├── README.md

├── design-patterns

└── REMAP_INCOMING_JSONS.md

├── introduction

├── CODE_QUALITY.md

├── ERRORS.md

├── FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING.md

├── INTRODUCTION.md

├── LOGGING.md

├── WHY_ELIXIR.md

└── WORKING_IN_A_TEAM.md

├── labs

├── calc

│ ├── .gitignore

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── config

│ │ └── config.exs

│ ├── lib

│ │ ├── calc.ex

│ │ └── operation.ex

│ ├── mix.exs

│ └── test

│ │ ├── calc_test.exs

│ │ └── test_helper.exs

└── ninety_nine

│ ├── .formatter.exs

│ ├── .gitignore

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── config

│ └── config.exs

│ ├── lib

│ ├── ninety_nine.ex

│ ├── p1.ex

│ ├── p2.ex

│ ├── p3.ex

│ ├── p4.ex

│ ├── p5.ex

│ └── p6.ex

│ ├── mix.exs

│ └── test

│ ├── ninety_nine_test.exs

│ └── test_helper.exs

└── references

├── docker

└── DOCKER.md

├── elixir

├── ARCHITECTURE.md

├── CLOSURES.md

├── DEBUGGING.md

├── DOCUMENTATION.md

├── ELIXIR.md

├── ERROR_HANDLING.md

├── FUNCTION_APPLICATION.md

├── MONITORING.md

├── PATTERN-MATCHING.md

├── PIPES.md

├── SPECS.md

├── WITH.md

└── images

│ ├── atom-naming.png

│ ├── module-naming.png

│ └── variable-naming.png

├── git

├── GIT.md

└── git-model.png

├── http

├── CURL.md

├── HTTP.md

├── REST.md

└── http-headers-status-v3.png

├── linux

├── LINUX.md

├── REGEX.md

├── VIM.md

└── vim.gif

├── markdown

└── MARKDOWN.md

├── phoenix

├── CONN.md

├── CONTROLLERS.md

├── PHOENIX.md

├── PLUG.md

└── ecto

│ ├── ECTO.md

│ ├── MIGRATIONS.md

│ └── MULTI.md

├── postgres

└── POSTGRES.md

├── semiotics

└── SEMIOTICS.md

└── typing

├── TYPING.md

└── typing-fingers.png

/README.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Elixir in a Team

2 | ================

3 |

4 | > "Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand." — Martin Fowler

5 |

6 | Well, you just arrived in a company to work with Elixir, but wait, there are a

7 | lot of resources needed, behind coding! And the most important of all, is to

8 | learn to code for your team. People will need to read your code, typing is

9 | essential to leave your brain CPU resources focus on coding, instead of hunting

10 | letters, code-style, architecture, HTTP, git, linux, and much more.

11 |

12 | But the most important issue: you take some vacations, and your co-workers will

13 | open and read/mantain your code... oho... what happens now ? can they understand

14 | something ? can they compile ? can they change some part of the code with safety,

15 | or they become afraid of touching it ? It's all about coding for

16 | others, and once you understand that well, for sure your approach in coding will be

17 | the correct one, and your code will be a real aggregated value for your company.

18 |

19 | An excelent reference for Elixir is in [Elixir

20 | School](https://elixirschool.com/en/). I added in this repo a lot of info on how

21 | to write code for you team, enjoy.

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 | ## Introduction

26 |

27 | * [introduction](introduction/INTRODUCTION.md) - some theory to start

28 | * [why-elixir](introduction/WHY_ELIXIR.md) - good reasons to adopt

29 | * [working-in-a-team](introduction/TEAM.md) - what is the approach on learning

30 | how to code for people

31 | * [functional-programming](introduction/FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING.md) -

32 | introduction and basic principles for functional programming

33 |

34 |

35 | ## References

36 |

37 |

38 | ### Elixir

39 | * [quick-reference](references/elixir/ELIXIR.md) - amazing quick reference.

40 | * [specs](references/elixir/SPECS.md) - type specifications for your functions.

41 | * [error-handling](references/elixir/ERROR_HANDLING.md) - many good strategies

42 | * [with](references/elixir/WITH.md) - pipelines using {:ok, res} and {:error, message} pattern matchings

43 | * [pipes](references/elixir/PIPES.md) - many options on how to use them

44 | * [debugging](references/elixir/DEBUGGING.md) - local and remote debugging techniques

45 | * [monitoring](references/elixir/MONITORING.md) - metrics collection,

46 | application monitoring, tracing and profiling, and exception monitoring.

47 | * [documentation](references/elixir/DOCUMENTATION.md) - writing documentation

48 | * [pattern-matching](references/elixir/PATTERN-MATCHING.md) - big advantages !

49 | * TODO: [boilerplate](references/BOILERPLATE.md) - essential dependencies: ex_doc, dialyzer, sentry, docker, etc...

50 | * TODO: http://www.jeramysingleton.com/phoenix-templates-are-just-functions/

51 |

52 | ### Phoenix / Ecto

53 |

54 | * [conn](references/phoenix/CONN.md) - http data structure

55 | * [controllers](references/phoenix/CONTROLLERS.md) - design patterns in

56 | controllers

57 | * [plug](references/phoenix/PLUG.md) - building components to http calls

58 | * [multi](references/phoenix/ecto/MULTI.md) - multi with examples on cross

59 | * [migrations](references/phoenix/ecto/MIGRATIONS.md) - migrations cheat sheet

60 |

61 |

62 |

63 | ### GIT

64 | * [git](references/git/GIT.md) - code repository to share code with a team

65 |

66 | ### Semiotics

67 | * [overview](references/semiotics/SEMIOTICS.md) - it's all is about

68 | communication

69 |

70 | ### Postgres

71 | * [postgres](references/postgres/POSTGRES.md) - Tutorials, tips, etc...

72 |

73 | ### Typing

74 |

75 | * [typing](references/typing/TYPING.md) - finger positions and links

76 |

77 |

78 | ### Linux

79 | * [linux](references/linux/LINUX.md) - linux

80 | * [regex](references/linux/REGEX.md) - regex tutorial and references

81 | * [vi](references/linux/VIM.md) - vi, the super hero editor

82 |

83 | ### HTTP

84 | * [http](references/http/HTTP.md) - hyper text transfer protocol introduction

85 | * [curl](references/http/CURL.md) - making http requests from the command line

86 | * [rest](references/http/REST.md) - basic and advanced concepts on building a

87 | REST API

88 |

89 | ### Deploy

90 | * TODO: [docker](references/docker/DOCKER.md) - building containers

91 | * TODO: [kubernetes](references/kubernetes/KUBERNETES.md) - sending your app to the

92 | cloud

93 |

94 |

95 | ## Labs

96 |

97 | * [calc](labs/calc) - simple calculations, using a datastructure to store every

98 | step

99 | * [ninety-nine](labs/ninety_nine) - different solutions for the

100 | [99-functional-problems](http://www.ic.unicamp.br/~meidanis/courses/mc336/2009s2/prolog/problemas/)

101 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/design-patterns/REMAP_INCOMING_JSONS.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Remaping Incoming Jsons

2 | =======================

3 |

4 |

5 | Sometimes you have to maintain your legacy API, but internally you would love

6 | to use beautiful and meaninful names. For that, an amazing solution is to add

7 | a small function plug in the incoming controller. Why not a complete plug in

8 | the router path ? because not all calls need to be remaped, and you also want

9 | to maintain your mapping solution in the place the incoming parameters are

10 | arriving, for the sake of design and also performance. Let's see the

11 | example below, on how to translate the JSON keys.

12 |

13 | In your web file, where phoenix automatically create the quote to introduce

14 | needed imports for the controller, add the translate_key function. I added

15 | some docs, but when doing meta-programming, we generally leave them away.

16 |

17 | ```elixir

18 |

19 | def controller do

20 | quote do

21 | use Phoenix.Controller, namespace: BackWeb

22 | import Plug.Conn

23 | import BackWeb.Router.Helpers

24 | import BackWeb.Gettext

25 | @doc """

26 | Sometimes, the API call comes with a different key name on the attribute data structure.

27 | For example, http://my_server:4000/?lang , but on the db, the field 'language' is called

28 | key_lan. This functions is aimmed to translate when the data structure arrives in the

29 | schema file, inside contexts. To send out translations, we change in the 'view' render

30 | file, related to that json output. You will be happy to have all your params aligned

31 | with the database schema names :)

32 |

33 | iex> Back.Helpers.translate_key(%{a: 1, b: 2, c: 3}, :b, :z)

34 | %{a: 1, z: 2, c: 3}

35 | """

36 | @spec translate_key(map(), String.t(), String.t()) :: map()

37 | def translate_key(attrs, source_key, target_key) do

38 | attrs

39 | |> Map.put(target_key, attrs[source_key])

40 | |> Map.drop([source_key])

41 | end

42 | @type controller_error :: nil | {:error, Ecto.Changeset.t()}

43 | end

44 | end

45 |

46 | ```

47 |

48 | In your controller, add

49 |

50 | ```

51 | plug :translate

52 | ```

53 |

54 | On the end of your controller file, add:

55 |

56 |

57 | ```elixir

58 | def translate(%{params: params} = conn, _), do:

59 | %{conn | params: translate_key(params, "class", "type")}

60 | ```

61 |

62 | Amazing, your controller can translate all the JSON calls like

63 | {"class":"some_data_here"} to {"type":"some_data_here"}.

64 |

65 | See how elegant, all the controller calls will received the transformed call,

66 | before they arrive in the actual controller function.

67 |

68 |

69 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/introduction/CODE_QUALITY.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Code Quality

2 | ============

3 |

4 |

5 | ## Follow a Style

6 |

7 | The codebase you’re working on needs to have a consistent style. If you’re part of a team then get together to establish a set of guidelines to work from. Simplify the effort by using existing styles in the community. Here are a few general points to keep in mind:

8 |

9 | Use informative names for variables, functions, and classes. There is no reason to be clever or sly by naming things with a small handful of characters.

10 | Don’t cram all your code within a couple of source files. Break your code into pieces where it makes sense.

11 | At the same time, don’t create functions that do 20 different things. Keep functions focused on a particular… function.

12 | Remain consistent with whitespace, naming, commenting, and the other rules you establish.

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 | ##

17 |

18 |

19 | * [quality-code-in-erlang](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQyt9Vlkbis) - how to

20 | transform a big spagetti function in well and clearly diveded ones

21 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/introduction/ERRORS.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Errors

2 | ======

3 |

4 |

5 | Use LOGs only to detect software malfunction, all the business exceptions should be part of the main system, and audited.

6 |

7 | If {error, reason} is something you need to handle in your business logic you deal with it with pattern matching and you should only deal with the errors you care about. Because it is part of business logic you have to deal with is so the "complexity" is unavoidable.

8 |

9 | Don't catch errors and log anywhere except the top level of your code. It is better to bubble up. Error messages should ideally be tuples of atoms with as much information as possible so that you clearly know which sort of errors to handle and which to ignore.

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 | * actionable errors - i.e. expected errors. When those happen we need to handle them gracefully, so that our application can continue working correctly. A good example of this is invalid data provided by the user or data not present in the database. In general we want to handle this kind of errors by using tuple return values ({:ok, value} | {:error, reason}) - the consumer can match on the value and act on the result.

14 |

15 | * fatal errors - errors that place our application in undefined state - violate some system invariant, or make us reach a point of no return in some other way. A good example of this is a required config file not present or a network failing in the middle of transmitting a packet. With that kind of errors we usually want to crash and lean on the supervision system to recover - we handle all errors of this kind in a unified way. That’s exactly what the let it crash philosophy is about - it’s not about letting our application burn in case of any errors, but avoiding excessive code for handling errors that can’t be handled gracefully. You can read more about what the “let it crash” means in the excellent article by Fred Hebert of the “Learn You Some Erlang for Great Good” fame - “The Zen of Erlang”.

16 |

17 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/introduction/FUNCTIONAL_PROGRAMMING.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Functional Programming

2 | ======================

3 |

4 | ## Basic

5 |

6 |

7 | * https://medium.com/making-internets/functional-programming-elixir-pt-1-the-basics-bd3ce8d68f1b

8 |

9 |

10 | ## Advanced

11 |

12 | * [try-haskell](http://tryhaskell.org/) - because haskell is a pure functional

13 | programming, and maybe you come from OO world, you will need a wash brain...

14 | or even change your brain, and Haskell comes to save

15 |

16 | * [learn-you-a-haskell](http://learnyouahaskell.com) - amazing book to help you

17 | understand FP... a real wash-brain for OO devs... please, don't try to learn

18 | Scala and move slowly, unless you are fine to have a spaghetti paradigm in

19 | you code.

20 |

21 | * [future-learn](https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/functional-programming-haskell)

22 | - seems to be an excellent course

23 |

24 | * [the-most-adequate-guide](https://github.com/MostlyAdequate/mostly-adequate-guide)

25 | - if you would love to code FP in javascript this guide is a must. Also very

26 | good to understand the concepts.

27 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/introduction/INTRODUCTION.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 | Even bad code can function. But if code isn’t clean, it can bring a development organization to its knees. Every year, countless hours and significant resources are lost because of poorly written code. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/introduction/LOGGING.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Logging

2 | =======

3 |

4 |

5 | * Diagnostic logging: has been discussed by others already and I won't belabor the point much more. I'll just say you should strongly think about what happens if there's a log failure? Do you care enough to throw an exception up through the app or manage it another way? This is an "it depends" but logging info level messages probably should be skipped. That is the diagnostic part of logging, the most important one and basically the one that developers could understand easier, as it is more part of their daily work routine. The diagnostic logging takes care of recording the events that happen during runtime ( method calls, input/outputs, HTTP calls, SQL executions )

6 |

7 | * Audit logging: is a business requirement. Audit logging captures significant events in the system and are what management and the legal eagles are interested in. This is things like who signed off on something, who did what edits, etc. As a sysadmin or developer troubleshooting the system, you're probably only mildly interested in these. However, in many cases this kind of logging is absolutely part of the transaction and should fail the whole transaction if it can't be completed. The audit logging is responsible for recording more abstract, business logic events. Such events can be user actions (adding/editing/removal of content, transactions, access data) or other things that have either managerial value or, more importantly, legal value. Special attention on keeping the state on the central database, so you can officially track them for compliance, and also create code to react to business events, something that you couldn't achieve if you simply throw the information to an external text file.

8 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/introduction/WHY_ELIXIR.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Why Elixir

2 | ==========

3 |

4 | We have been in San Francisco, and it's amazing how people there are moving from

5 | Rails to Elixir! Yeah!. See

6 | [how](https://medium.com/@elviovicosa/5-reasons-you-should-use-phoenix-instead-of-rails-in-your-next-project-504b4d83c48e)

7 | people are talking about it.

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 | ## Declarative, instead of Imperative

13 |

14 | Elixir is better for declarative programming, but you should pay attention to

15 | make your code declarative anyway.

16 |

17 | *Imperative programming*: telling the “machine” how to do something, and as a result what you want to happen will happen.

18 |

19 | *Declarative programming*: telling the “machine” what you would like to happen, and letting the computer figure out how to do it.

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 | ```javascript

24 | 'use strict'

25 |

26 | const sumAllMultiples = limit => {

27 | let sum = 0

28 |

29 | for(let i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

30 | if(i % 3 == 0 || i % 5 == 0) {

31 | sum += i;

32 | }

33 | }

34 | return sum;

35 | }

36 |

37 | console.log(sumAllMultiples(1000));

38 | ```

39 |

40 |

41 | The same solution in Elixir

42 |

43 | ```elixir

44 | 1..999 |> Enum.to_list

45 | |> Enum.filter(&(rem(&1, 3) == 0 or rem(&1, 5) == 0))

46 | |> Enum.sum

47 | |> IO.puts

48 | ```

49 |

50 |

51 | ## Microservices in-the-box

52 | Instead of creating a new docker for every microservices, consuming tons of

53 | memory/CPU, and relying on external libs like

54 | [this](https://github.com/Netflix/conductor) made by Netflix, and other gigants,

55 | you can have all the power of microservice distribution with a "Visual Studio"

56 | monolith experience, with all the necessary tools in the box. If you are

57 | building a startup, for sure microservice architecture is the

58 | [wrong](https://hackernoon.com/if-youre-thinking-about-microservices-for-an-mvp-you-re-probably-doing-it-wrong-6fef8341fce4)

59 | option, but anyway, you feel and believe that in 2 years your new app will have

60 | some thousand of users, and you would like to be ready. So in Elixir you can

61 | start with the most simplicity (more than Java!), and have an in-the-box super

62 | scalability. The [cowboy](https://ninenines.eu) web-server is a dream server,

63 | think that every request receives its own process, in parallel... and you are

64 | done, a super simple nano-service architeture, ready to receive

65 | [millions](http://www.ostinelli.net/a-comparison-between-misultin-mochiweb-cowboy-nodejs-and-tornadoweb/)

66 | of requests. See

67 | [here](http://tjheeta.github.io/2016/12/16/dawn-of-the-microlith-monoservices-microservices-with-elixir/)

68 | a deep comparison between the Elixir BEAM machine vs Standard Microservices

69 | architcture.

70 |

71 |

72 | ## Actor based concurrency model

73 |

74 | Instead of mutex, semaphores, and much more complexity, actor based model is

75 | language native and light, very light. Many

76 | [libs](http://berb.github.io/diploma-thesis/original/054_actors.html) today are

77 | adding actor based concurrency model, but really farway from the Beam Machine,

78 | behind the Elixir/Erlang binary files, where garbage collector is per process,

79 | etc... that build a soft real time system.

80 |

81 |

82 | ## Real time scalability

83 | 2 million users connectect in the same server, using web-sockets, with near zero

84 | CPU usage, as described

85 | [here](http://phoenixframework.org/blog/the-road-to-2-million-websocket-connections).

86 |

87 |

88 | ## Code clarity and size

89 |

90 | "We’ve also seen an improvement in code clarity. We’re converting our

91 | notifications system from Java to Elixir. The Java version used an Actor system

92 | and weighed in at around 10,000 lines of code. The new Elixir system has shrunk

93 | this to around 1000 lines." . See

94 | [here](https://pragtob.wordpress.com/2017/07/26/choosing-elixir-for-the-code-not-the-performance/)

95 | for more details.

96 |

97 | ## Web framework

98 |

99 | You can use phoenix, that is an amazing framework for web and database. Because

100 | functional programming is so powerfull, you will get a simple code with a lot of

101 | power. See [here](https://www.slant.co/topics/362/~best-backend-web-frameworks)

102 | the comparison.

103 |

104 |

105 | ## Future oriented

106 |

107 | Joe Armstrong, creator of Erlang, said something along the lines of: "In OO, if you ask a banana, you might receive a banana with the gorilla and the jungle". When we encapsulate data and behaviour in an object, we have no idea about what is going on there. Of course, one might argue that good OO design might solve this problem. I agree to a certain degree since normally you don't have control over third-party libraries. See [here](https://janjiss.com/the-way-of-modern-web/) for more details.

108 |

109 |

110 |

111 |

112 |

113 |

114 | ## Big and successful companies use Elixir

115 | See

116 | [here](https://codesync.global/media/successful-companies-using-elixir-and-erlang/)

117 | and [here](https://www.netguru.co/blog/10-companies-use-elixir)

118 |

119 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/introduction/WORKING_IN_A_TEAM.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/henry-hz/elixir-in-a-team/92c00818ae96ff2889427b914769b521915754ad/introduction/WORKING_IN_A_TEAM.md

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/calc/.gitignore:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # The directory Mix will write compiled artifacts to.

2 | /_build/

3 |

4 | # If you run "mix test --cover", coverage assets end up here.

5 | /cover/

6 |

7 | # The directory Mix downloads your dependencies sources to.

8 | /deps/

9 |

10 | # Where 3rd-party dependencies like ExDoc output generated docs.

11 | /doc/

12 |

13 | # Ignore .fetch files in case you like to edit your project deps locally.

14 | /.fetch

15 |

16 | # If the VM crashes, it generates a dump, let's ignore it too.

17 | erl_crash.dump

18 |

19 | # Also ignore archive artifacts (built via "mix archive.build").

20 | *.ez

21 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/calc/README.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Calc

2 |

3 | Simplest project, but focused on your reader (the programmer who will maintain

4 | this code, or you in the future)

5 |

6 |

7 | ### Problem Description

8 | Build a sum calculator for your fellow programmer, using ex_docs, specs, README, and all the stuff necessary to make a non mathematician to understand your software.

9 |

10 | ### Creative Solution

11 | What is the project name ? Sum ? if sum, this is the function name. Maybe "Calculator" ? If we want to add more calculations, it's fine! But if it's only sum ? Math ! If we call calculator for only one "sum", would confuse our fellow programmer ! Calculator for a project name can be too big... let's call it calc.

12 |

13 | What about the function name ? sum or add ? They are synonymous, but what is the better option ? After some research, see the tip below:

14 |

15 | They're pretty much the same. Addition is usually used to denote summation of 2 numbers, whereas summation is used for sequences of numbers.

16 |

17 | 'Sum' is also used to denote the result of a summation/addition.

18 |

19 | Summing is the result of adding n versions of a function or equation together, which is denoted using Σ.

20 |

21 | What about the variables ? x ? var1 ? but theses are not summing knowledge to our fellow programmer! Let's call number ?

22 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/calc/config/config.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # This file is responsible for configuring your application

2 | # and its dependencies with the aid of the Mix.Config module.

3 | use Mix.Config

4 |

5 | # This configuration is loaded before any dependency and is restricted

6 | # to this project. If another project depends on this project, this

7 | # file won't be loaded nor affect the parent project. For this reason,

8 | # if you want to provide default values for your application for

9 | # 3rd-party users, it should be done in your "mix.exs" file.

10 |

11 | # You can configure your application as:

12 | #

13 | # config :calc, key: :value

14 | #

15 | # and access this configuration in your application as:

16 | #

17 | # Application.get_env(:calc, :key)

18 | #

19 | # You can also configure a 3rd-party app:

20 | #

21 | # config :logger, level: :info

22 | #

23 |

24 | # It is also possible to import configuration files, relative to this

25 | # directory. For example, you can emulate configuration per environment

26 | # by uncommenting the line below and defining dev.exs, test.exs and such.

27 | # Configuration from the imported file will override the ones defined

28 | # here (which is why it is important to import them last).

29 | #

30 | # import_config "#{Mix.env}.exs"

31 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/calc/lib/calc.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule Calc do

2 | @moduledoc """

3 | Documentation for Calc.

4 | """

5 |

6 | @typedoc "the term that will receive an addition"

7 | @type term1 :: integer | float

8 |

9 | @typedoc "the term that will be added over the first term"

10 | @type term2 :: integer | float

11 |

12 | @typedoc "result is the addition"

13 | @type result :: integer | float

14 |

15 |

16 | @typedoc "function that will in fact calculate between two terms"

17 | @type calc_operator :: fun()

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 | @doc """

23 | Add two elemets, i.e. terms, one over another.

24 |

25 | ## Examples

26 |

27 | iex> Calc.add(1, 1)

28 | 3

29 |

30 | """

31 | @spec add(term1, term2) :: result

32 | def add(term1, term2) do

33 | term1 + term2

34 | end

35 |

36 |

37 | def calculate(term1, term2, calc_operator) do

38 | %Operation{}

39 | |> Operation.set_name("jim")

40 | |> Operation.set_calc_operator(calc_operator)

41 | |> Operation.set_term1(term1)

42 | |> Operation.set_term2(term2)

43 | |> Operation.execute

44 |

45 | end

46 |

47 | end

48 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/calc/lib/operation.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule Operation do

2 | @moduledoc """

3 | Data strucutre to pipe a mathematical operation between two terms

4 | see [here](https://elixir-lang.org/getting-started/structs.html) for more details

5 | on how to deal with structs.

6 | """

7 |

8 | @typedoc "Fields of an operation data structure"

9 | @type operation :: %Operation{

10 | operation_type: String.t,

11 | term1: integer | float,

12 | term2: integer | float,

13 | result: integer | float,

14 | calc_operator: calc_operator

15 | }

16 | defstruct operation_type: nil, term1: nil, term2: nil, result: nil, calc_operator: nil

17 |

18 | @typedoc "the term that will receive an addition"

19 | @type term1 :: integer | float

20 |

21 | @typedoc "the term that will be added over the first term"

22 | @type term2 :: integer | float

23 |

24 | @typedoc "result is the addition"

25 | @type result :: integer | float

26 |

27 | @typedoc "function that will in fact make the calculation"

28 | @type calc_operator :: fun()

29 |

30 |

31 |

32 |

33 | @doc "add the operation operation_type in our data structure"

34 | @spec set_operation_type(operation, String.t) :: operation

35 | def set_operation_type(operation, operation_type), do: %{operation | operation_type: operation_type}

36 |

37 | @doc "add the first term"

38 | @spec set_term1(operation, term1) :: operation

39 | def set_term1(operation, term1), do: %{operation | term1: term1}

40 |

41 | @doc "add the term2"

42 | @spec set_term2(operation, term2) :: operation

43 | def set_term2(operation, term2), do: %{operation | term2: term2}

44 |

45 | @doc "setup the result"

46 | @spec set_result(operation, result) :: operation

47 | def set_result(operation, result) when is_integer(result),

48 | do: %{operation | result: result}

49 |

50 | @doc "setup the function that will calculate the result from both terms"

51 | @spec set_calc_operator(operation, calc_operator) :: operation

52 | def set_calc_operator(operation, calc_operator) when is_function(calc_operator),

53 | do: %{operation | calc_operator: calc_operator}

54 |

55 |

56 | @spec execute(operation) :: operation

57 | def execute(op), do: %{op | result: op.calc_operator.(op.term1, op.term2)}

58 | end

59 |

60 |

61 |

62 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/calc/mix.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule Calc.Mixfile do

2 | use Mix.Project

3 |

4 | def project do

5 | [

6 | app: :calc,

7 | version: "0.1.0",

8 | elixir: "~> 1.5",

9 | start_permanent: Mix.env == :prod,

10 | deps: deps()

11 | ]

12 | end

13 |

14 | # Run "mix help compile.app" to learn about applications.

15 | def application do

16 | [

17 | extra_applications: [:logger]

18 | ]

19 | end

20 |

21 | # Run "mix help deps" to learn about dependencies.

22 | defp deps do

23 | [{:dialyxir, "~> 0.5", only: [:dev], runtime: false}]

24 | end

25 | end

26 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/calc/test/calc_test.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule CalcTest do

2 | use ExUnit.Case

3 | doctest Calc

4 |

5 | test "calculates using add operation" do

6 | assert Calc.add(3, 3) == 6

7 | end

8 | end

9 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/calc/test/test_helper.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ExUnit.start()

2 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/.formatter.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Used by "mix format"

2 | [

3 | inputs: ["mix.exs", "{config,lib,test}/**/*.{ex,exs}"]

4 | ]

5 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/.gitignore:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # The directory Mix will write compiled artifacts to.

2 | /_build/

3 |

4 | # If you run "mix test --cover", coverage assets end up here.

5 | /cover/

6 |

7 | # The directory Mix downloads your dependencies sources to.

8 | /deps/

9 |

10 | # Where 3rd-party dependencies like ExDoc output generated docs.

11 | /doc/

12 |

13 | # Ignore .fetch files in case you like to edit your project deps locally.

14 | /.fetch

15 |

16 | # If the VM crashes, it generates a dump, let's ignore it too.

17 | erl_crash.dump

18 |

19 | # Also ignore archive artifacts (built via "mix archive.build").

20 | *.ez

21 |

22 | # Ignore package tarball (built via "mix hex.build").

23 | ninety_nine-*.tar

24 |

25 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/README.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # NinetyNine

2 |

3 | **TODO: Add description**

4 |

5 | ## Installation

6 |

7 | If [available in Hex](https://hex.pm/docs/publish), the package can be installed

8 | by adding `ninety_nine` to your list of dependencies in `mix.exs`:

9 |

10 | ```elixir

11 | def deps do

12 | [

13 | {:ninety_nine, "~> 0.1.0"}

14 | ]

15 | end

16 | ```

17 |

18 | Documentation can be generated with [ExDoc](https://github.com/elixir-lang/ex_doc)

19 | and published on [HexDocs](https://hexdocs.pm). Once published, the docs can

20 | be found at [https://hexdocs.pm/ninety_nine](https://hexdocs.pm/ninety_nine).

21 |

22 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/config/config.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # This file is responsible for configuring your application

2 | # and its dependencies with the aid of the Mix.Config module.

3 | use Mix.Config

4 |

5 | # This configuration is loaded before any dependency and is restricted

6 | # to this project. If another project depends on this project, this

7 | # file won't be loaded nor affect the parent project. For this reason,

8 | # if you want to provide default values for your application for

9 | # 3rd-party users, it should be done in your "mix.exs" file.

10 |

11 | # You can configure your application as:

12 | #

13 | # config :ninety_nine, key: :value

14 | #

15 | # and access this configuration in your application as:

16 | #

17 | # Application.get_env(:ninety_nine, :key)

18 | #

19 | # You can also configure a 3rd-party app:

20 | #

21 | # config :logger, level: :info

22 | #

23 |

24 | # It is also possible to import configuration files, relative to this

25 | # directory. For example, you can emulate configuration per environment

26 | # by uncommenting the line below and defining dev.exs, test.exs and such.

27 | # Configuration from the imported file will override the ones defined

28 | # here (which is why it is important to import them last).

29 | #

30 | # import_config "#{Mix.env}.exs"

31 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/lib/ninety_nine.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule NinetyNine do

2 | end

3 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/lib/p1.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule P1 do

2 | @moduledoc """

3 | Find the last element of a list.

4 | Example:

5 | my_last(x,[a,b,c,d]).

6 | x = d

7 | """

8 |

9 | @doc "pre-defined function"

10 | def find_last1(list), do: List.last(list)

11 |

12 | @doc "using recursion"

13 | def find_last2([]), do: []

14 | def find_last2([e]), do: e

15 | def find_last2([_|t]), do: find_last2(t)

16 |

17 | @doc "using pipe"

18 | def find_last3(list), do:

19 | list

20 | |> Enum.reverse

21 | |> List.first

22 |

23 | @doc "function composition"

24 | def find_last4(list),

25 | do: find_last_fun().(list)

26 |

27 | def find_last_fun(), do:

28 | fn list ->

29 | list |> Enum.reverse |> List.first

30 | end

31 |

32 | @doc "using index"

33 | def find_last5(list), do:

34 | list

35 | |> Enum.reverse

36 | |> Enum.at(0)

37 |

38 | @doc "using fold left"

39 | def find_last6(list), do:

40 | list

41 | |> List.foldl(0, fn(x, _) -> x end)

42 |

43 | end

44 |

45 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/lib/p2.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule P2 do

2 | @moduledoc """

3 | Find the last element of a list.

4 | Example:

5 | my_last(x,[a,b,c,d]).

6 | x = c

7 | """

8 |

9 | @doc "using recursion"

10 | def find_last_but_one([]), do: []

11 | def find_last_but_one([e, _]), do: e

12 | def find_last_but_one([_|t]), do: find_last_but_one(t)

13 |

14 |

15 | @doc "using pipes [drop the last, and get the last]"

16 | def find_last_but_one1(list), do:

17 | list

18 | |> Enum.drop(-1)

19 | |> List.last

20 |

21 |

22 | @doc "using pipes and index"

23 | def find_last_but_one2(list), do:

24 | list

25 | |> Enum.reverse

26 | |> Enum.at(1)

27 |

28 |

29 | end

30 |

31 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/lib/p3.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule P3 do

2 | @moduledoc """

3 | Find the K'th element of a list.

4 | The first element in the list is number 1.

5 | Example:

6 | ?- element_at(X,[a,b,c,d,e],3).

7 | X = c

8 | """

9 |

10 | @doc "using pre-defined function [work with negative indexes also]"

11 | def element_at(list, index), do: Enum.at(list, index)

12 |

13 | @doc "using recursion [only with positive indexes]"

14 | def element_at1([], _), do: []

15 | def element_at1([h|_], 1), do: h

16 | def element_at1([h|t], index), do:

17 | element_at1(t, index - 1)

18 |

19 |

20 | end

21 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/lib/p4.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule P4 do

2 | @moduledoc """

3 | Find the number of elements of a list.

4 | """

5 |

6 | @doc "pre-defined function"

7 | def count(list), do: Enum.count(list)

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 | @doc "using recursion"

12 | def count1([]), do: 0

13 | def count1([_|t]), do: 1 + count(t)

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 | end

18 |

19 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/lib/p5.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule P5 do

2 | @moduledoc """

3 | Reverse a list

4 | """

5 |

6 |

7 | @doc "pre-defined function"

8 | def reverse(list), do: Enum.reverse(list)

9 |

10 |

11 | @doc "using recursion"

12 | def reverse1([]), do: []

13 | def reverse1([h|t]), do: reverse(t) ++ [h]

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 | end

18 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/lib/p6.ex:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule P6 do

2 | @moduledoc """

3 | Find out whether a list is a palindrome.

4 | """

5 |

6 |

7 | def is_palindrome?(list), do: list == Enum.reverse(list)

8 |

9 |

10 | end

11 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/mix.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule NinetyNine.MixProject do

2 | use Mix.Project

3 |

4 | def project do

5 | [

6 | app: :ninety_nine,

7 | version: "0.1.0",

8 | elixir: "~> 1.6",

9 | start_permanent: Mix.env() == :prod,

10 | deps: deps()

11 | ]

12 | end

13 |

14 | # Run "mix help compile.app" to learn about applications.

15 | def application do

16 | [

17 | extra_applications: [:logger]

18 | ]

19 | end

20 |

21 | # Run "mix help deps" to learn about dependencies.

22 | defp deps do

23 | [

24 | # {:dep_from_hexpm, "~> 0.3.0"},

25 | # {:dep_from_git, git: "https://github.com/elixir-lang/my_dep.git", tag: "0.1.0"},

26 | ]

27 | end

28 | end

29 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/test/ninety_nine_test.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | defmodule NinetyNineTest do

2 | use ExUnit.Case

3 | doctest NinetyNine

4 |

5 | test "greets the world" do

6 | assert NinetyNine.hello() == :world

7 | end

8 | end

9 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/labs/ninety_nine/test/test_helper.exs:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ExUnit.start()

2 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/references/docker/DOCKER.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/henry-hz/elixir-in-a-team/92c00818ae96ff2889427b914769b521915754ad/references/docker/DOCKER.md

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/references/elixir/ARCHITECTURE.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/henry-hz/elixir-in-a-team/92c00818ae96ff2889427b914769b521915754ad/references/elixir/ARCHITECTURE.md

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/references/elixir/CLOSURES.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Closures

2 | ========

3 |

4 |

5 | What closures add is the ability to give a subroutine attributes (or rather, add attributes to a reference to a subroutine). So you can write a subroutine that takes arguments and returns a subroutine that has those arguments as parameters.

6 |

7 | ```elixir

8 | closures = (0..2)

9 | |> Enum.map &( fn () -> IO.puts(&1) end)

10 |

11 | closures

12 | |> Enum.each &(&1.())

13 | ```

14 |

15 |

16 | * https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1305570/closures-why-are-they-so-useful

17 | * https://reprog.wordpress.com/2010/02/27/closures-finally-explained/

18 | * http://www.perlmonks.org/?node=Why%20Closures%3F

19 | * https://www.electricmonk.nl/log/2011/05/20/closures-and-when-theyre-useful/ -> use case

20 | * https://www.quora.com/Why-are-closures-important-in-JavaScript

21 | * https://www.amberbit.com/blog/2015/6/14/closures-elixir-vs-ruby-vs-javascript/

22 |

23 | *

24 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/references/elixir/DEBUGGING.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Debugging

2 | =========

3 |

4 | ## Local

5 |

6 |

7 | #### IO.inspect

8 |

9 | From elixir 1.4, you can use IO.inspect even during a pipe :)

10 |

11 | ```elixir

12 | [1, 2, 3]

13 | |> IO.inspect(label: "before")

14 | |> Enum.map(&(&1 * 2))

15 | |> IO.inspect(label: "after")

16 | |> Enum.sum

17 | ```

18 |

19 | #### Pry

20 |

21 |

22 | ```elixir

23 | require IEx

24 | IEx.pry() # <- add this where you want to stop

25 | ```

26 |

27 | to restart:

28 |

29 | ```

30 | respawn

31 | ```

32 |

33 |

34 |

35 | #### Observer

36 |

37 | An insight tool for all kinds of metrics for a running BEAM node.

38 |

39 |

40 |

41 | ```

42 | :observer.start()

43 | ```

44 |

45 |

46 | * [pry-inspect](http://blog.plataformatec.com.br/2016/04/debugging-techniques-in-elixir-lang/) - debugging techniques in elixir

47 | * [observer](http://www.akitaonrails.com/2015/11/22/observing-processes-in-elixir-the-little-elixir-otp-guidebook)

48 | - observing processes in elixir - The Little Elixir & OTP Guidebook

49 | * [debuggin-phoenix](https://medium.com/@diamondgfx/debugging-phoenix-with-iex-pry-5417256e1d11) - debugging views, controllers, etc...

50 | * [tracing](https://zorbash.com/post/debugging-elixir-applications/) - tracing,

51 | EPMD, etc...

52 |

53 |

54 |

55 |

56 | ## Production

57 |

58 | #### Observer remotely

59 |

60 | ```

61 | iex --name sally -S mix s

62 | epmd -names

63 | iex --name bob

64 | Node.connect(:"sally@Gregs-MacBook-Pro-2.wework.com")

65 | :observer.start()

66 | ```

67 | *

68 | [remote-observer-scripts](https://github.com/chazsconi/connect-remote-elixir-docker)

69 | - This script allows you to start a local IEx session and connect it to a remotely running Docker node.

70 |

71 | * [recon](https://github.com/ferd/recon) - collection of functions and scripts to debug Erlang in production

72 | * [observer-cli](https://github.com/zhongwencool/observer_cli) - like the

73 | observer, but in a CLI environment

74 | *

75 | [observer-remotely](https://sgeos.github.io/elixir/erlang/observer/2016/09/16/elixir_erlang_running_otp_observer_remotely.html)

76 | - use the graphical observer connected to a remote node

77 |

78 |

79 | * [beam-without-epmd](https://www.erlang-solutions.com/blog/erlang-and-elixir-distribution-without-epmd.html)

80 | - Erlang (and Elixir) distribution without epmd

81 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/references/elixir/DOCUMENTATION.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Documentation

2 | =============

3 |

4 | An important part of writing code is making it easy to understand for other developers or your future self.

5 |

6 | In a perfect world, this is achieved through clear and concise code that shows the intent of the developer. There really is no better documentation than the code itself.

7 |

8 | However, comments and documentation are a critically important tool for learning. Newbies can’t be expected to pick up something new from the source code alone, and even experienced developers will spend a lot of their time referencing documentation in order to achieve their goals.

9 |

10 | Documentation in Elixir is a first-class citizen, and so there are a couple of tools that make writing and using documentation in Elixir particularly useful.

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 | *

15 | [writing-documentation](https://www.culttt.com/2016/10/19/writing-comments-documentation-elixir/)

16 | - details and examples on how to write documentations for modules, functions,

17 | etc..

18 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/references/elixir/ELIXIR.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Elixir Quick Reference

2 | A quick reference for the Elixir programming Language and standard library.

3 |

4 | Elixir Website: http://elixir-lang.org/

5 | Elixir Documentation: http://elixir-lang.org/docs.html

6 | Elixir Source: https://github.com/elixir-lang/elixir

7 | Try Elixir Online: https://glot.io/new/elixir

8 | Elixir Regex editor/testor: http://www.elixre.uk/

9 | This Document: https://github.com/itsgreggreg/elixir_quick_reference

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 | # Table of Contents

14 |

15 | - [Basic Types](#basic-types)

16 | - [Integer](#integer)

17 | - [Float](#float)

18 | - [Atom](#atom)

19 | - [Boolean](#boolean)

20 | - [Nil](#nil)

21 | - [Binary](#binary)

22 | - [String](#string)

23 | - [Escape Sequences](#escape-sequences)

24 | - [Regular Expression](#regular-expression)

25 | - [Collection Types](#collection-types)

26 | - [List](#list)

27 | - [Charlist](#charlist)

28 | - [Tuple](#tuple)

29 | - [Keyword List](#keyword-list)

30 | - [Map](#map)

31 | - [Struct](#struct)

32 | - [Range](#range)

33 | - [Streams](#streams)

34 | - [Syntax](#syntax)

35 | - [Variables](#variables)

36 | - [Operators](#operators)

37 | - [Standard infix](#standard-infix)

38 | - [Standard prefix](#standard-prefix)

39 | - [= (match)](#-match)

40 | - [^ (pin)](#-pin)

41 | - [|> (pipe)](#-pipe)

42 | - [=~ (string match)](#-string-match)

43 | - [? (codepoint)](#-codepoint)

44 | - [& (capture)](#-capture)

45 | - [Ternary](#ternary)

46 | - [in](#in)

47 | - [Comments](#comments)

48 | - [Semicolons](#semicolons)

49 | - [Do, End](#do-end)

50 | - [Pattern Matching](#pattern-matching)

51 | - [Binaries](#binaries)

52 | - [Reserved Words](#reserved-words)

53 | - [Truthiness](#truthiness)

54 | - [Sorting](#sorting)

55 | - [Modules](#modules)

56 | - [Declaration](#declaration)

57 | - [Module Functions](#module-functions)

58 | - [Private Functions](#private-functions)

59 | - [Working with other modules](#working-with-other-modules)

60 | - [Attributes](#attributes)

61 | - [Documentation](#documentation)

62 | - [Introspection](#introspection)

63 | - [Errors](#errors)

64 | - [Raise](#raise)

65 | - [Custom Error](#custom-error)

66 | - [Rescue](#rescue)

67 | - [Control Flow](#control-flow)

68 | - [if/unless](#ifunless)

69 | - [case](#case)

70 | - [cond](#cond)

71 | - [throw/catch](#throwcatch)

72 | - [with](#with)

73 | - [Guards](#guards)

74 | - [Anonymous Functions](#anonymous-functions)

75 | - [Comprehensions](#comprehensions)

76 | - [Sigils](#sigils)

77 | - [Metaprogramming](#metaprogramming)

78 | - [Processes](#processes)

79 | - [Structs](#structs)

80 | - [Working with Files](#working-with-files)

81 | - [Erlang Interoperability](#erlang-interoperability)

82 | - [IEx](#iex)

83 | - [Mix](#mix)

84 | - [Applications](#applications)

85 | - [Tasks](#tasks)

86 | - [Tests](#tests)

87 | - [Style Guide](#style-guide)

88 |

89 |

90 |

91 |

92 | ## Basic Types

93 |

94 | ### Integer

95 | Can be specified in base 10, hex, or binary. All are stored as base 10.

96 |

97 | ```elixir

98 | > 1234567 == 1_234_567 # true

99 | > 0xcafe == 0xCAFE # true

100 | > 0b10101 == 65793 # true

101 | > 0xCafe == 0b1100101011111110 # true

102 | > 0xCafe == 51_966 # true

103 | > Integer.to_string(51_966, 16) == "CAFE" # true

104 | > Integer.to_string(0xcafe) == "51996" # true

105 | ```

106 |

107 | ### Float

108 | 64bit double precision. Can be specified with an exponent. Cannot begin or end with `.`.

109 |

110 | ```elixir

111 | > 1.2345

112 | > 0.001 == 1.0e-3 # true

113 | > .001 # syntax error!

114 | ```

115 |

116 | ### Atom

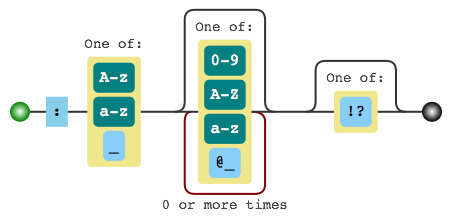

117 | Constants whose name is their value.

118 | Are named in this format:

119 |

120 |

121 | To use other characters you must quote the atom.

122 | TODO: Note which characters can be used when quoted.

123 | Stored in a global table once used and never de-allocated so avoid programmatic creation.

124 |

125 | ```elixir

126 | > :something

127 | > :_some_thing

128 | > :allowed?

129 | > :Some@Thing@12345

130 | > :"Üñîçødé and Spaces"

131 | > Atom.to_string(:Yay!) # "Yay!"

132 | > :123 # syntax error!

133 | ```

134 |

135 | ### Boolean

136 | `true` and `false` are just syntactic sugar for `:true` and `:false` and not a special type.

137 |

138 | ```elixir

139 | > true == :true # true

140 | > false == :false # true

141 | > is_boolean(:true) # true

142 | > is_atom(false) # true

143 | > is_boolean(:True) # false!

144 | ```

145 |

146 | ### Nil

147 | `nil` is syntactic sugar for `:nil` and is not a special type.

148 |

149 | ```elixir

150 | > nil == :nil # true

151 | > is_atom(nil) # true

152 | ```

153 |

154 | ### Binary

155 | A binary is a sequence of bytes enclosed in `<< >>` and separated with `,`.

156 | By default each number is 8 bits though size can be specified with:

157 | `::size(n)`, `::n`, `::utf8`, `::utf16`, `::utf32` or `::float`

158 | If the number of bits in a binary is not divisible by 8, it is considered a bitstring.

159 | Binaries are concatenated with `<>`.

160 | ```elixir

161 | > <<0,1,2,3>>

162 | > <<100>> == <<100::size(8)>> # true

163 | > <<4::float>> == <<64, 16, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0>> # true

164 | > <<65::utf32>> == <<0, 0, 0, 65>> # true

165 | > <<0::2, 1::2>> == <<1::4>> # true

166 | > <<1,2>> <> <<3,4>> == <<1,2,3,4>> # true

167 | > is_binary(<<1,2,3,4>>) # true

168 | > is_binary(<<1::size(4)>>) # false!, num of bits not devisible by 8

169 | > is_bitstring(<<1::size(4)>>) # true

170 | ```

171 |

172 | ### String

173 | Strings are UTF-8 encoded binaries. They are enclosed in double quotes(`"`).

174 | They can span multiple lines and contain interpolations.

175 | Interpolations are enclosed in `#{}` and can contain any expression.

176 | Strings, being binaries, are concatenated with `<>`.

177 |

178 | ```elixir

179 | > "This is a string."

180 | > "☀★☂☻♞☯☭☢€→☎♫♎⇧☮♻⌘⌛☘☊♔♕♖☦♠♣♥♦♂♀" # no problem :)

181 | > "This is an #{ Atom.to_string(:interpolated) } string."

182 | > "Where is " <> "my other half?"

183 | > "multi\nline" == "multi

184 | line" # true

185 | > <<69,108,105,120,105,114>> == "Elixir" # true

186 | > String.length("🎩") # 1

187 | > byte_size("🎩") # 4

188 | > is_binary("any string") # true

189 | > String.valid?("こんにちは") # true

190 | > String.valid?("hello" <> <<255>>) # false!

191 | > String.valid?(<<4>>) # true

192 | > String.printable?(<<4>>) # false! 4 is a valid UTF-8 codepoint, but is not printable.

193 | ```

194 | #### Escape Sequences

195 | characters | whitespace | control sequences

196 | --------------------------|---------------------|----------------------

197 | `\"` – double quote | `\b` – backspace | `\a` – bell/alert

198 | `\'` – single quote | `\f` - form feed | `\d` - delete

199 | `\\` – single backslash | `\n` – newline | `\e` - escape

200 | | `\s` – space | `\r` – carriage return

201 | | `\t` - tab | `\0` - null byte

202 | | `\v` – vertical tab |

203 |

204 | `\x...` - character with hexadecimal representation.

205 | `\x{...}` - character with hexadecimal representation with one or more hexadecimal digits.

206 | ```elixir

207 | > "\x3f" == "?" # true

208 | > "\x{266B}" == "♫" # true

209 | > "\x{2660}" == "♠" # true

210 | ```

211 |

212 |

213 |

214 | ### Regular Expression

215 | Inherited from Erlang's `re` module and are Perl compatible.

216 | Written literally with the `~r` [Sigil](#sigils) and can span multiple lines.

217 | Can have a number of modifiers specified directly after the pattern.

218 | Many functions take a captures option that limits captures.

219 |

220 | **Modifiers**:

221 | - `u` enables unicode specific patterns like \p and changes escapes like \w, \W, \s and friends to also match on unicode. It expects valid unicode strings to be given on match

222 | - `i` ignore case

223 | - `s` dot matches newlines and also set newline to anycrlf.

224 | - `m` ^ and $ match the start and end of each line; use \A and \z to match the end or start of the string

225 | - `x` whitespace characters are ignored except when escaped and `#` delimits comments

226 | - `f` forces the unanchored pattern to match before or at the first newline, though the matched text may continue over the newline

227 | r - inverts the “greediness” of the regexp

228 |

229 | **To override newline treatment start the pattern with**:

230 | - `(*CR)` carriage return

231 | - `(*LF)` line feed

232 | - `(*CRLF)` carriage return, followed by linefeed

233 | - `(*ANYCRLF)` any of the three above

234 | - `(*ANY)` all Unicode newline sequences

235 |

236 | ```elixir

237 | > Regex.compile!("caf[eé]") == ~r/caf[eé]/ # true

238 | > Regex.match?(~r/caf[eé]/, "café") # true

239 | > Regex.regex?(~r"caf[eé]") # true

240 | > Regex.regex?("caf[eé]") # false! string not compiled regex

241 | > Regex.run(~r/hat: (.*)/, "hat: 🎩", [capture: :all_but_first]) == ["🎩"] # true

242 | # Modifiers

243 | > Regex.match?(~r/mr. bojangles/i, "Mr. Bojangles") # true

244 | > Regex.compile!("mr. bojangles", "sxi") # ~r/mr. bojangles/sxi

245 | # Newline overrides

246 | > ~r/(*ANY)some\npattern/

247 | ```

248 |

249 | ## Collection Types

250 |

251 | ### List

252 | Simple linked lists that can be of any size and can have elements of any type.

253 | They are enclosed in `[ ]` and elements are comma separated.

254 | Concatenated with `++` and subtracted with `--`.

255 | Can be constructed with the cons operator `|`.

256 | Best for sequential access, fastest when elements are added and subtracted from the head.

257 | Instead of building a list by adding to its tail, add to the head and reverse the list.

258 | List implements the enumerable protocol so we use Enum for many common operations.

259 |

260 | ```elixir

261 | > [1, 2, 3.4, "a", "b", :c, [:d]]

262 | > [ 1 | [2 | [3]]] == [1, 2, 3] # true

263 | > [1, 2, 3.4] ++ ["a", "b", :c] # [1, 2, 3.4, "a", "b", :c]

264 | > [1, 2, 3.4, "a", "b", :c, [:d]] -- [2, "a", "c"] # [1, 3.4, "b", :c, [:d]]

265 | > hd [1, 2, 3] # 1

266 | > tl [1, 2, 3] # [2, 3]

267 | > length [:a, :b, :c, :d] # 4

268 | > Enum.reverse [:a, :b, :c] # [:c, :b, :a]

269 | > Enum.member? [:a, :b], :b # true

270 | > Enum.join [:a, :b], "_" # "a_b"

271 | > Enum.at [:a, :b, :c], 1 # :b

272 | ```

273 |

274 | ### Charlist

275 | A [List](#list) of UTF-8 codepoints.

276 | Other than syntax they are exactly the same as Lists and are not a unique class.

277 | Can span multiple lines and are delimited with single quotes `'`.

278 | Have the same [Escape Sequences](#escape-sequences) as String.

279 |

280 | ```elixir

281 | > 'char list'

282 | > [108, 105, 115, 116] == 'list' # true

283 | > 'turbo' ++ 'pogo' # 'turbopogo'

284 | > 'char list' -- 'a l' # 'christ'

285 | > hd 'such list' == ?s # true

286 | > String.to_char_list "tacosalad" # 'tacosalad'

287 | > List.to_string 'frijoles' # "frijoles"

288 | > [?Y, ?e, ?a, ?h] == 'Yeah' # true

289 | ```

290 |

291 | ### Tuple

292 | Can be of any size and have elements of any type.

293 | Elements are stored contiguously in memory.

294 | Enclosed in `{ }` and elements are comma separated.

295 | Fast for index-based access, slow for a large number of elements.

296 |

297 | ```elixir

298 | > { :a, 1, {:b}, [2]}

299 | > put_elem({:a}, 0, :b) # {:b}

300 | > elem({:a, :b, :c}, 1) # b

301 | > Tuple.delete_at({:a, :b, :c}, 1) # {:a, :c}

302 | > Tuple.insert_at({:a, :c}, 1, :b) # {:a, :b, :c}

303 | > Tuple.to_list({:a, :b, :c}) # [:a, :b, :c]

304 | ```

305 |

306 | ### Keyword List

307 | A List of 2 element Tuples where each Tuple's first element is an Atom.

308 | This atom is refered to as the keyword, or key.

309 | Have a special concice syntax that omits the Tuple's brackets and places the key's colon on the right.

310 | Being Lists they:

311 | - are order as specified

312 | - can have duplicate elements and multiple elements with the same key

313 | - are fastest when accessed at the head.

314 | - are concatenated with `++` and subtracted with `--`.

315 |

316 | Elements can be accessed with `[:key]` notation. The first Element with a matching `:key` will be returned.

317 | 2 Keyword Lists are only equal if all elements are equal and in the same order.

318 |

319 | ```elixir

320 | # Full Syntax

321 | > [{:a, "one"}, {:b, 2}]

322 | # Concice Syntax

323 | > [a: "one", b: 2]

324 | > [a: 1] ++ [a: 2, b: 3] == [a: 1, a: 2, b: 3] # true

325 | > [a: 1, b: 2] == [b: 2, a: 1] # false! elements are in different order

326 | > [a: 1, a: 2][:a] == 1 # true

327 | > Keyword.keys([a: 1, b: 2]) # [:a, :b]

328 | > Keyword.get_values([a: 1, a: 2], :a) # [1, 2]

329 | > Keyword.keyword?([{:a,1}, {:b,2}]) # true

330 | > Keyword.keyword?([{:a,1}, {"b",2}]) # false! "b" is not an Atom

331 | > Keyword.delete([a: 1, b: 2], :a) # [b: 2]

332 | ```

333 |

334 | ### Map

335 | Key - Value store where Keys and Values are of any type.

336 | Cannot have multiple values for the same key and are unordered.

337 | `Map`s are enclosed in `%{ }`, elements are comma seperated, and elemets have the form: key `=>` value.

338 | If all keys are `Atom`s, the `=>` can be omitted and the `Atom`'s `:` must be on the right.

339 | Values are accessed with `[key]` notation.

340 | Maps can be accessed with `.key` notation if key is an `Atom`.

341 | Maps can be updated by enclosing them in `%{}` and using the cons `|` operator.

342 | Maps can be of any size and are fastest for key based lookup.

343 |

344 | ```elixir

345 | > %{:a => 1, 1 => ["list"], [2,3,4] => {"a", "b"}}

346 | > %{:a => 1, :b => 2} == %{a: 1, b: 2} # true

347 | > %{a: "one", b: "two", a: 1} == %{a: 1, b: "two"} # true

348 | > %{a: "one", b: "two"} == %{b: "two", a: "one"} # true

349 | > %{a: "one", b: "two"}[:b] # "two"

350 | > %{a: "one", b: "two"}.b # "two"

351 | > %{a: "one", a: 1} == %{a: 1} # true

352 | > %{:a => "one", "a" => "two"}."a" == "two" # false! watchout

353 | > Map.keys( %{a: 1, b: 2} ) == [:a, :b] # true

354 | > %{ %{a: 1, b: 2, c: 3} | :a => 4, b: 5 } # %{a: 4, b: 5, c: 3}

355 | > Map.merge( %{a: 1, b: 2}, %{a: 4, c: 3} ) # %{a: 4, b: 2, c: 3}

356 | > Map.put( %{a: 1}, :b, 2 ) == %{a: 1, b: 2} # true

357 | > Kernel.get_in # TODO

358 | > Kernel.put_in # TODO

359 | ```

360 |

361 | ### Struct

362 | Structs can be thought of as bare Maps with pre-defined keys, default values and where the keys must be atoms.

363 | Structs are defined at the top level of a Module and take the Module's name.

364 | Structs do not implement the Access or Enumerable protocol and can be considered bare Maps.

365 | Structs have a special field called `__struct__` that holds the name of the struct.

366 |

367 | ```elixir

368 | defmodule City do

369 | defstruct name: "New Orleans", founded: 1718

370 | end

371 | nola = %City{}

372 | chi = %City{name: "Chicago", founded: 1833}

373 | nola.name # "New Orleans"

374 | chi.founded # 1833

375 | nola.__struct__ # City

376 | ```

377 |

378 | ### Range

379 | Used to specify the first and last elements of something.

380 | Just a Struct of type Range with a `first` field and a `last` field.

381 | Have a special `..` creation syntax but can also be created like any other struct.

382 |

383 | ```elixir

384 | > a = 5..10

385 | > b = Range.new(5, 10)

386 | > c = %Range{first: 5, last: 10}

387 | > Range.range?(c) # true

388 | > Enum.each(5..10, fn(n) -> n*n end) # prints all the squares of 5..10

389 | > Map.keys(5..10) # [:__struct__, :first, :last]

390 | > (5..10).first # 5

391 | ```

392 |

393 | ### Streams

394 | Lazy enumerables.

395 | Are created out of enumerables with functions in the `Stream` module.

396 | Elements are not computed until a method from the `Enum` module is called on them.

397 | ```elixir

398 | > a = Stream.cycle 'abc'

399 | #Function<47.29647706/2 in Stream.unfold/2> # Infinate Stream created

400 | > Enum.take a, 10 # Enum.take computes the 10 elements

401 | 'abcabcabca'

402 | ```

403 |

404 | With [Stream.unfold/2](http://elixir-lang.org/docs/stable/elixir/Stream.html#unfold/2) you can create an arbitrary stream.

405 | ```elixir

406 | > s = Stream.unfold( 5,

407 | fn 0 -> nil # returning nil halts the stream

408 | n -> {n, n-1} # return format {next-val, rest}

409 | end)

410 | > Enum.to_list(s)

411 | [5, 4, 3, 2, 1]

412 | ```

413 |

414 | ## Syntax

415 |

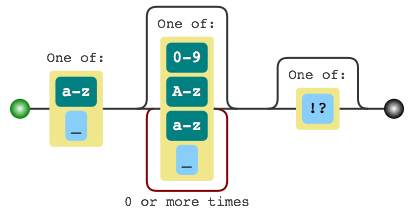

416 | ### Variables

417 | Are declared and initialized upon use.

418 | Are named in the following format:

419 |

420 |

421 | Can hold any data structure and can be assigned more than once.

422 |

423 | ```elixir

424 | > something = :anything

425 | > something = ["a", "list", "of", "strings"]

426 | > _yeeHaw1234! = %{:a => :b}

427 | ```

428 |

429 | ### Operators

430 | #### Standard infix

431 | - Equality `==`, `!=`

432 | - Strict equality `===` and `!==` do not coerce Floats to Integers. `1 === 1.0 #false`

433 | - Comparison `>`, `<`, `>=`, `<=`

434 | - Logic, short-circuiting `&&` and `||`

435 | - Boolean only Logic, short-circuiting `and` and `or`. (Only left side must be boolean)

436 | - Math `+`, `-`, `*`, `/`

437 |

438 | #### Standard prefix

439 | - Negation, any type `!`, `!1 == false`

440 | - Negation, boolean only `not`, `not is_atom(5) == true`

441 |

442 | #### = (match)

443 | left `=` right

444 | Performs a [Pattern Match](#pattern-matching).

445 |

446 | #### ^ (pin)

447 | Used to pin the value of a variable in the left side of a [Pattern Match](#pattern-matching).

448 | ```elixir

449 | a = "thirty hams"

450 | {b, ^a} = {:i_need, "thirty hams"} # `b` is set to `:i_need`

451 | {^a, {^a}} = {"thirty hams", {"thirty hams"}} # nothing is set, but the match succedes

452 | ```

453 |

454 | #### |> (pipe)

455 | `|>`

456 | Takes the result of a statement on its left and passes as the first argument to the function on its right.

457 | The statement on the left can be on the preceeding line of code.

458 | ```elixir

459 | > [1,2,3] |> hd |> Integer.to_string |> IO.inspect # "1"

460 | # ⇣ doesn't work in iex

461 | hd([1,2,3])

462 | |> Integer.to_string

463 | |> IO.inspect # "1"

464 | ```

465 |

466 | #### =~ (string match)

467 | `=~`

468 | Takes a string on the left and on the right either a string or a regular expression.

469 | If the string on the right is a substring of left, `true` is returned.

470 | If the regular expression on the right matches the string on the left, `true` is returned.

471 | Otherwise `false` is returned.

472 | ```elixir

473 | > "abcd" =~ ~r/c(d)/ # true

474 | > "abcd" =~ ~r/e/ # false

475 | > "abcd" =~ "bc" # true

476 | > "abcd" =~ "ad" # false

477 | ```

478 |

479 | #### ? (codepoint)

480 | `?`

481 | Returns the UTF-8 codepoint of the character immediately to its right.

482 | Can only take one character, accepts [Escape Sequences](#escape-sequences).

483 | **Remember** [Charlists](#charlist) are just lists of UTF-8 codepoints.

484 | ```elixir

485 | > ?a # 97

486 | > ?♫ # 9835

487 | > ?\s # 32

488 | > ?? # 63

489 | > [?♀, ?!] == '♀!' # true

490 | ```

491 |

492 | #### & (capture)

493 | - TODO

494 |

495 | #### Ternary

496 | Elixir has no ternary operator. The same effect though can be achieved with the `if` macro.

497 | ```elixir

498 | > a = if true, do: "True!", else: "False!"

499 | > a == "True!" # true

500 | ```

501 |

502 | #### in

503 | left `in` right.

504 | Used to check if the **enumerable** on the right contains the data structure on the left.

505 | Right hand side must implement the Enumerable Protocol.

506 |

507 | ```elixir

508 | > :b in [:a, :b, :c] # true

509 | > [:c] in [1,3,[:c]] # true

510 | > :ok in {:ok} # ERROR: protocol Enumerable not implemented for {:ok}

511 | ```

512 |

513 | ### Comments

514 | `#` indicates that itself and anything after it until a new line is a comment. That is all.

515 |

516 | ### Semicolons

517 | Semicolons can be used to terminate statements but in practice are rarely if ever used.

518 | The only required usage is to put more than one statement on the same line. `a = 1; b = 2`

519 | This is considered bad style and placing them on seperate lines is much prefered.

520 |

521 | ### Do, End

522 | Blocks of code passed to macros start with `do` and end with `end`.

523 | ```elixir

524 | if true do

525 | "True!"

526 | end

527 |

528 | if true do "True!" end

529 |

530 | # inside a module

531 | def somefunc() do

532 | IO.puts "multi line"

533 | end

534 |

535 | if true do

536 | "True!"

537 | else

538 | "False!"

539 | end

540 | ```

541 |

542 | You can pass the block as a single line and without `end` with some extra puctuation.

543 | ```elixir

544 | # ⇣ ⇣ ⇣ no end keyword

545 | if true, do: "True!"

546 | # ⇣ ⇣ ⇣ ⇣ ⇣ no end keyword

547 | if true, do: "True", else: "False!"

548 | # inside a module

549 | # ⇣ ⇣ ⇣ no end keyword

550 | def someFunc(), do: IO.puts "look ma, one line!"

551 | ```

552 |

553 | Syntactic sugar for

554 | ```elixir

555 | if(true, [{:do, "True!"}, {:else, "False!"}])

556 | def(someFunc(), [{:do, IO.puts "look ma, one line!"}])

557 | ```

558 |

559 | ### Pattern Matching

560 | A match has 2 main parts, a **left** side and a **right** side.

561 | ```elixir

562 | # ┌Left ┌Right

563 | # ┌───┴───┐ ┌───┴──────┐

564 | {:one, x} = {:one, :two}

565 | # ┌Right

566 | # ┌───┴──────┐

567 | case {:one, :two} do

568 | # ┌Left

569 | # ┌───┴───┐

570 | {:one, x} -> IO.puts x

571 | # ┌Left

572 | _ -> IO.puts "no other match"

573 | end

574 | ```

575 |

576 | The **right** side is a **data structure** of any kind.

577 | The **left** side attempts to **match** itself to the **data structure** on the right and **bind** any **variables** to **substructures**.

578 |

579 | The simplest **match** has a lone **variable** on the **left** and will **match** anything:

580 | ```elixir

581 | # in these examples `x` will be set to whatever is on the right

582 | x = 1

583 | x = [1,2,3,4]

584 | x = {:any, "structure", %{:whatso => :ever}}

585 | ```

586 |

587 | But you can place the **variables** inside a **structure** so you can **capture** a **substructure**:

588 | ```elixir

589 | # `x` gets set to only the `substructure` it matches

590 | {:one, x} = {:one, :two} # `x` is set to `:two`

591 | [1,2,n,4] = [1,2,3,4] # `n` is set to `3`

592 | [:one, p] = [:one, {:apple, :orange}] # `p` is set to `{:apple, :orange}`

593 | ```

594 |

595 | There is also a special `_` **variable** that works exactly like other **variables** but tells elixir, "Make sure something is here, but I don't care exactly what it is.":

596 | ```elixir

597 | # in all of these examples, `x` gets set to `:two`

598 | {_, x} = {:one, :two}

599 | {_, x} = {:three, :two}

600 | [_,_,x,_] = [1,{2},:two,3]

601 | ```

602 |

603 | If you place a **variable** on the **right**, its **value** is used:

604 | ```elixir

605 | # ┌Same as writing {"twenty hams"}

606 | a = {"twenty hams"} ⇣

607 | {:i_have, {b}} = {:i_have, a} # `b` is set to "twenty hams"

608 | ```

609 |

610 | In the previous example you are telling elixir: I want to **match** a **structure** that is a **tuple**, and this **tuple's** first element is going to be the atom **:i_have**. This **tuple's** second element is going to be a **tuple**. This **second tuple** is going to have one element and whatever it is I want you to bind it to the variable **b**.

611 |

612 | If you want to use the **value** of a **variable** in your structure on the **left** you use the `^` operator:

613 | ```elixir

614 | a = "thirty hams"

615 | {b, ^a} = {:i_need, "thirty hams"} # `b` is set to `:i_need`

616 | {^a, {^a}} = {"thirty hams", {"thirty hams"}} # nothing is set, but the match succedes

617 | ```

618 |

619 | #### Maps

620 | Individual keys can be matched in Maps like so:

621 | ```elixir

622 | nola = %{ name: "New Orleans", founded: 1718 }

623 | %{name: city_name} = nola # city_name now equals "New Orleans"

624 | %{name: _, founded: city_founded} = nola # Map must have both a name and a founded key

625 | ```