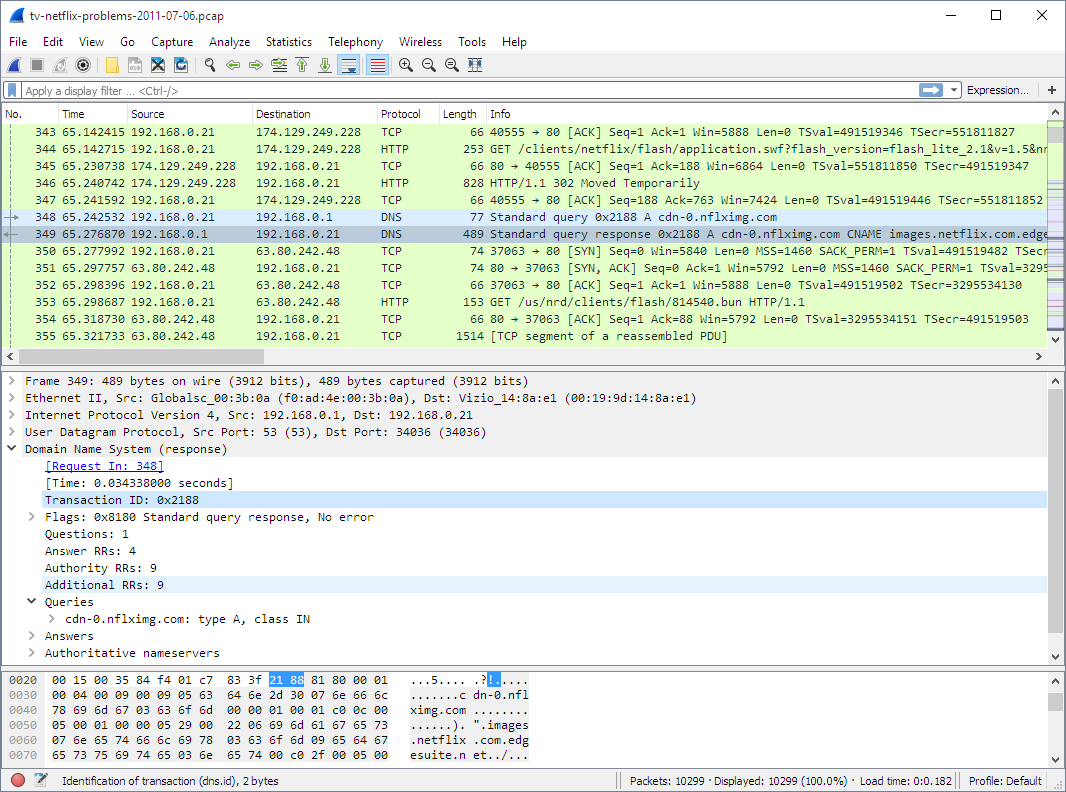

62 | Install [Wireshark](https://www.wireshark.org/) tool to observe network

63 | frames. It helps to identify issues quickly, and looks like this:

64 |

65 |

66 |

67 | The structure of a frame described above, makes it possible to accurately

68 | deliver a frame to the correct device and application over the Internet. When a

69 | frame arrives to a device, a software that handles that frame (a network

70 | stack), is organised in four layers.

71 |

72 | ### Network stack architecture

73 |

74 |

75 |

76 | Layer 1: **Driver layer**, only reads and writes frames from/to network hardware

77 | Layer 2: **TCP/IP stack**, parses protocol headers and handles IP and TCP/UDP

78 | Layer 3: **Network Library**, parses application protocols like DNS, MQTT, HTTP

79 | Layer 4: **Application** - Web dashboard, smart sensor, etc

80 |

81 |

82 | ### DNS request example

83 |

84 | Let's provide an example. In order to show your this guide on the Github, your

85 | browser first needs to find out the IP address of the Github's machine. For

86 | that, it should make a DNS (Domain Name System) request to one of the DNS

87 | servers. Here's how your browser and the network stack work for that case:

88 |

89 |

90 |

91 | **1.** Your browser (an application) asks from the lower layer (library), "what

92 | IP address `github.com` has?". The lower layer (layer 3, a library layer - in

93 | this case, it is a C library) provides an API function `gethostbyname()`

94 | that returns an IP address for a given host name. So everything said below,

95 | essentially describes how `gethostbyname()` works.

96 |

97 | **2.** The library layer gets the name `github.com` and creates a properly

98 | formatted, binary DNS request: `struct dns_request`. Then it calls an API

99 | function `sendto()` provided by the TCP/IP stack layer (layer 2), to send that

100 | request over UDP to the DNS server. The IP of the DNS server is known to the library

101 | from the workstation settings. The UDP port is also known - port 53, a standard

102 | port for DNS.

103 |

104 | **3.** The TCP/IP stack's `sendto()` function receives a chunk of data to send.

105 | it contains DNS request, but `sendto()` does not know that and does not care

106 | about that. All it knows is that this is the piece of user data that needs to

107 | be delievered over UDP to a certain IP address (IP address of a DNS server) on

108 | port 53. Hence TCP/IP stack prepends UDP, IP, and MAC headers

109 | to the user data to form a frame. Then it calls API function `send_frame()`

110 | provided by the driver layer, layer 1.

111 |

112 | **4.** A driver's `send_frame()` function transmits a frame over the wire or

113 | over the air, the frame travels to the destination DNS server. A chain of

114 | Internet routers pass that frame from one to another, until a frame finally hits

115 | DNS server's network card.

116 |

117 | **5.** A network card on the DNS server gets a frame and generates a hardware

118 | interrupt, invoking interrupt handler. It is part of a driver - layer 1. It

119 | calls a function `recv_frame()` that reads a frame from the card, and passes

120 | it up by calling `ethernet_input()` function provided by the TCP/IP stack

121 |

122 | **6.** TCP/IP stack parses the frame, and finds out that it is for the UDP port

123 | 53, which is a DNS port number. TCP/IP stack finds an application that listens

124 | on UDP port 53, which is a DNS server application, and wakes up its `recv()`

125 | call. So, DNS server application that is blocked on a `recv()` call, receives

126 | a chunk of data - which is a DNS request. A library routine parses that request

127 | by extracting a host name, and passes that parsed DNS request to the application.

128 |

129 |

130 | **7.** A DNS server application receives DNS request: "someone wants an

131 | IP address for `github.com`". Then the application layer looks at its

132 | configuration, figures out "Oh, it's me who is responsible for the github.com

133 | domain, and this is the IP address I should respond with". The application

134 | extracts an IP address from the configuration, and calls a library function

135 | "get this IP, wrap into a DNS response, and send back". And the response

136 | travels all the way back in the reverse order.

137 |

138 | ### BSD socket API

139 |

140 | The communication between layers are done via a function calls. So, each

141 | layer has its own API, which upper and lower levels can call. They are not

142 | standardized, so each implementation provides their own set of functions.

143 | However, on OSes like Windows/Mac/Linux/UNIX, a driver and TCP/IP layers are

144 | implemented in kernel, and TCP/IP layer provides a standard API to the

145 | userland which is called a "BSD socket API":

146 |

147 |

148 |

149 | This is done becase kernel code does not implement application level protocols

150 | like MQTT, HTTP, etc, - so it let's user application to implement them in

151 | userland. So, a library layer and an application layer reside in userland.

152 | Some library level routines are provided in C standard library, like

153 | DNS resolution function `gethostbyname()`, but that DNS library functions

154 | are probably the only ones that are provided by OS. For other protocols,

155 | many libraries exist that provide HTTP, MQTT, Websocket, SSH, API. Some

156 | applications don't use any external libraries: they use BSD socket API

157 | directly and implement library layer manually. Usually that is done when

158 | application decides to use some custom protocol.

159 |

160 | Embedded systems very often use TCP/IP stacks that provide the same BSD API as

161 | mainstream OSes do. For example, lwIP (LightWeight IP) TCP/IP stack, Keil's MDK

162 | TCP/IP stack, Zephyr RTOS TCP/IP stack - all provide BSD socket API. Thus let's

163 | review the most important BSD API stack functions:

164 |

165 | - `socket(protocol)` - creates a connection descriptor and assigns an integer ID for it, a "socket"

166 | - `bind(sock, addr)` - assigns a local IP:PORT for a listening socket

167 | - `accept(sock, addr)` - creates a new socket, assigns local IP:PORT

168 | and remote IP:PORT (incoming)

169 | - `connect(sock, addr)` - assigns local IP:PORT and remote IP:PORT for

170 | a socket (outgoing)

171 | - `send(sock, buf, len)` - sends data

172 | - `recv(sock, buf, len)` - receives data

173 | - `close(sock)` - closes a socket

174 |

175 | Some implementations do not implement BSD socket API, and there are perfectly

176 | good reasons for that. Examples for such implementation is lwIP raw API,

177 | and Mongoose Library.

178 |

179 | ### TCP echo server implemented with socket API

180 |

181 | Let me demonstrate the two approaches (using socket and non-socket API) on a simple

182 | TCP echo server example. TCP echo server is a simple application that

183 | listens on a TCP port, receives data from clients that connect to that port,

184 | and writes (echoes) that data back to the client. That means, this application

185 | does not use any application protocol on top of TCP, thus it does not need

186 | a library layer. Let's see how this application would look like written

187 | with a BSD socket API. First, a TCP listener should bind to a port, and

188 | for every connected client, spawn a new thread that would handle it. A thread

189 | function that sends/receives data, looks something like this:

190 |

191 | ```c

192 | void handle_new_connection(int sock) {

193 | char buf[20];

194 | for (;;) {

195 | ssize_t len = recv(sock, buf, sizeof(buf), 0); // Receive data from remote

196 | if (len <= 0) break; // Error! Exit the loop

197 | send(sock, buf, len); // Success. Echo data back

198 | }

199 | close(sock); // Close socket, stop thread

200 | }

201 | ```

202 |

203 | Note that `recv()` function blocks until it receives some data from the client.

204 | Then, `send()` also blocks until is sends requested data back to the client.

205 | That means that this code cannot run in a bare metal implementation, because

206 | `recv()` would block the whole firmware. For this to work, an RTOS is required.

207 | A TCP/IP stack should run in a separate RTOS task, and both `send()` and

208 | `recv()` functions are implemented using an RTOS queue API, providing a

209 | blocking way to pass data from one task to another. Overall, this is how an

210 | embedded receive path looks like with socket API:

211 |

212 |

213 |

214 | The `send()` part would work in the reverse direction. Note that this approach

215 | requires TCP/IP stack implement data buffering for each socket, because

216 | an application consumes received data not immediately, but after some time,

217 | when RTOS queue delivers data. Note that using non-blocking sockets and

218 | `select()/poll()` changes things that instead of many application tasks,

219 | there is only one application task, but the mechanism stays the same.

220 |

221 | Therefore this approach with socket API has

222 | the following major characteristics:

223 |

224 | 1. It uses queues for exchanging data between TCP/IP stack and

225 | application tasks, which consumes both RAM and time

226 | 2. TCP/IP stack buffers received and sent data for each socket. Note that

227 | the app/library layer may also buffer data - for example, buffering a full

228 | HTTP request before it can be processed. So the same data goes through

229 | two buffering "zones" - TCP/IP stack, and library/app

230 |

231 | That means, socket API implementation takes extra time for data to be processed,

232 | and takes extra RAM for double-buffering in the TCP/IP stack.

233 |

234 | ### TCP echo server with non-socket (callback) API

235 |

236 | Now let's see how the same approach works without BSD socket API. Several

237 | implementations, including lwIP and Mongoose Library, provide callback API to

238 | the TCP/IP stack. Here is how TCP echo server would look like written using

239 | Mongoose API:

240 |

241 | ```c

242 | // This callback function is called for various network events, MG_EV_*

243 | void event_handler(struct mg_connection *c, int ev, void *ev_data, void *fn_data) {

244 | if (ev == MG_EV_READ) {

245 | // MG_EV_READ means that new data got buffered in the c->recv buffer

246 | mg_send(c, c->recv.buf, c->recv.len); // Send back the data we received

247 | c->recv.len = 0; // Discard received data

248 | }

249 | }

250 | ```

251 |

252 | In this case, all functions are non-blocking, that means that data exchange

253 | between TCP/IP stack and an app can be implemented via direct function calls.

254 | This is how receive path looks like:

255 |

256 |

257 |

258 | As you can see, in this case TCP/IP stack provides a callback API which

259 | a library or application layer can use to receive data directly. No need

260 | to send it over a queue. A library/app layer can buffer data, and that's

261 | the only place where buffering takes place. This approach wins for

262 | memory usage and performance. A firmware developer should use

263 | a proprietary callback API instead of BSD socket API.

264 |

265 | lwIP TCP/IP stack, for example, provides both socket and non-socket (raw) API,

266 | and raw API is more efficient in terms of RAM and performance. However

267 | developers rarely use raw API, because it is not trivial to understand and use

268 | compared to the socket API. The API of the Mongoose Library shown above

269 | is designed to be simple and easy to understand. API design can make things

270 | very easy or very difficult, so it is important to have a good API.

271 |

272 | ## Implementing layers 1,2,3 - making ping work

273 |

274 | ### Development environment and tools

275 |

276 | Now let's make our hands dirty and implement a working network stack on

277 | a microcontroller board. I will be using

278 | [Mongoose Library](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose) for all examples

279 | further on, for the following reasons:

280 |

281 | - Mongoose is very easy to integrate: just by copying two files,

282 | [mongoose.c]() and [mongoose.h]()

283 | - Mongoose has a built-in drivers, TCP/IP stack, HTTP/MQTT/Websocket library,

284 | and TLS 1.3 all in one, so it does not need any other software to create

285 | a network-enabled application

286 | - Mongoose provides a simple, polished callback API designed specifically

287 | for embedded developers

288 |

289 | The diagram below shows Mongoose architecture. As you can see, Mongoose can

290 | use external TCP/IP stack and TLS libraries, as well as built-in ones. In the

291 | following example, we are going to use only a built-in functionality, so we

292 | won't need any other software.

293 |

294 |

295 |

296 | All source code in this guide is MIT licensed, however Mongoose

297 | is licensed under a dual GPLv2/commercial license.

298 | I will be using a Nucleo board from ST Microelectronics, and there are several choices for the

299 | development environment:

300 | - Use Cube IDE provided by ST: [install Cube](https://www.st.com/en/development-tools/stm32cubeide.html)

301 | - Use Keil from ARM: [install Keil](https://www.keil.com/)

302 | - Use make + GCC compiler, no IDE: follow [this guide](https://mongoose.ws/documentation/tutorials/tools/)

303 |

304 | Here, I am going to use Cube IDE. In the templates, however, both Keil and

305 | make examples are provided, too. So, in order to proceed, install Cube IDE

306 | on your workstation, and plug in Nucleo board to your workstation.

307 |

308 | ### Skeleton firmware

309 |

310 | Note: this and the following sections has a Youtube helper video recorded:

311 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lKYM4b8TZts

312 |

313 | The first step would be to create a minimal, skeleton firmware that does

314 | nothing but logs messages to the serial console. Once we've done that, we'll

315 | add networking functionality on top of it. The table below summarises

316 | peripherals for various boards:

317 |

318 |

319 | | Board | UART, TX, RX | Ethernet | LED |

320 | | ---------------- | --------------- | ------------------------------------- | -------------- |

321 | | STM32H747I-DISCO | USART1, A9, A10 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, G12, G11, G13 | I12, I13, I14 |

322 | | STM32H573I-DK | USART1, A9, A10 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, G12, G11, G13 | I8, I9, F1 |

323 | | Nucleo-H743ZI | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, E1, B14 |

324 | | Nucleo-H723ZG | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, E1, B14 |

325 | | Nucleo-H563ZI | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B15, G11, G13 | B0, F4, G4 |

326 | | Nucleo-F746ZG | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, B7, B14 |

327 | | Nucleo-F756ZG | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, B7, B14 |

328 | | Nucleo-F429ZI | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, B7, B14 |

329 |

330 | **Step 1.** Start Cube IDE. Choose File / New / STM32 project

331 | **Step 2.** In the "part number" field, type the microcontroller name,

332 | for example "H743ZI". That should narrow down

333 | the MCU/MPU list selection in the bottom right corner to a single row.

334 | Click on the row at the bottom right, then click on the Next button

335 | **Step 3.** In the project name field, type any name, click Finish.

336 | Answer "yes" if a pop-up dialog appears

337 | **Step 4.** A configuration window appears. Click on Clock configuration tab.

338 | Find a field with a system clock value. Type the maximum value, hit enter,

339 | answer "yes" on auto-configuration question, wait until configured

340 | **Step 5.** Switch to the Pinout tab, Connectivity, then enable the UART controller

341 | and pins (see table above), choose "Asynchronous mode"

342 | **Step 6.** Click on Connectivity / ETH, Choose Mode / RMII, verify that the

343 | configured pins are like in the table above - if not, change pins

344 | **Step 7.** Lookup the LED GPIO from the peripherals table, and configure it

345 | for output. Click on the corresponding pin, select "GPIO output"

346 | **Step 8.** Click Ctrl+S to save the configuration. This generates the code

347 | and opens main.c file

348 | **Step 9.** Navigate to the `main()` function and add some logging to the

349 | `while` loop. Make sure to insert your code between the "USER CODE" comments,

350 | because CubeIDE will preserve it during code regeneration:

351 | ```c

352 | /* USER CODE BEGIN WHILE */

353 | while (1)

354 | {

355 | printf("Tick: %lu\r\n", HAL_GetTick());

356 | HAL_Delay(500);

357 | ```

358 | **Step 10.** Redirect `printf()` to the UART. Note the UART global variable

359 | generated by Cube at the beginning of `main.c` - typically it is

360 | `UART_HandleTypeDef huart3;`. Copy it, open `syscalls.c`, find function

361 | `_write()` and modify it the following way :

362 | ```c

363 | #include "main.h"

364 |

365 | __attribute__((weak)) int _write(int file, char *ptr, int len) {

366 | if (file == 1 || file == 2) {

367 | extern UART_HandleTypeDef huart3;

368 | HAL_UART_Transmit(&huart3, (unsigned char *) ptr, len, 999);

369 | }

370 | return len;

371 | }

372 | ```

373 | **Step 11.** Click on "Run" button to flash this firmware to the board.

374 | **Step 12.** Attach a serial monitor tool (e.g. putty on Windows, or

375 | `cu -l COMPORT -s 115200` on Mac/Linux) and observe UART logs:

376 | ```

377 | Tick: 90358

378 | Tick: 90860

379 | ...

380 | ```

381 | Our skeleton firmware is ready!

382 |

383 | ### Integrate Mongoose

384 |

385 | Now it's time to implement a functional TCP/IP stack. We'll use Mongoose

386 | Library for that. To integrate it, we need to copy two files into our source tree.

387 |

388 | **Step 1**. Open https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose in your browser, click on "mongoose.h". Click on "Raw" button, and copy file contents into clipboard.

389 | In the CubeIDE, right click on Core/Inc, choose New/File in the menu, type

390 | "mongoose.h", paste the file content and save.

391 | **Step 2**. Repeat for "mongoose.c". On Github, copy `mongoose.c` contents

392 | to the clipboard. In the CubeIDE, right click on Core/Src, choose New/File

393 | in the menu, type "mongoose.c", paste the file content and save.

394 | **Step 3**. Right click on Core/Inc, choose New/File in the menu, type

395 | "mongoose_custom.h", and paste the following contents:

396 | ```c

397 | #pragma once

398 |

399 | // See https://mongoose.ws/documentation/#build-options

400 | #define MG_ARCH MG_ARCH_NEWLIB

401 |

402 | #define MG_ENABLE_TCPIP 1 // Enables built-in TCP/IP stack

403 | #define MG_ENABLE_CUSTOM_MILLIS 1 // We must implement mg_millis()

404 | #define MG_ENABLE_DRIVER_STM32H 1 // On STM32Fxx series, use MG_ENABLE_DRIVER_STM32F

405 | ```

406 | **Step 4**. Implement Layer 1 (driver), 2 (TCP/IP stack) and 3 (library) in

407 | our code. Open `main.c`. Add `#include "mongoose.h"` at the top:

408 | ```c

409 | /* USER CODE BEGIN Includes */

410 | #include "mongoose.h"

411 | /* USER CODE END Includes */

412 | ```

413 | **Step 5**. Before `main()`, define function `mg_millis()` that returns

414 | an uptime in milliseconds. It will be used by Mongoose Library for the time

415 | keeping:

416 | ```c

417 | /* USER CODE BEGIN 0 */

418 | uint64_t mg_millis(void) {

419 | return HAL_GetTick();

420 | }

421 | /* USER CODE END 0 */

422 | ```

423 | **Step 6**. Navigate to `main()` function and change the code around `while`

424 | loop this way:

425 | ```c

426 | /* USER CODE BEGIN WHILE */

427 | struct mg_mgr mgr;

428 | mg_mgr_init(&mgr);

429 | mg_log_set(MG_LL_DEBUG);

430 |

431 | // On STM32Fxx, use _stm32f suffix instead of _stm32h

432 | struct mg_tcpip_driver_stm32h_data driver_data = {.mdc_cr = 4};

433 | struct mg_tcpip_if mif = {.mac = {2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7},

434 | // Uncomment below for static configuration:

435 | // .ip = mg_htonl(MG_U32(192, 168, 0, 223)),

436 | // .mask = mg_htonl(MG_U32(255, 255, 255, 0)),

437 | // .gw = mg_htonl(MG_U32(192, 168, 0, 1)),

438 | .driver = &mg_tcpip_driver_stm32h,

439 | .driver_data = &driver_data};

440 | NVIC_EnableIRQ(ETH_IRQn);

441 | mg_tcpip_init(&mgr, &mif);

442 |

443 | while (1) {

444 | mg_mgr_poll(&mgr, 0);

445 | /* USER CODE END WHILE */

446 | ```

447 |

448 | **Step 7**. Connect your board to the Ethernet. Flash firmware. In the serial

449 | log, you should see something like this:

450 | ```

451 | bb8 3 mongoose.c:14914:mg_tcpip_driv Link is 100M full-duplex

452 | bbd 1 mongoose.c:4676:onstatechange Link up

453 | bc2 3 mongoose.c:4776:tx_dhcp_discov DHCP discover sent. Our MAC: 02:03:04:05:06:07

454 | c0e 3 mongoose.c:4755:tx_dhcp_reques DHCP req sent

455 | c13 2 mongoose.c:4882:rx_dhcp_client Lease: 86400 sec (86403)

456 | c19 2 mongoose.c:4671:onstatechange READY, IP: 192.168.2.76

457 | c1e 2 mongoose.c:4672:onstatechange GW: 192.168.2.1

458 | c24 2 mongoose.c:4673:onstatechange MAC: 02:03:04:05:06:07

459 | ```

460 | If you don't, and see DHCP requests message like this:

461 | ```

462 | 130b0 3 mongoose.c:4776:tx_dhcp_discov DHCP discover sent. Our MAC: 02:03:04:05:06:07

463 | 13498 3 mongoose.c:4776:tx_dhcp_discov DHCP discover sent. Our MAC: 02:03:04:05:06:07

464 | ...

465 | ```

466 | The most common cause for this is you have your Ethernet pins wrong. Click

467 | on the `.ioc` file, go to the Ethernet configuration, and double-check the

468 | Ethernet pins against the table above.

469 |

470 | **Step 8**. Open terminal/command prompt, and run a `ping` command against

471 | the IP address of your board:

472 | ```sh

473 | $ ping 192.168.2.76

474 | PING 192.168.2.76 (192.168.2.76): 56 data bytes

475 | 64 bytes from 192.168.2.76: icmp_seq=0 ttl=64 time=9.515 ms

476 | 64 bytes from 192.168.2.76: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=1.012 ms

477 | ```

478 |

479 | Now, we have a functional network stack running on our board. Layers 1,2,3

480 | are implemented. It's time to create an application - a simple web server,

481 | hence implement layer 4.

482 |

483 | ## Implementing layer 4 - a simple web server

484 |

485 | Let's add a very simple web server that responds "ok" to any HTTP request.

486 |

487 | **Step 1**. After the `mg_tcpip_init()` call, add this line that creates HTTP listener

488 | with `fn` event handler function:

489 | ```c

490 | mg_http_listen(&mgr, "http://0.0.0.0:80", fn, NULL);

491 | ```

492 | **Step 2**. Before the `mg_millis()` function, add the `fn` event handler function:

493 | ```c

494 | static void fn(struct mg_connection *c, int ev, void *ev_data) {

495 | if (ev == MG_EV_HTTP_MSG) {

496 | struct mg_http_message *hm = ev_data; // Parsed HTTP request

497 | mg_http_reply(c, 200, "", "ok\r\n");

498 | }

499 | }

500 | ```

501 | That's it! Flash the firmware. Open your browser, type board's IP address and

502 | see the "ok" message.

503 |

504 | Note that the [mg_http_reply()](https://mongoose.ws/documentation/#mg_http_reply)

505 | function is very versatile: it cat create formatted output, like printf

506 | on steroids. See [mg_snprintf()](https://mongoose.ws/documentation/#mg_snprintf-mg_vsnprintf)

507 | for the supported format specifiers: most of them are standard printf, but

508 | there are two non-standard: `%m` and `%M` that accept custom formatting

509 | function - and this way, Mongoose's printf can print virtually anything.

510 | For example, JSON strings. That said, with the aid of `mg_http_reply()`,

511 | we can generate HTTP responses of arbitrary complexity.

512 |

513 | So, how the whole flow works? Here is how. When a browser connects,

514 | an Ethernet IRQ handler (layer 1) kicks in. It is defined by Mongoose, and activated by

515 | the `#define MG_ENABLE_DRIVER_STM32H 1` line in the `mongoose_custom.h`: [ETH_IRQHandler](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/drivers/stm32h.c#L252). Other environments, like CubeIDE, implement `ETH_IRQHandler`

516 | and activate it when you select "Enable Ethernet interrupt" in the Ethernet

517 | configuration. To avoid clash with Cube, we did not activate Ethernet interrupt.

518 |

519 | IRQ handler reads frame from the DMA, copies that frame to the Mongoose's

520 | [receive queue](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/net_builtin.h#L30), and exits.

521 | That receive queue is special, it is a thread-safe

522 | single-producer-single-consumer non-blocking queue, so an IRQ handler, being

523 | executed in any context, can safely write to it.

524 |

525 | The `mg_poll()` function in the infinite `while()` loop constantly

526 | verifies, whether we receive any data in the receive queue. When it detects

527 | a frame in the receive queue, it extracts that frame, passes it on to the

528 | [mg_tcp_rx()](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/net_builtin.c#L800) function - which is an etry point to the layer 2 TCP/IP stack.

529 |

530 |

531 | That `mg_tcp_rx()` function parses headers, starting from Ethernet header,

532 | and when it detects that a received frame belongs to one of the Mongoose

533 | TCP or UDP connections, it copies frame payload to the connection's `c->recv`

534 | buffer and [calls `MG_EV_READ` event](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/net_builtin.c#L687).

535 |

536 |

537 | At this point, processing leaves layer 2 and enters layer 3 - a library layer.

538 | Mongoose's HTTP event handlers catches `MG_EV_READ`, parses received data,

539 | and when it detects that the full HTTP message is buffered, it [sends the

540 | `MG_EV_HTTP_MSG` with parsed HTTP message](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/http.c#L1033) to the application - layer 4.

541 |

542 | And this is where our event handler function `fn()` gets called. Our code is

543 | simple - we catch `MG_EV_HTTP_MSG` event, and use Mongoose's API function

544 | `mg_http_reply()` to craft a simple HTTP response:

545 | ```

546 | HTTP/1.1 200 OK

547 | Content-Length: 4

548 |

549 | ok

550 | ```

551 |

552 | This response goes to Mongoose's `c->send` output buffer, and `mg_mgr_poll()`

553 | drains that data to the browser, [splitting the response by frames](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/net_builtin.c#L587-L588)

554 | in layer 2, then passing to the layer 1. An Ethernet driver's output function [mg_tcpip_driver_stm32h_tx()](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/drivers/stm32h.c#L208) sends those frames back to the browser.

555 |

556 | This is how Mongoose Library works.

557 |

558 | Other implementations, like Zephyr, Amazon FreeRTOS-TCP, Azure, lwIP, work in

559 | a similar way. They implement BSD socket layer so it is a bit more complicated

560 | cause it includes an extra socket layer, but the principle is the same.

561 |

562 | ## Implementing Web UI

563 |

564 | Using `mg_http_reply()` function is nice, but it's very good for creating

565 | custom responses. It is not suitable for serving files. And the standard way

566 | to build a web UI is to split it into two parts:

567 | - a static part, which consists of directory with `index.html`, CSS,

568 | JavaScript and image files,

569 | - a dynamic part, which serves REST API

570 |

571 | So instead of using `mg_http_reply()` and responding with "ok" to any request,

572 | let's create a directory with `index.html` file and serve that directory.

573 | Mongoose has API function `mg_http_serve_dir()` for that. Let's change the

574 | event handler code to use that function:

575 |

576 | ```c

577 | static void fn(struct mg_connection *c, int ev, void *ev_data) {

578 | if (ev == MG_EV_HTTP_MSG) {

579 | struct mg_http_message *hm = ev_data; // Parsed HTTP request

580 | struct mg_http_serve_opts opts = {.root_dir = "/web_root"};

581 | mg_http_serve_dir(c, hm, &opts);

582 | }

583 | }

584 | ```

585 |

586 | Build it and get build error "undefined reference to 'mkdir'". This is because

587 | `mg_http_serve_dir()` function tries to use a default POSIX filesystem to

588 | read files from directory `/web_root`, and our firmware does not have support

589 | for the POSIX filesystem.

590 |

591 | What are the possibilities here? First, we can implement POSIX filesystem,

592 | by using an internal or external flash memory. Then we can copy our `web_root`

593 | directory there, and our code will start to work. This is the hard way.

594 |

595 | The easy way is to use a so-called embedded filesystem, by

596 | transforming all files in the web directory into C arrays, and compiling them

597 | into the firmware binary. This way, all UI files are simply hardcoded into the

598 | firmware binary, and there is no need to implement a "real" filesystem:

599 |

600 | **Step 1**. Tell `mg_http_serve_dir()` to use packed filesystem:

601 | ```c

602 | struct mg_http_serve_opts opts = {.root_dir = "/web_root", .fs = &mg_fs_packed};

603 | ```

604 | **Step 2**. Enable packed filesystem, and disable POSIX filesystem in `mongoose_custom.h`:

605 | ```c

606 | #define MG_ENABLE_PACKED_FS 1

607 | #define MG_ENABLE_POSIX_FS 0

608 | ```

609 | **Step 3**. Create a new file `Core/Src/packed_fs.c`. Go to https://mongoose.ws/ui-pack/,

610 | review UI files. Copy/paste the contents of generated `packed_fs.c`, save.

611 |

612 | Build the firmware - and now it should build with no errors.

613 |

614 | Let's review what that UI packer does. As you can see, it has 3 files, which

615 | implement a very simple Web UI with LED control. The `index.html` file

616 | loads `main.js` file, which defines a button click handler. When a button

617 | gets clicked, it makes a request to the `api/led/toggle` URL, and when

618 | than request completes, it makes another request to `api/led/get` URL,

619 | and sets the status span element to the result of the request.

620 |

621 | The tool has a preview window, and if any of the files are changed,

622 | it automatically refreshes preview and regenerates packed_fs.c. The packed_fs.c

623 | is a simple C file, which contains three C arrays, representing three files

624 | we have, and two helper functions `mg_unlist()` and `mg_unpack()`, used by

625 | Mongoose:

626 | - the `mg_unlist()` function allows to scan the whole "filesystem" and get names of every file,

627 | - the `mg_unpack()` function returns file contents, size, and modification time for a given file.

628 |

629 | Mongoose provides a command line utility [pack.c](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/master/test/pack.c)

630 | to generate `packed_fs.c` automatically during the build. The example of that

631 | is a [Makefile](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/f883504d2d44d24cae1ca6c9f88ce780ab36f59b/examples/device-dashboard/Makefile#L38-L43)

632 | for device dashboard example in Mongoose repository, which not only packs,

633 | but also compresses files to minimise their size. But here, we'll use the

634 | web tool because it is visual and makes it easy to understand the flow.

635 |

636 | The static HTML is extremely simple. There 3 files: `index.html`, `style.css`

637 | and `main.js`. The `index.html` references, or loads, the other two:

638 |

639 | **index.html:**

640 | ```html

641 |

642 |

643 |

644 |

645 |

646 |

647 |

648 |

My Device

649 | LED status:

650 | 0

651 |

652 |

653 |

654 |

655 |

656 | ```

657 |

658 | **style.css:**

659 | ```css

660 | .main { margin: 1em; }

661 | #status { display: inline-block; width: 2em; }

662 | ```

663 |

664 | The Javascript code in the `main.js` file installs an event handler on button

665 | click, so when a user clicks on a button, JS code makes HTTP requests -

666 | I'll comment down below how it all works together:

667 |

668 | **main.js:**

669 | ```javascript

670 | var getStatus = ev => fetch('api/led/get')

671 | .then(r => r.json())

672 | .then(r => { document.getElementById('status').innerHTML = r; });

673 |

674 | var toggle = ev => fetch('api/led/toggle')

675 | .then(r => getStatus());

676 |

677 | document.getElementById('btn').onclick = toggle;

678 | ```

679 |

680 | Now, let's flash the firmware. Go to the IP address in the browser - and

681 | now we see the Web UI with a button! Click on the button, and see that nothing

682 | happens! The LED does not turn on and off. Open developer tools and see that

683 | on every click, a browser makes "toggle" and "get" requests which return 404

684 | error - not found. Let's implement those API calls.

685 |

686 | Change the event handler in the following way:

687 | ```c

688 | static void fn(struct mg_connection *c, int ev, void *ev_data) {

689 | if (ev == MG_EV_HTTP_MSG) {

690 | struct mg_http_message *hm = (struct mg_http_message *) ev_data;

691 | if (mg_http_match_uri(hm, "/api/led/get")) {

692 | mg_http_reply(c, 200, "", "%d\n", HAL_GPIO_ReadPin(GPIOB, GPIO_PIN_0));

693 | } else if (mg_http_match_uri(hm, "/api/led/toggle")) {

694 | HAL_GPIO_TogglePin(GPIOB, GPIO_PIN_0); // Can be different on your board

695 | mg_http_reply(c, 200, "", "true\n");

696 | } else {

697 | struct mg_http_serve_opts opts = {.root_dir = "/web_root", .fs = &mg_fs_packed};

698 | mg_http_serve_dir(c, hm, &opts);

699 | }

700 | }

701 | }

702 | ```

703 |

704 | Note the `mg_http_match_uri()` checks. There, we are making different responses

705 | to different URLs. On `/api/led/get` URL request, we're responding with

706 | LED status, and on `/api/led/toggle` request, we're toggling the pin and

707 | responding with `true`.

708 |

709 | Build and flash this firmware. Refresh the page in the browser. Click on the

710 | button - and now, LED toggle works! If we open developer tools in the browser,

711 | we can see the sequence of the network requests made by the browser.

712 |

713 |

714 |

715 | Below is the diagram of the interaction between the browser and the device,

716 | with explanations of every step:

717 |

718 |

719 |

720 | This is the flow for the Web UI of any complexity. Now, it is just a matter of

721 | creating a professional UI interface using any suitable JS/CSS framework, and

722 | extending the event handler function with the API calls that that UI invokes.

723 | That's all it takes.

724 |

725 | ## Implementing Device Dashboard

726 |

727 | Let me show you how to repeat everything we did in Cube - in the make + GCC

728 | environment in one minute. Navigate to https://mongoose.ws/demo/?clear=1

729 | This simple web tool creates a make project completely in your browser.

730 | Choose the board, the "simple project". You can download the project to your

731 | workstation and build manually. But we'll build in a browser - click on Build

732 | button. That zips the projects and sends it to mongoose.ws site, which has

733 | ARM GCC pre-installed. It simply runs `make`, creates firmware binary, and

734 | sends that binary back to your browser. Now you can download that binary,

735 | or flash it directly from your browser.

736 |

737 | The "simple" project repeats what we've already done in Cube, with one

738 | important difference - it also implements TLS. In other words, it can serve

739 | both HTTP and HTTPS. Note that the binary size is less than 60 Kb! We will

740 | cover TLS later, as it needs a separate discussion.

741 |

742 | Now, let's click on "Start Over" button and build "Web UI Dashboard" project.

743 | It follows absolutely the same flow as "simple" project, just the Web UI is

744 | significantly more versatile, built with Preact JS framework and Tailwind CSS

745 | framework. The event handler function moved into a separate file, `net.c`,

746 | and supports many API calls required by Web UI - to show dashboard stats,

747 | settings, and firmware update. By the way, the firmware update is completely

748 | functional - but I won't cover it here, as it is a big topic on itself.

749 | I won't cover the process of static UI creation in React, as there are tons

750 | of very good tutorials on that. But if you want me to cover that, join our

751 | Discord server and let me know.

752 |

753 | What I'll do is to move that UI into the Cube project of ours.

754 |

755 | **Step 1.** Copy net.c, net.h, packed_fs.c into the Cube project

756 | **Step 2.** Add the following `include "net.h"` at the top of the main.c file

757 | **Step 3.** Comment out `mg_http_listen(...)` call, add `web_init()` call

758 | **Step 4.** Open net.h, modify HTTP_URL port 8000 to port 80

759 |

760 | Rebuild, reflash, refresh your browser. We have a functional versatile

761 | Web UI device dashboard reference running!

762 |

763 | ## Device management using MQTT protocol

764 |

765 |

766 | ## Enabling TLS

767 |

768 | ## Talking to AWS IoT and Microsoft Azure services

769 |

770 | ## About me

771 |

772 | I am Sergey Lyubka, an engineer and entrepreneur. I hold a MSc in Physics from

773 | Kyiv State University, Ukraine. I am a director and a co-founder at Cesanta - a

774 | technology company based in Dublin, Ireland. Cesanta develops embedded

775 | solutions:

776 |

777 | - https://mongoose.ws - an open source HTTP/MQTT/Websocket network library

778 | - https://vcon.io - a remote firmware update / serial monitor framework

779 |

780 | You are welcome to register for

781 | [my free webinar on embedded network programming](https://mongoose.ws/webinars/)

782 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------