64 | {% for post in site.posts %}

65 | {% include post-list-item.html %}

66 | {% endfor %}

67 |

68 |

69 | {% endif %}

70 |

71 |

72 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/_sass/_base.scss:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | body {

2 | background: $brand-color;

3 | color: $text-color;

4 | font-family: $font-family;

5 | font-size: 1.3125em;

6 | line-height: 1.5;

7 | }

8 |

9 | h1 {

10 | font-size: 3em;

11 | margin: .5em auto;

12 | }

13 |

14 | h2 {

15 | font-size: 2em;

16 | margin: 1em auto;

17 | text-align: center;

18 | }

19 |

20 | h3 {

21 | font-size: 1.5em;

22 | margin: 1.3333em auto;

23 | text-align: center;

24 | }

25 |

26 | h4 {

27 | font-size: 1.25em;

28 | font-style: italic;

29 | margin: 1.875em auto;

30 | text-align: center;

31 | }

32 |

33 | h5 {

34 | font-size: 1em;

35 | font-style: italic;

36 | margin: 2em auto;

37 | text-align: center;

38 | }

39 |

40 | h6 {

41 | font-size: .875em;

42 | font-style: italic;

43 | margin: 2.25em auto;

44 | text-align: center;

45 | }

46 |

47 | em {

48 | font-style: italic;

49 | }

50 |

51 | strong {

52 | font-weight: bold;

53 | }

54 |

55 | a {

56 | color: $text-color;

57 | }

58 |

59 | a:focus {

60 | outline: 1px dashed $text-color;

61 | }

62 |

63 | blockquote {

64 | margin: 2em auto;

65 | opacity: .8;

66 | > * {

67 | padding: 0 3em;

68 | }

69 | }

70 |

71 | blockquote.epigraph {

72 | font-style: italic;

73 | }

74 |

75 | small {

76 | font-size: .75em;

77 | }

78 |

79 | p > cite {

80 | display: block;

81 | text-align: right;

82 | }

83 |

84 | hr {

85 | border: 0;

86 | height: 0;

87 | @include divider;

88 | margin: 4em 0;

89 | }

90 |

91 | img {

92 | display: flex;

93 | max-width: 100%;

94 | height: auto;

95 | margin: 2em auto;

96 | }

97 |

98 | figure img {

99 | margin: 2em auto 1em;

100 | }

101 |

102 | figcaption {

103 | font-size: .875em;

104 | font-style: italic;

105 | text-align: center;

106 | margin-bottom: 2em;

107 | opacity: .7;

108 | }

109 |

110 | .divided::after {

111 | content: "";

112 | @include divider;

113 | }

114 |

115 | .home {

116 | max-width: 24em;

117 | margin: auto;

118 | padding: 4em 1em;

119 | }

120 |

121 | .content-title {

122 | font-size: 2em;

123 | margin-bottom: 2em;

124 | text-align: center;

125 | }

126 |

127 | .post-date {

128 | color: $muted-text-color;

129 | display: block;

130 | font-size: .825em;

131 | white-space: nowrap;

132 | text-transform: uppercase;

133 | .post-link & {

134 | padding: .5em 0;

135 | }

136 | }

137 |

138 | .site-credits {

139 | margin: 0 auto 2em;

140 | padding: 0 2em;

141 | text-align: center;

142 | }

143 |

144 | .skip-navigation {

145 | background: $brand-color;

146 | border: 1px dashed transparent;

147 | display: block;

148 | font-size: .875em;

149 | font-weight: 700;

150 | margin-top: -2.625rem;

151 | padding: .5rem;

152 | text-align: center;

153 | text-decoration: none;

154 | text-transform: uppercase;

155 | &:hover,

156 | &:focus {

157 | background: lighten($brand-color, 2.5%);

158 | border-color: $text-color;

159 | margin-top: 0;

160 | }

161 | }

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Contributor Covenant Code of Conduct

2 |

3 | ## Our Pledge

4 |

5 | In the interest of fostering an open and welcoming environment, we as

6 | contributors and maintainers pledge to making participation in our project and

7 | our community a harassment-free experience for everyone, regardless of age, body

8 | size, disability, ethnicity, sex characteristics, gender identity and expression,

9 | level of experience, education, socio-economic status, nationality, personal

10 | appearance, race, religion, or sexual identity and orientation.

11 |

12 | ## Our Standards

13 |

14 | Examples of behavior that contributes to creating a positive environment

15 | include:

16 |

17 | * Using welcoming and inclusive language

18 | * Being respectful of differing viewpoints and experiences

19 | * Gracefully accepting constructive criticism

20 | * Focusing on what is best for the community

21 | * Showing empathy towards other community members

22 |

23 | Examples of unacceptable behavior by participants include:

24 |

25 | * The use of sexualized language or imagery and unwelcome sexual attention or

26 | advances

27 | * Trolling, insulting/derogatory comments, and personal or political attacks

28 | * Public or private harassment

29 | * Publishing others' private information, such as a physical or electronic

30 | address, without explicit permission

31 | * Other conduct which could reasonably be considered inappropriate in a

32 | professional setting

33 |

34 | ## Our Responsibilities

35 |

36 | Project maintainers are responsible for clarifying the standards of acceptable

37 | behavior and are expected to take appropriate and fair corrective action in

38 | response to any instances of unacceptable behavior.

39 |

40 | Project maintainers have the right and responsibility to remove, edit, or

41 | reject comments, commits, code, wiki edits, issues, and other contributions

42 | that are not aligned to this Code of Conduct, or to ban temporarily or

43 | permanently any contributor for other behaviors that they deem inappropriate,

44 | threatening, offensive, or harmful.

45 |

46 | ## Scope

47 |

48 | This Code of Conduct applies both within project spaces and in public spaces

49 | when an individual is representing the project or its community. Examples of

50 | representing a project or community include using an official project e-mail

51 | address, posting via an official social media account, or acting as an appointed

52 | representative at an online or offline event. Representation of a project may be

53 | further defined and clarified by project maintainers.

54 |

55 | ## Enforcement

56 |

57 | Instances of abusive, harassing, or otherwise unacceptable behavior may be

58 | reported by contacting the project team at hello@patdryburgh.com. All

59 | complaints will be reviewed and investigated and will result in a response that

60 | is deemed necessary and appropriate to the circumstances. The project team is

61 | obligated to maintain confidentiality with regard to the reporter of an incident.

62 | Further details of specific enforcement policies may be posted separately.

63 |

64 | Project maintainers who do not follow or enforce the Code of Conduct in good

65 | faith may face temporary or permanent repercussions as determined by other

66 | members of the project's leadership.

67 |

68 | ## Attribution

69 |

70 | This Code of Conduct is adapted from the [Contributor Covenant][homepage], version 1.4,

71 | available at https://www.contributor-covenant.org/version/1/4/code-of-conduct.html

72 |

73 | [homepage]: https://www.contributor-covenant.org

74 |

75 | For answers to common questions about this code of conduct, see

76 | https://www.contributor-covenant.org/faq

77 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/_sass/_syntax-highlighting.scss:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | /**

2 | * Syntax highlighting styles

3 | */

4 |

5 | code.highlighter-rouge {

6 | background: $highlight;

7 | font-family: courier, monospace;

8 | font-size: .875em;

9 | }

10 |

11 | .highlight {

12 | background: #fff;

13 | font-family: courier, monospace;

14 | font-size: .875em;

15 | margin: 2rem auto;

16 |

17 | > * {

18 | padding: 0 1.5rem;

19 | }

20 |

21 | .highlighter-rouge & {

22 | background: $highlight;

23 | }

24 |

25 | .c { color: #998; font-style: italic } // Comment

26 | .err { color: #a61717; background-color: #e3d2d2 } // Error

27 | .k { font-weight: bold } // Keyword

28 | .o { font-weight: bold } // Operator

29 | .cm { color: #998; font-style: italic } // Comment.Multiline

30 | .cp { color: #999; font-weight: bold } // Comment.Preproc

31 | .c1 { color: #998; font-style: italic } // Comment.Single

32 | .cs { color: #999; font-weight: bold; font-style: italic } // Comment.Special

33 | .gd { color: #000; background-color: #fdd } // Generic.Deleted

34 | .gd .x { color: #000; background-color: #faa } // Generic.Deleted.Specific

35 | .ge { font-style: italic } // Generic.Emph

36 | .gr { color: #a00 } // Generic.Error

37 | .gh { color: #999 } // Generic.Heading

38 | .gi { color: #000; background-color: #dfd } // Generic.Inserted

39 | .gi .x { color: #000; background-color: #afa } // Generic.Inserted.Specific

40 | .go { color: #888 } // Generic.Output

41 | .gp { color: #555 } // Generic.Prompt

42 | .gs { font-weight: bold } // Generic.Strong

43 | .gu { color: #aaa } // Generic.Subheading

44 | .gt { color: #a00 } // Generic.Traceback

45 | .kc { font-weight: bold } // Keyword.Constant

46 | .kd { font-weight: bold } // Keyword.Declaration

47 | .kp { font-weight: bold } // Keyword.Pseudo

48 | .kr { font-weight: bold } // Keyword.Reserved

49 | .kt { color: #458; font-weight: bold } // Keyword.Type

50 | .m { color: #099 } // Literal.Number

51 | .s { color: #d14 } // Literal.String

52 | .na { color: #008080 } // Name.Attribute

53 | .nb { color: #0086B3 } // Name.Builtin

54 | .nc { color: #458; font-weight: bold } // Name.Class

55 | .no { color: #008080 } // Name.Constant

56 | .ni { color: #800080 } // Name.Entity

57 | .ne { color: #900; font-weight: bold } // Name.Exception

58 | .nf { color: #900; font-weight: bold } // Name.Function

59 | .nn { color: #555 } // Name.Namespace

60 | .nt { color: #000080 } // Name.Tag

61 | .nv { color: #008080 } // Name.Variable

62 | .ow { font-weight: bold } // Operator.Word

63 | .w { color: #bbb } // Text.Whitespace

64 | .mf { color: #099 } // Literal.Number.Float

65 | .mh { color: #099 } // Literal.Number.Hex

66 | .mi { color: #099 } // Literal.Number.Integer

67 | .mo { color: #099 } // Literal.Number.Oct

68 | .sb { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Backtick

69 | .sc { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Char

70 | .sd { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Doc

71 | .s2 { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Double

72 | .se { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Escape

73 | .sh { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Heredoc

74 | .si { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Interpol

75 | .sx { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Other

76 | .sr { color: #009926 } // Literal.String.Regex

77 | .s1 { color: #d14 } // Literal.String.Single

78 | .ss { color: #990073 } // Literal.String.Symbol

79 | .bp { color: #999 } // Name.Builtin.Pseudo

80 | .vc { color: #008080 } // Name.Variable.Class

81 | .vg { color: #008080 } // Name.Variable.Global

82 | .vi { color: #008080 } // Name.Variable.Instance

83 | .il { color: #099 } // Literal.Number.Integer.Long

84 | }

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/assets/fonts/OFL.txt:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | Copyright 2017 The EB Garamond Project Authors (https://github.com/octaviopardo/EBGaramond12)

2 |

3 | This Font Software is licensed under the SIL Open Font License, Version 1.1.

4 | This license is copied below, and is also available with a FAQ at:

5 | http://scripts.sil.org/OFL

6 |

7 |

8 | -----------------------------------------------------------

9 | SIL OPEN FONT LICENSE Version 1.1 - 26 February 2007

10 | -----------------------------------------------------------

11 |

12 | PREAMBLE

13 | The goals of the Open Font License (OFL) are to stimulate worldwide

14 | development of collaborative font projects, to support the font creation

15 | efforts of academic and linguistic communities, and to provide a free and

16 | open framework in which fonts may be shared and improved in partnership

17 | with others.

18 |

19 | The OFL allows the licensed fonts to be used, studied, modified and

20 | redistributed freely as long as they are not sold by themselves. The

21 | fonts, including any derivative works, can be bundled, embedded,

22 | redistributed and/or sold with any software provided that any reserved

23 | names are not used by derivative works. The fonts and derivatives,

24 | however, cannot be released under any other type of license. The

25 | requirement for fonts to remain under this license does not apply

26 | to any document created using the fonts or their derivatives.

27 |

28 | DEFINITIONS

29 | "Font Software" refers to the set of files released by the Copyright

30 | Holder(s) under this license and clearly marked as such. This may

31 | include source files, build scripts and documentation.

32 |

33 | "Reserved Font Name" refers to any names specified as such after the

34 | copyright statement(s).

35 |

36 | "Original Version" refers to the collection of Font Software components as

37 | distributed by the Copyright Holder(s).

38 |

39 | "Modified Version" refers to any derivative made by adding to, deleting,

40 | or substituting -- in part or in whole -- any of the components of the

41 | Original Version, by changing formats or by porting the Font Software to a

42 | new environment.

43 |

44 | "Author" refers to any designer, engineer, programmer, technical

45 | writer or other person who contributed to the Font Software.

46 |

47 | PERMISSION & CONDITIONS

48 | Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining

49 | a copy of the Font Software, to use, study, copy, merge, embed, modify,

50 | redistribute, and sell modified and unmodified copies of the Font

51 | Software, subject to the following conditions:

52 |

53 | 1) Neither the Font Software nor any of its individual components,

54 | in Original or Modified Versions, may be sold by itself.

55 |

56 | 2) Original or Modified Versions of the Font Software may be bundled,

57 | redistributed and/or sold with any software, provided that each copy

58 | contains the above copyright notice and this license. These can be

59 | included either as stand-alone text files, human-readable headers or

60 | in the appropriate machine-readable metadata fields within text or

61 | binary files as long as those fields can be easily viewed by the user.

62 |

63 | 3) No Modified Version of the Font Software may use the Reserved Font

64 | Name(s) unless explicit written permission is granted by the corresponding

65 | Copyright Holder. This restriction only applies to the primary font name as

66 | presented to the users.

67 |

68 | 4) The name(s) of the Copyright Holder(s) or the Author(s) of the Font

69 | Software shall not be used to promote, endorse or advertise any

70 | Modified Version, except to acknowledge the contribution(s) of the

71 | Copyright Holder(s) and the Author(s) or with their explicit written

72 | permission.

73 |

74 | 5) The Font Software, modified or unmodified, in part or in whole,

75 | must be distributed entirely under this license, and must not be

76 | distributed under any other license. The requirement for fonts to

77 | remain under this license does not apply to any document created

78 | using the Font Software.

79 |

80 | TERMINATION

81 | This license becomes null and void if any of the above conditions are

82 | not met.

83 |

84 | DISCLAIMER

85 | THE FONT SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND,

86 | EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO ANY WARRANTIES OF

87 | MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT

88 | OF COPYRIGHT, PATENT, TRADEMARK, OR OTHER RIGHT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE

89 | COPYRIGHT HOLDER BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY,

90 | INCLUDING ANY GENERAL, SPECIAL, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL

91 | DAMAGES, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING

92 | FROM, OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THE FONT SOFTWARE OR FROM

93 | OTHER DEALINGS IN THE FONT SOFTWARE.

94 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/README.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | layout: page

3 | title: "Hitchens"

4 | ---

5 |

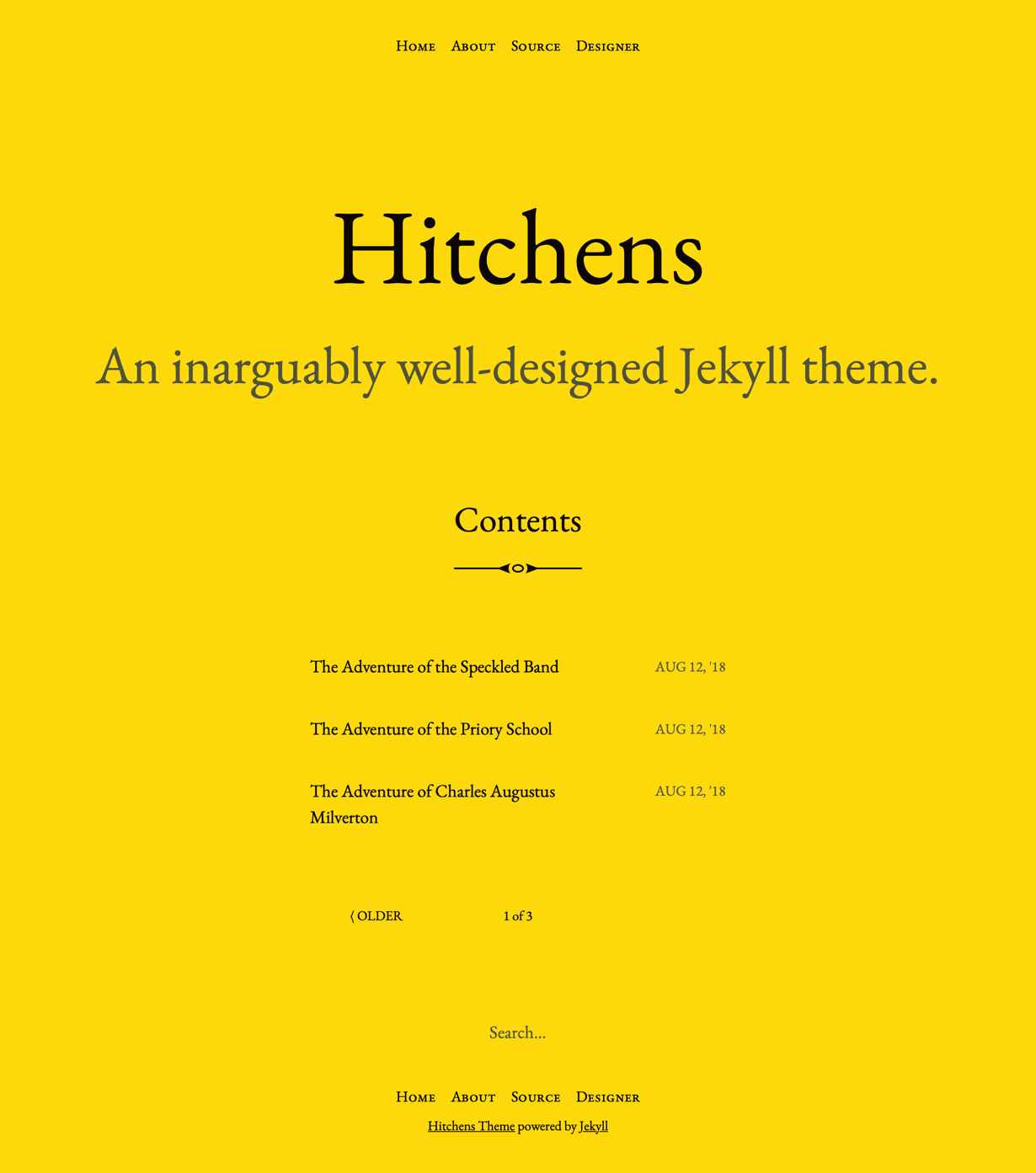

6 | An inarguably well-designed [Jekyll](http://jekyllrb.com) theme by [Pat Dryburgh](https://patdryburgh.com).

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 | Undoubtably one of the great minds of our time, [Christopher Hitchens](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Hitchens) challenged his readers to think deeply on topics of politics, religion, war, and science. This Jekyll theme's design is inspired by the trade paperback version his book, [Arguably](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arguably), and is dedicated to his memory.

11 |

12 | Not comfortable with Jekyll? This theme has also been ported to other platforms:

13 |

14 | - [Hitchens for Hugo](https://github.com/pimoore/microdotblog-hitchens) by Pete Moore (also available to be used on [Micro.blog](https://micro.blog))

15 | - [Hitchens for Eleventy](https://github.com/shellen/hitchens-eleventy) by Jason Shellen

16 |

17 | **The following instructions pertain to Hitchens for Jekyll.**

18 |

19 | ## Quick Start

20 |

21 | This theme is, itself, a Jekyll blog, meaning the code base you see has everything you need to run a Jekyll powered blog!

22 |

23 | To get started quickly, follow the instructions below:

24 |

25 | 1. Click the `Fork` button at the top of [the repository](https://github.com/patdryburgh/hitchens/);

26 | 2. Go to your forked repo's `Settings` screen;

27 | 3. Scroll down to the `GitHub Pages` section;

28 | 4. Under `Source`, select the `Master` branch;

29 | 5. Hit `Save`.

30 | 6. Follow [Jekyll's instructions to configure your new Jekyll site](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/configuration/).

31 |

32 | ## Manual Installation

33 |

34 | If you've already created your Jekyll site or are comfortable with the command line, you can follow [Jekyll's Quickstart instructions](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/) add this line to your Jekyll site's `Gemfile`:

35 |

36 | ```ruby

37 | gem "hitchens-theme"

38 | ```

39 |

40 | And add the following lines to your Jekyll site's `_config.yml`:

41 |

42 | ```yaml

43 | theme: hitchens-theme

44 | ```

45 |

46 | Depending on your [site's configuration](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/configuration/options/), you may also need to add:

47 |

48 | ```yaml

49 | ignore_theme_config: true

50 | ```

51 |

52 | And then on the command line, execute:

53 |

54 | $ bundle

55 |

56 | Or install the theme yourself as:

57 |

58 | $ gem install hitchens-theme

59 |

60 | ## Usage

61 |

62 | ### Home Layout

63 |

64 | The `home` layout presents a list of articles ordered chronologically. The theme uses [Jekyll's built-in pagination](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/pagination/#enable-pagination) which can be configured in your `_config.yml` file.

65 |

66 | The masthead of the home page is derived from the `title` and `description` set in your site's `_config.yml` file.

67 |

68 | #### Navigation

69 |

70 | To include a navigation menu in your site's masthead and footer:

71 |

72 | 1. Create a `_data` directory in the root of your site.

73 | 2. Add a `menu.yml` file to the `_data` directory.

74 | 3. Use the following format to list your menu items:

75 |

76 | ```

77 | - title: About

78 | url: /about.html

79 |

80 | - title: Source

81 | url: https://github.com/patdryburgh/hitchens

82 | ```

83 |

84 | Be sure to start your `url`s with a `/`.

85 |

86 | #### Pagination

87 |

88 | To paginate your posts, add the following line to your site's `Gemfile`:

89 |

90 | ```

91 | gem "jekyll-paginate"

92 | ```

93 |

94 | Then, add the following lines to your site's `_config.yml` file:

95 |

96 | ```

97 | plugins:

98 | - jekyll-paginate

99 |

100 | paginate: 20

101 | paginate_path: "/page/:num/"

102 | ```

103 |

104 | You can set the `paginate` and `paginate_path` settings to whatever best suits you.

105 |

106 | #### Excerpts

107 |

108 | To show [excerpts](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/posts/#post-excerpts) of your blog posts on the home page, add the following settings to your site's `_config.yml` file:

109 |

110 | ```

111 | show_excerpts: true

112 | ```

113 |

114 | By default, excerpts that have more than 140 characters will be truncated to 20 words. In order to override the number of words you'd like to show for your excerpts, add the following setting to your site's `_config.yml` file:

115 |

116 | ```

117 | excerpt_length: 20

118 | ```

119 |

120 | To disable excerpt truncation entirely, simply set `excerpt_length` to `0` in your site's `_config.yml` file, like so:

121 |

122 | ```

123 | excerpt_length: 0

124 | ```

125 |

126 | If you do this, the theme will still respect Jekyll's `excerpt_separator` feature as [described in the Jekyll documentation](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/posts/#post-excerpts).

127 |

128 |

129 | #### Title-less Posts

130 |

131 | If you want to publish posts that don't have a title, add the following setting to the [front matter](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/frontmatter/) of the post:

132 |

133 | ```

134 | title: ""

135 | ```

136 |

137 | When you do this, the home page will display a truncated [excerpt](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/posts/#post-excerpts) of the first paragraph of your post.

138 |

139 | Note that setting `excerpt_length` in your site's `_config.yml` file will set the length of _all_ excerpts, regardless of whether the post has a title or not. For posts with a title, the excerpt will appear under the title and slightly lighter. For title-less posts, the excerpt will appear as if it were a title.

140 |

141 | ### Post Layout

142 |

143 | A sparsely decorated layout designed to present long-form writing in a manner that's pleasing to read.

144 |

145 | To use the post layout, add the following to your post's [front matter](https://jekyllrb.com/docs/frontmatter/):

146 |

147 | ```

148 | layout: post

149 | ```

150 |

151 | ### Icons

152 |

153 | The [JSON Feed spec](https://jsonfeed.org/version/1) states that feeds should include an icon. To add your icon, add the following line in your site's `_config.yml` file:

154 |

155 | ```

156 | feed_icon: /assets/images/icon-512.png

157 | ```

158 |

159 | Then, replace the `/assets/images/icon-512.png` file with your own image.

160 |

161 | ### Credits

162 |

163 | The theme credits that appear at the bottom of each page can be turned off by including the following line in your site's `_config.yml` file:

164 |

165 | ```

166 | hide_credits: true

167 | ```

168 |

169 | ### Search

170 |

171 | The theme uses a [custom DuckDuckGo Search Form](https://ddg.patdryburgh.com) that can be turned off by including the following line in your site's `_config.yml` file:

172 |

173 | ```

174 | hide_search: true

175 | ```

176 |

177 | ### Font

178 |

179 | I spent a good amount of time trying to identify the font used on the front cover of the trade paperback version of Arguably. Unfortunately, I failed to accurately identify the exact font used. If you happen to know what font is used on the book cover, I would appreciate you [letting me know](mailto:hello@patdryburgh.com) :)

180 |

181 | The theme includes a version of [EB Garamond](https://fonts.google.com/specimen/EB+Garamond), designed by Georg Duffner and Octavio Pardo. It's the closest alternative I could come up with that included an open license to include with the theme.

182 |

183 | A [copy of the license](https://github.com/patdryburgh/hitchens/blob/master/assets/fonts/OFL.txt) has been included in the `assets` folder and must be included with any distributions of this theme that include the EB Garamond font files.

184 |

185 | ## Contributing & Requesting Features

186 |

187 | Bug reports, feature requests, and pull requests are welcome on GitHub at [https://github.com/patdryburgh/hitchens](https://github.com/patdryburgh/hitchens).

188 |

189 | This project is intended to be a safe, welcoming space for collaboration, and contributors are expected to adhere to the [Contributor Covenant](http://contributor-covenant.org) code of conduct.

190 |

191 | ## Development

192 |

193 | To set up your environment to develop this theme, run `bundle install`.

194 |

195 | The theme is setup just like a normal Jekyll site. To test the theme, run `bundle exec jekyll serve` and open your browser at `http://localhost:4000`. This starts a Jekyll server using the theme. Add pages, documents, data, etc. like normal to test the theme's contents. As you make modifications to the theme and to your content, your site will regenerate and you should see the changes in the browser after a refresh, just like normal.

196 |

197 | ## License

198 |

199 | The code for this theme is available as open source under the terms of the [MIT License](https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT).

200 |

201 | The font, EB Garamond, is Copyright 2017 The EB Garamond Project Authors and licensed under the [SIL Open Font License Version 1.1](https://github.com/patdryburgh/hitchens/blob/master/assets/fonts/OFL.txt).

202 |

203 | Graphics are released to the public domain.

204 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/_posts/2012-07-24-the-adventure-of-the-veiled-lodger.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | title: ""

3 | layout: post

4 | author: "Arthur Conan Doyle"

5 | categories: literature

6 | ---

7 |

8 | When one considers that Mr. Sherlock Holmes was in active practice for twenty-three years, and that during seventeen of these I was allowed to cooperate with him and to keep notes of his doings, it will be clear that I have a mass of material at my command. The problem has always been not to find but to choose. There is the long row of year-books which fill a shelf, and there are the dispatch-cases filled with documents, a perfect quarry for the student not only of crime but of the social and official scandals of the late Victorian era. Concerning these latter, I may say that the writers of agonized letters, who beg that the honour of their families or the reputation of famous forebears may not be touched, have nothing to fear. The discretion and high sense of professional honour which have always distinguished my friend are still at work in the choice of these memoirs, and no confidence will be abused. I deprecate, however, in the strongest way the attempts which have been made lately to get at and to destroy these papers. The source of these outrages is known, and if they are repeated I have Mr. Holmes's authority for saying that the whole story concerning the politician, the lighthouse, and the trained cormorant will be given to the public. There is at least one reader who will understand.

9 |

10 | It is not reasonable to suppose that every one of these cases gave Holmes the opportunity of showing those curious gifts of instinct and observation which I have endeavoured to set forth in these memoirs. Sometimes he had with much effort to pick the fruit, sometimes it fell easily into his lap. But the most terrible human tragedies were often involved in those cases which brought him the fewest personal opportunities, and it is one of these which I now desire to record. In telling it, I have made a slight change of name and place, but otherwise the facts are as stated.

11 |

12 | One forenoon—it was late in 1896—I received a hurried note from Holmes asking for my attendance. When I arrived I found him seated in a smoke-laden atmosphere, with an elderly, motherly woman of the buxom landlady type in the corresponding chair in front of him.

13 |

14 | “This is Mrs. Merrilow, of South Brixton,” said my friend with a wave of the hand. “Mrs. Merrilow does not object to tobacco, Watson, if you wish to indulge your filthy habits. Mrs. Merrilow has an interesting story to tell which may well lead to further developments in which your presence may be useful.”

15 |

16 | “Anything I can do—”

17 |

18 | “You will understand, Mrs. Merrilow, that if I come to Mrs. Ronder I should prefer to have a witness. You will make her understand that before we arrive.”

19 |

20 | “Lord bless you, Mr. Holmes,” said our visitor, “she is that anxious to see you that you might bring the whole parish at your heels!”

21 |

22 | “Then we shall come early in the afternoon. Let us see that we have our facts correct before we start. If we go over them it will help Dr. Watson to understand the situation. You say that Mrs. Ronder has been your lodger for seven years and that you have only once seen her face.”

23 |

24 | “And I wish to God I had not!” said Mrs. Merrilow.

25 |

26 | “It was, I understand, terribly mutilated.”

27 |

28 | “Well, Mr. Holmes, you would hardly say it was a face at all. That's how it looked. Our milkman got a glimpse of her once peeping out of the upper window, and he dropped his tin and the milk all over the front garden. That is the kind of face it is. When I saw her—I happened on her unawares—she covered up quick, and then she said, ‘Now, Mrs. Merrilow, you know at last why it is that I never raise my veil.’”

29 |

30 | “Do you know anything about her history?”

31 |

32 | “Nothing at all.”

33 |

34 | “Did she give references when she came?”

35 |

36 | “No, sir, but she gave hard cash, and plenty of it. A quarter's rent right down on the table in advance and no arguing about terms. In these times a poor woman like me can't afford to turn down a chance like that.”

37 |

38 | “Did she give any reason for choosing your house?”

39 |

40 | “Mine stands well back from the road and is more private than most. Then, again, I only take the one, and I have no family of my own. I reckon she had tried others and found that mine suited her best. It's privacy she is after, and she is ready to pay for it.”

41 |

42 | “You say that she never showed her face from first to last save on the one accidental occasion. Well, it is a very remarkable story, most remarkable, and I don't wonder that you want it examined.”

43 |

44 | “I don't, Mr. Holmes. I am quite satisfied so long as I get my rent. You could not have a quieter lodger, or one who gives less trouble.”

45 |

46 | “Then what has brought matters to a head?”

47 |

48 | “Her health, Mr. Holmes. She seems to be wasting away. And there's something terrible on her mind. ‘Murder!’ she cries. ‘Murder!’ And once I heard her: ‘You cruel beast! You monster!’ she cried. It was in the night, and it fair rang through the house and sent the shivers through me. So I went to her in the morning. ‘Mrs. Ronder,’ I says, ‘if you have anything that is troubling your soul, there's the clergy,’ I says, ‘and there's the police. Between them you should get some help.’ ‘For God's sake, not the police!’ says she, ‘and the clergy can't change what is past. And yet,’ she says, ‘it would ease my mind if someone knew the truth before I died.’ ‘Well,’ says I, ‘if you won't have the regulars, there is this detective man what we read about’—beggin' your pardon, Mr. Holmes. And she, she fair jumped at it. ‘That's the man,’ says she. ‘I wonder I never thought of it before. Bring him here, Mrs. Merrilow, and if he won't come, tell him I am the wife of Ronder's wild beast show. Say that, and give him the name Abbas Parva. Here it is as she wrote it, Abbas Parva. ‘That will bring him if he's the man I think he is.’”

49 |

50 | “And it will, too,” remarked Holmes. “Very good, Mrs. Merrilow. I should like to have a little chat with Dr. Watson. That will carry us till lunch-time. About three o'clock you may expect to see us at your house in Brixton.”

51 |

52 | Our visitor had no sooner waddled out of the room—no other verb can describe Mrs. Merrilow's method of progression—than Sherlock Holmes threw himself with fierce energy upon the pile of commonplace books in the corner. For a few minutes there was a constant swish of the leaves, and then with a grunt of satisfaction he came upon what he sought. So excited was he that he did not rise, but sat upon the floor like some strange Buddha, with crossed legs, the huge books all round him, and one open upon his knees.

53 |

54 | “The case worried me at the time, Watson. Here are my marginal notes to prove it. I confess that I could make nothing of it. And yet I was convinced that the coroner was wrong. Have you no recollection of the Abbas Parva tragedy?”

55 |

56 | “None, Holmes.”

57 |

58 | “And yet you were with me then. But certainly my own impression was very superficial. For there was nothing to go by, and none of the parties had engaged my services. Perhaps you would care to read the papers?”

59 |

60 | “Could you not give me the points?”

61 |

62 | “That is very easily done. It will probably come back to your memory as I talk. Ronder, of course, was a household word. He was the rival of Wombwell, and of Sanger, one of the greatest showmen of his day. There is evidence, however, that he took to drink, and that both he and his show were on the down grade at the time of the great tragedy. The caravan had halted for the night at Abbas Parva, which is a small village in Berkshire, when this horror occurred. They were on their way to Wimbledon, travelling by road, and they were simply camping and not exhibiting, as the place is so small a one that it would not have paid them to open.

63 |

64 | “They had among their exhibits a very fine North African lion. Sahara King was its name, and it was the habit, both of Ronder and his wife, to give exhibitions inside its cage. Here, you see, is a photograph of the performance by which you will perceive that Ronder was a huge porcine person and that his wife was a very magnificent woman. It was deposed at the inquest that there had been some signs that the lion was dangerous, but, as usual, familiarity begat contempt, and no notice was taken of the fact.

65 |

66 | “It was usual for either Ronder or his wife to feed the lion at night. Sometimes one went, sometimes both, but they never allowed anyone else to do it, for they believed that so long as they were the food-carriers he would regard them as benefactors and would never molest them. On this particular night, seven years ago, they both went, and a very terrible happening followed, the details of which have never been made clear.

67 |

68 | “It seems that the whole camp was roused near midnight by the roars of the animal and the screams of the woman. The different grooms and employees rushed from their tents, carrying lanterns, and by their light an awful sight was revealed. Ronder lay, with the back of his head crushed in and deep claw-marks across his scalp, some ten yards from the cage, which was open. Close to the door of the cage lay Mrs. Ronder upon her back, with the creature squatting and snarling above her. It had torn her face in such a fashion that it was never thought that she could live. Several of the circus men, headed by Leonardo, the strong man, and Griggs, the clown, drove the creature off with poles, upon which it sprang back into the cage and was at once locked in. How it had got loose was a mystery. It was conjectured that the pair intended to enter the cage, but that when the door was loosed the creature bounded out upon them. There was no other point of interest in the evidence save that the woman in a delirium of agony kept screaming, ‘Coward! Coward!’ as she was carried back to the van in which they lived. It was six months before she was fit to give evidence, but the inquest was duly held, with the obvious verdict of death from misadventure.”

69 |

70 | “What alternative could be conceived?” said I.

71 |

72 | “You may well say so. And yet there were one or two points which worried young Edmunds, of the Berkshire Constabulary. A smart lad that! He was sent later to Allahabad. That was how I came into the matter, for he dropped in and smoked a pipe or two over it.”

73 |

74 | “A thin, yellow-haired man?”

75 |

76 | “Exactly. I was sure you would pick up the trail presently.”

77 |

78 | “But what worried him?”

79 |

80 | “Well, we were both worried. It was so deucedly difficult to reconstruct the affair. Look at it from the lion's point of view. He is liberated. What does he do? He takes half a dozen bounds forward, which brings him to Ronder. Ronder turns to fly—the claw-marks were on the back of his head—but the lion strikes him down. Then, instead of bounding on and escaping, he returns to the woman, who was close to the cage, and he knocks her over and chews her face up. Then, again, those cries of hers would seem to imply that her husband had in some way failed her. What could the poor devil have done to help her? You see the difficulty?”

81 |

82 | “Quite.”

83 |

84 | “And then there was another thing. It comes back to me now as I think it over. There was some evidence that just at the time the lion roared and the woman screamed, a man began shouting in terror.”

85 |

86 | “This man Ronder, no doubt.”

87 |

88 | “Well, if his skull was smashed in you would hardly expect to hear from him again. There were at least two witnesses who spoke of the cries of a man being mingled with those of a woman.”

89 |

90 | “I should think the whole camp was crying out by then. As to the other points, I think I could suggest a solution.”

91 |

92 | “I should be glad to consider it.”

93 |

94 | “The two were together, ten yards from the cage, when the lion got loose. The man turned and was struck down. The woman conceived the idea of getting into the cage and shutting the door. It was her only refuge. She made for it, and just as she reached it the beast bounded after her and knocked her over. She was angry with her husband for having encouraged the beast's rage by turning. If they had faced it they might have cowed it. Hence her cries of ‘Coward!’”

95 |

96 | “Brilliant, Watson! Only one flaw in your diamond.”

97 |

98 | “What is the flaw, Holmes?”

99 |

100 | “If they were both ten paces from the cage, how came the beast to get loose?”

101 |

102 | “Is it possible that they had some enemy who loosed it?”

103 |

104 | “And why should it attack them savagely when it was in the habit of playing with them, and doing tricks with them inside the cage?”

105 |

106 | “Possibly the same enemy had done something to enrage it.”

107 |

108 | Holmes looked thoughtful and remained in silence for some moments.

109 |

110 | “Well, Watson, there is this to be said for your theory. Ronder was a man of many enemies. Edmunds told me that in his cups he was horrible. A huge bully of a man, he cursed and slashed at everyone who came in his way. I expect those cries about a monster, of which our visitor has spoken, were nocturnal reminiscences of the dear departed. However, our speculations are futile until we have all the facts. There is a cold partridge on the sideboard, Watson, and a bottle of Montrachet. Let us renew our energies before we make a fresh call upon them.”

111 |

112 | When our hansom deposited us at the house of Mrs. Merrilow, we found that plump lady blocking up the open door of her humble but retired abode. It was very clear that her chief preoccupation was lest she should lose a valuable lodger, and she implored us, before showing us up, to say and do nothing which could lead to so undesirable an end. Then, having reassured her, we followed her up the straight, badly carpeted staircase and were shown into the room of the mysterious lodger.

113 |

114 | It was a close, musty, ill-ventilated place, as might be expected, since its inmate seldom left it. From keeping beasts in a cage, the woman seemed, by some retribution of fate, to have become herself a beast in a cage. She sat now in a broken armchair in the shadowy corner of the room. Long years of inaction had coarsened the lines of her figure, but at some period it must have been beautiful, and was still full and voluptuous. A thick dark veil covered her face, but it was cut off close at her upper lip and disclosed a perfectly shaped mouth and a delicately rounded chin. I could well conceive that she had indeed been a very remarkable woman. Her voice, too, was well modulated and pleasing.

115 |

116 | “My name is not unfamiliar to you, Mr. Holmes,” said she. “I thought that it would bring you.”

117 |

118 | “That is so, madam, though I do not know how you are aware that I was interested in your case.”

119 |

120 | “I learned it when I had recovered my health and was examined by Mr. Edmunds, the county detective. I fear I lied to him. Perhaps it would have been wiser had I told the truth.”

121 |

122 | “It is usually wiser to tell the truth. But why did you lie to him?”

123 |

124 | “Because the fate of someone else depended upon it. I know that he was a very worthless being, and yet I would not have his destruction upon my conscience. We had been so close—so close!”

125 |

126 | “But has this impediment been removed?”

127 |

128 | “Yes, sir. The person that I allude to is dead.”

129 |

130 | “Then why should you not now tell the police anything you know?”

131 |

132 | “Because there is another person to be considered. That other person is myself. I could not stand the scandal and publicity which would come from a police examination. I have not long to live, but I wish to die undisturbed. And yet I wanted to find one man of judgment to whom I could tell my terrible story, so that when I am gone all might be understood.”

133 |

134 | “You compliment me, madam. At the same time, I am a responsible person. I do not promise you that when you have spoken I may not myself think it my duty to refer the case to the police.”

135 |

136 | “I think not, Mr. Holmes. I know your character and methods too well, for I have followed your work for some years. Reading is the only pleasure which fate has left me, and I miss little which passes in the world. But in any case, I will take my chance of the use which you may make of my tragedy. It will ease my mind to tell it.”

137 |

138 | “My friend and I would be glad to hear it.”

139 |

140 | The woman rose and took from a drawer the photograph of a man. He was clearly a professional acrobat, a man of magnificent physique, taken with his huge arms folded across his swollen chest and a smile breaking from under his heavy moustache—the self-satisfied smile of the man of many conquests.

141 |

142 | “That is Leonardo,” she said.

143 |

144 | “Leonardo, the strong man, who gave evidence?”

145 |

146 | “The same. And this—this is my husband.”

147 |

148 | It was a dreadful face—a human pig, or rather a human wild boar, for it was formidable in its bestiality. One could imagine that vile mouth champing and foaming in its rage, and one could conceive those small, vicious eyes darting pure malignancy as they looked forth upon the world. Ruffian, bully, beast—it was all written on that heavy-jowled face.

149 |

150 | “Those two pictures will help you, gentlemen, to understand the story. I was a poor circus girl brought up on the sawdust, and doing springs through the hoop before I was ten. When I became a woman this man loved me, if such lust as his can be called love, and in an evil moment I became his wife. From that day I was in hell, and he the devil who tormented me. There was no one in the show who did not know of his treatment. He deserted me for others. He tied me down and lashed me with his riding-whip when I complained. They all pitied me and they all loathed him, but what could they do? They feared him, one and all. For he was terrible at all times, and murderous when he was drunk. Again and again he was had up for assault, and for cruelty to the beasts, but he had plenty of money and the fines were nothing to him. The best men all left us, and the show began to go downhill. It was only Leonardo and I who kept it up—with little Jimmy Griggs, the clown. Poor devil, he had not much to be funny about, but he did what he could to hold things together.

151 |

152 | “Then Leonardo came more and more into my life. You see what he was like. I know now the poor spirit that was hidden in that splendid body, but compared to my husband he seemed like the angel Gabriel. He pitied me and helped me, till at last our intimacy turned to love—deep, deep, passionate love, such love as I had dreamed of but never hoped to feel. My husband suspected it, but I think that he was a coward as well as a bully, and that Leonardo was the one man that he was afraid of. He took revenge in his own way by torturing me more than ever. One night my cries brought Leonardo to the door of our van. We were near tragedy that night, and soon my lover and I understood that it could not be avoided. My husband was not fit to live. We planned that he should die.

153 |

154 | “Leonardo had a clever, scheming brain. It was he who planned it. I do not say that to blame him, for I was ready to go with him every inch of the way. But I should never have had the wit to think of such a plan. We made a club—Leonardo made it—and in the leaden head he fastened five long steel nails, the points outward, with just such a spread as the lion's paw. This was to give my husband his death-blow, and yet to leave the evidence that it was the lion which we would loose who had done the deed.

155 |

156 | “It was a pitch-dark night when my husband and I went down, as was our custom, to feed the beast. We carried with us the raw meat in a zinc pail. Leonardo was waiting at the corner of the big van which we should have to pass before we reached the cage. He was too slow, and we walked past him before he could strike, but he followed us on tiptoe and I heard the crash as the club smashed my husband's skull. My heart leaped with joy at the sound. I sprang forward, and I undid the catch which held the door of the great lion's cage.

157 |

158 | “And then the terrible thing happened. You may have heard how quick these creatures are to scent human blood, and how it excites them. Some strange instinct had told the creature in one instant that a human being had been slain. As I slipped the bars it bounded out and was on me in an instant. Leonardo could have saved me. If he had rushed forward and struck the beast with his club he might have cowed it. But the man lost his nerve. I heard him shout in his terror, and then I saw him turn and fly. At the same instant the teeth of the lion met in my face. Its hot, filthy breath had already poisoned me and I was hardly conscious of pain. With the palms of my hands I tried to push the great steaming, blood-stained jaws away from me, and I screamed for help. I was conscious that the camp was stirring, and then dimly I remembered a group of men. Leonardo, Griggs, and others, dragging me from under the creature's paws. That was my last memory, Mr. Holmes, for many a weary month. When I came to myself and saw myself in the mirror, I cursed that lion—oh, how I cursed him!—not because he had torn away my beauty but because he had not torn away my life. I had but one desire, Mr. Holmes, and I had enough money to gratify it. It was that I should cover myself so that my poor face should be seen by none, and that I should dwell where none whom I had ever known should find me. That was all that was left to me to do—and that is what I have done. A poor wounded beast that has crawled into its hole to die—that is the end of Eugenia Ronder.”

159 |

160 | We sat in silence for some time after the unhappy woman had told her story. Then Holmes stretched out his long arm and patted her hand with such a show of sympathy as I had seldom known him to exhibit.

161 |

162 | “Poor girl!” he said. “Poor girl! The ways of fate are indeed hard to understand. If there is not some compensation hereafter, then the world is a cruel jest. But what of this man Leonardo?”

163 |

164 | “I never saw him or heard from him again. Perhaps I have been wrong to feel so bitterly against him. He might as soon have loved one of the freaks whom we carried round the country as the thing which the lion had left. But a woman's love is not so easily set aside. He had left me under the beast's claws, he had deserted me in my need, and yet I could not bring myself to give him to the gallows. For myself, I cared nothing what became of me. What could be more dreadful than my actual life? But I stood between Leonardo and his fate.”

165 |

166 | “And he is dead?”

167 |

168 | “He was drowned last month when bathing near Margate. I saw his death in the paper.”

169 |

170 | “And what did he do with this five-clawed club, which is the most singular and ingenious part of all your story?”

171 |

172 | “I cannot tell, Mr. Holmes. There is a chalk-pit by the camp, with a deep green pool at the base of it. Perhaps in the depths of that pool—”

173 |

174 | “Well, well, it is of little consequence now. The case is closed.”

175 |

176 | “Yes,” said the woman, “the case is closed.”

177 |

178 | We had risen to go, but there was something in the woman's voice which arrested Holmes's attention. He turned swiftly upon her.

179 |

180 | “Your life is not your own,” he said. “Keep your hands off it.”

181 |

182 | “What use is it to anyone?”

183 |

184 | “How can you tell? The example of patient suffering is in itself the most precious of all lessons to an impatient world.”

185 |

186 | The woman's answer was a terrible one. She raised her veil and stepped forward into the light.

187 |

188 | “I wonder if you would bear it,” she said.

189 |

190 | It was horrible. No words can describe the framework of a face when the face itself is gone. Two living and beautiful brown eyes looking sadly out from that grisly ruin did but make the view more awful. Holmes held up his hand in a gesture of pity and protest, and together we left the room.

191 |

192 | Two days later, when I called upon my friend, he pointed with some pride to a small blue bottle upon his mantelpiece. I picked it up. There was a red poison label. A pleasant almondy odour rose when I opened it.

193 |

194 | “Prussic acid?” said I.

195 |

196 | “Exactly. It came by post. ‘I send you my temptation. I will follow your advice.’ That was the message. I think, Watson, we can guess the name of the brave woman who sent it.”

197 |

198 | [Text taken from here](http://sherlock-holm.es/stories/html/veil.html)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/_posts/2012-06-09-the-adventure-of-the-dying-detective.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ---

2 | layout: post

3 | title: "The Adventure of the Dying Detective"

4 | author: "Arthur Conan Doyle"

5 | categories: literature

6 | author: Arthur Conan Doyle

7 | ---

8 |

9 | Mrs. Hudson, the landlady of Sherlock Holmes, was a long-suffering woman. Not only was her first-floor flat invaded at all hours by throngs of singular and often undesirable characters but her remarkable lodger showed an eccentricity and irregularity in his life which must have sorely tried her patience. His incredible untidiness, his addiction to music at strange hours, his occasional revolver practice within doors, his weird and often malodorous scientific experiments, and the atmosphere of violence and danger which hung around him made him the very worst tenant in London. On the other hand, his payments were princely. I have no doubt that the house might have been purchased at the price which Holmes paid for his rooms during the years that I was with him.

10 |

11 | The landlady stood in the deepest awe of him and never dared to interfere with him, however outrageous his proceedings might seem. She was fond of him, too, for he had a remarkable gentleness and courtesy in his dealings with women. He disliked and distrusted the sex, but he was always a chivalrous opponent. Knowing how genuine was her regard for him, I listened earnestly to her story when she came to my rooms in the second year of my married life and told me of the sad condition to which my poor friend was reduced.

12 |

13 | “He's dying, Dr. Watson,” said she. “For three days he has been sinking, and I doubt if he will last the day. He would not let me get a doctor. This morning when I saw his bones sticking out of his face and his great bright eyes looking at me I could stand no more of it. ‘With your leave or without it, Mr. Holmes, I am going for a doctor this very hour,’ said I. ‘Let it be Watson, then,’ said he. I wouldn't waste an hour in coming to him, sir, or you may not see him alive.”

14 |

15 | I was horrified for I had heard nothing of his illness. I need not say that I rushed for my coat and my hat. As we drove back I asked for the details.

16 |

17 | “There is little I can tell you, sir. He has been working at a case down at Rotherhithe, in an alley near the river, and he has brought this illness back with him. He took to his bed on Wednesday afternoon and has never moved since. For these three days neither food nor drink has passed his lips.”

18 |

19 | “Good God! Why did you not call in a doctor?”

20 |

21 | “He wouldn't have it, sir. You know how masterful he is. I didn't dare to disobey him. But he's not long for this world, as you'll see for yourself the moment that you set eyes on him.”

22 |

23 | He was indeed a deplorable spectacle. In the dim light of a foggy November day the sick room was a gloomy spot, but it was that gaunt, wasted face staring at me from the bed which sent a chill to my heart. His eyes had the brightness of fever, there was a hectic flush upon either cheek, and dark crusts clung to his lips; the thin hands upon the coverlet twitched incessantly, his voice was croaking and spasmodic. He lay listlessly as I entered the room, but the sight of me brought a gleam of recognition to his eyes.

24 |

25 | “Well, Watson, we seem to have fallen upon evil days,” said he in a feeble voice, but with something of his old carelessness of manner.

26 |

27 | “My dear fellow!” I cried, approaching him.

28 |

29 | “Stand back! Stand right back!” said he with the sharp imperiousness which I had associated only with moments of crisis. “If you approach me, Watson, I shall order you out of the house.”

30 |

31 | “But why?”

32 |

33 | “Because it is my desire. Is that not enough?”

34 |

35 | Yes, Mrs. Hudson was right. He was more masterful than ever. It was pitiful, however, to see his exhaustion.

36 |

37 | “I only wished to help,” I explained.

38 |

39 | “Exactly! You will help best by doing what you are told.”

40 |

41 | “Certainly, Holmes.”

42 |

43 | He relaxed the austerity of his manner.

44 |

45 | “You are not angry?” he asked, gasping for breath.

46 |

47 | Poor devil, how could I be angry when I saw him lying in such a plight before me?

48 |

49 | “It's for your own sake, Watson,” he croaked.

50 |

51 | “For my sake?”

52 |

53 | “I know what is the matter with me. It is a coolie disease from Sumatra—a thing that the Dutch know more about than we, though they have made little of it up to date. One thing only is certain. It is infallibly deadly, and it is horribly contagious.”

54 |

55 | He spoke now with a feverish energy, the long hands twitching and jerking as he motioned me away.

56 |

57 | “Contagious by touch, Watson—that's it, by touch. Keep your distance and all is well.”

58 |

59 | “Good heavens, Holmes! Do you suppose that such a consideration weighs with me of an instant? It would not affect me in the case of a stranger. Do you imagine it would prevent me from doing my duty to so old a friend?”

60 |

61 | Again I advanced, but he repulsed me with a look of furious anger.

62 |

63 | “If you will stand there I will talk. If you do not you must leave the room.”

64 |

65 | I have so deep a respect for the extraordinary qualities of Holmes that I have always deferred to his wishes, even when I least understood them. But now all my professional instincts were aroused. Let him be my master elsewhere, I at least was his in a sick room.

66 |

67 | “Holmes,” said I, “you are not yourself. A sick man is but a child, and so I will treat you. Whether you like it or not, I will examine your symptoms and treat you for them.”

68 |

69 | He looked at me with venomous eyes.

70 |

71 | “If I am to have a doctor whether I will or not, let me at least have someone in whom I have confidence,” said he.

72 |

73 | “Then you have none in me?”

74 |

75 | “In your friendship, certainly. But facts are facts, Watson, and, after all, you are only a general practitioner with very limited experience and mediocre qualifications. It is painful to have to say these things, but you leave me no choice.”

76 |

77 | I was bitterly hurt.

78 |

79 | “Such a remark is unworthy of you, Holmes. It shows me very clearly the state of your own nerves. But if you have no confidence in me I would not intrude my services. Let me bring Sir Jasper Meek or Penrose Fisher, or any of the best men in London. But someone you must have, and that is final. If you think that I am going to stand here and see you die without either helping you myself or bringing anyone else to help you, then you have mistaken your man.”

80 |

81 | “You mean well, Watson,” said the sick man with something between a sob and a groan. “Shall I demonstrate your own ignorance? What do you know, pray, of Tapanuli fever? What do you know of the black Formosa corruption?”

82 |

83 | “I have never heard of either.”

84 |

85 | “There are many problems of disease, many strange pathological possibilities, in the East, Watson.” He paused after each sentence to collect his failing strength. “I have learned so much during some recent researches which have a medico-criminal aspect. It was in the course of them that I contracted this complaint. You can do nothing.”

86 |

87 | “Possibly not. But I happen to know that Dr. Ainstree, the greatest living authority upon tropical disease, is now in London. All remonstrance is useless, Holmes, I am going this instant to fetch him.” I turned resolutely to the door.

88 |

89 | Never have I had such a shock! In an instant, with a tiger-spring, the dying man had intercepted me. I heard the sharp snap of a twisted key. The next moment he had staggered back to his bed, exhausted and panting after his one tremendous outflame of energy.

90 |

91 | “You won't take the key from be by force, Watson, I've got you, my friend. Here you are, and here you will stay until I will otherwise. But I'll humour you.” (All this in little gasps, with terrible struggles for breath between.) “You've only my own good at heart. Of course I know that very well. You shall have your way, but give me time to get my strength. Not now, Watson, not now. It's four o'clock. At six you can go.”

92 |

93 | “This is insanity, Holmes.”

94 |

95 | “Only two hours, Watson. I promise you will go at six. Are you content to wait?”

96 |

97 | “I seem to have no choice.”

98 |

99 | “None in the world, Watson. Thank you, I need no help in arranging the clothes. You will please keep your distance. Now, Watson, there is one other condition that I would make. You will seek help, not from the man you mention, but from the one that I choose.”

100 |

101 | “By all means.”

102 |

103 | “The first three sensible words that you have uttered since you entered this room, Watson. You will find some books over there. I am somewhat exhausted; I wonder how a battery feels when it pours electricity into a non-conductor? At six, Watson, we resume our conversation.”

104 |

105 | But it was destined to be resumed long before that hour, and in circumstances which gave me a shock hardly second to that caused by his spring to the door. I had stood for some minutes looking at the silent figure in the bed. His face was almost covered by the clothes and he appeared to be asleep. Then, unable to settle down to reading, I walked slowly round the room, examining the pictures of celebrated criminals with which every wall was adorned. Finally, in my aimless perambulation, I came to the mantelpiece. A litter of pipes, tobacco-pouches, syringes, penknives, revolver-cartridges, and other debris was scattered over it. In the midst of these was a small black and white ivory box with a sliding lid. It was a neat little thing, and I had stretched out my hand to examine it more closely when—

106 |

107 | It was a dreadful cry that he gave—a yell which might have been heard down the street. My skin went cold and my hair bristled at that horrible scream. As I turned I caught a glimpse of a convulsed face and frantic eyes. I stood paralyzed, with the little box in my hand.

108 |

109 | “Put it down! Down, this instant, Watson—this instant, I say!” His head sank back upon the pillow and he gave a deep sigh of relief as I replaced the box upon the mantelpiece. “I hate to have my things touched, Watson. You know that I hate it. You fidget me beyond endurance. You, a doctor—you are enough to drive a patient into an asylum. Sit down, man, and let me have my rest!”

110 |

111 | The incident left a most unpleasant impression upon my mind. The violent and causeless excitement, followed by this brutality of speech, so far removed from his usual suavity, showed me how deep was the disorganization of his mind. Of all ruins, that of a noble mind is the most deplorable. I sat in silent dejection until the stipulated time had passed. He seemed to have been watching the clock as well as I, for it was hardly six before he began to talk with the same feverish animation as before.

112 |

113 | “Now, Watson,” said he. “Have you any change in your pocket?”

114 |

115 | “Yes.”

116 |

117 | “Any silver?”

118 |

119 | “A good deal.”

120 |

121 | “How many half-crowns?”

122 |

123 | “I have five.”

124 |

125 | “Ah, too few! Too few! How very unfortunate, Watson! However, such as they are you can put them in your watchpocket. And all the rest of your money in your left trouser pocket. Thank you. It will balance you so much better like that.”

126 |

127 | This was raving insanity. He shuddered, and again made a sound between a cough and a sob.

128 |

129 | “You will now light the gas, Watson, but you will be very careful that not for one instant shall it be more than half on. I implore you to be careful, Watson. Thank you, that is excellent. No, you need not draw the blind. Now you will have the kindness to place some letters and papers upon this table within my reach. Thank you. Now some of that litter from the mantelpiece. Excellent, Watson! There is a sugar-tongs there. Kindly raise that small ivory box with its assistance. Place it here among the papers. Good! You can now go and fetch Mr. Culverton Smith, of 13 Lower Burke Street.”

130 |

131 | To tell the truth, my desire to fetch a doctor had somewhat weakened, for poor Holmes was so obviously delirious that it seemed dangerous to leave him. However, he was as eager now to consult the person named as he had been obstinate in refusing.

132 |

133 | “I never heard the name,” said I.

134 |

135 | “Possibly not, my good Watson. It may surprise you to know that the man upon earth who is best versed in this disease is not a medical man, but a planter. Mr. Culverton Smith is a well-known resident of Sumatra, now visiting London. An outbreak of the disease upon his plantation, which was distant from medical aid, caused him to study it himself, with some rather far-reaching consequences. He is a very methodical person, and I did not desire you to start before six, because I was well aware that you would not find him in his study. If you could persuade him to come here and give us the benefit of his unique experience of this disease, the investigation of which has been his dearest hobby, I cannot doubt that he could help me.”

136 |

137 | I gave Holmes's remarks as a consecutive whole and will not attempt to indicate how they were interrupted by gaspings for breath and those clutchings of his hands which indicated the pain from which he was suffering. His appearance had changed for the worse during the few hours that I had been with him. Those hectic spots were more pronounced, the eyes shone more brightly out of darker hollows, and a cold sweat glimmered upon his brow. He still retained, however, the jaunty gallantry of his speech. To the last gasp he would always be the master.

138 |

139 | “You will tell him exactly how you have left me,” said he. “You will convey the very impression which is in your own mind—a dying man—a dying and delirious man. Indeed, I cannot think why the whole bed of the ocean is not one solid mass of oysters, so prolific the creatures seem. Ah, I am wondering! Strange how the brain controls the brain! What was I saying, Watson?”

140 |

141 | “My directions for Mr. Culverton Smith.”

142 |

143 | “Ah, yes, I remember. My life depends upon it. Plead with him, Watson. There is no good feeling between us. His nephew, Watson—I had suspicions of foul play and I allowed him to see it. The boy died horribly. He has a grudge against me. You will soften him, Watson. Beg him, pray him, get him here by any means. He can save me—only he!”

144 |

145 | “I will bring him in a cab, if I have to carry him down to it.”

146 |

147 | “You will do nothing of the sort. You will persuade him to come. And then you will return in front of him. Make any excuse so as not to come with him. Don't forget, Watson. You won't fail me. You never did fail me. No doubt there are natural enemies which limit the increase of the creatures. You and I, Watson, we have done our part. Shall the world, then, be overrun by oysters? No, no; horrible! You'll convey all that is in your mind.”

148 |

149 | I left him full of the image of this magnificent intellect babbling like a foolish child. He had handed me the key, and with a happy thought I took it with me lest he should lock himself in. Mrs. Hudson was waiting, trembling and weeping, in the passage. Behind me as I passed from the flat I heard Holmes's high, thin voice in some delirious chant. Below, as I stood whistling for a cab, a man came on me through the fog.

150 |

151 | “How is Mr. Holmes, sir?” he asked.

152 |

153 | It was an old acquaintance, Inspector Morton, of Scotland Yard, dressed in unofficial tweeds.

154 |

155 | “He is very ill,” I answered.

156 |

157 | He looked at me in a most singular fashion. Had it not been too fiendish, I could have imagined that the gleam of the fanlight showed exultation in his face.

158 |

159 | “I heard some rumour of it,” said he.

160 |

161 | The cab had driven up, and I left him.

162 |

163 | Lower Burke Street proved to be a line of fine houses lying in the vague borderland between Notting Hill and Kensington. The particular one at which my cabman pulled up had an air of smug and demure respectability in its old-fashioned iron railings, its massive folding-door, and its shining brasswork. All was in keeping with a solemn butler who appeared framed in the pink radiance of a tinted electrical light behind him.

164 |

165 | “Yes, Mr. Culverton Smith is in. Dr. Watson! Very good, sir, I will take up your card.”

166 |

167 | My humble name and title did not appear to impress Mr. Culverton Smith. Through the half-open door I heard a high, petulant, penetrating voice.

168 |

169 | “Who is this person? What does he want? Dear me, Staples, how often have I said that I am not to be disturbed in my hours of study?”

170 |

171 | There came a gentle flow of soothing explanation from the butler.

172 |

173 | “Well, I won't see him, Staples. I can't have my work interrupted like this. I am not at home. Say so. Tell him to come in the morning if he really must see me.”

174 |

175 | Again the gentle murmur.

176 |

177 | “Well, well, give him that message. He can come in the morning, or he can stay away. My work must not be hindered.”

178 |

179 | I thought of Holmes tossing upon his bed of sickness and counting the minutes, perhaps, until I could bring help to him. It was not a time to stand upon ceremony. His life depended upon my promptness. Before the apologetic butler had delivered his message I had pushed past him and was in the room.

180 |

181 | With a shrill cry of anger a man rose from a reclining chair beside the fire. I saw a great yellow face, coarse-grained and greasy, with heavy, double-chin, and two sullen, menacing gray eyes which glared at me from under tufted and sandy brows. A high bald head had a small velvet smoking-cap poised coquettishly upon one side of its pink curve. The skull was of enormous capacity, and yet as I looked down I saw to my amazement that the figure of the man was small and frail, twisted in the shoulders and back like one who has suffered from rickets in his childhood.

182 |

183 | “What's this?” he cried in a high, screaming voice. “What is the meaning of this intrusion? Didn't I send you word that I would see you to-morrow morning?”

184 |

185 | “I am sorry,” said I, “but the matter cannot be delayed. Mr. Sherlock Holmes—”

186 |

187 | The mention of my friend's name had an extraordinary effect upon the little man. The look of anger passed in an instant from his face. His features became tense and alert.

188 |

189 | “Have you come from Holmes?” he asked.

190 |

191 | “I have just left him.”

192 |

193 | “What about Holmes? How is he?”

194 |

195 | “He is desperately ill. That is why I have come.”

196 |

197 | The man motioned me to a chair, and turned to resume his own. As he did so I caught a glimpse of his face in the mirror over the mantelpiece. I could have sworn that it was set in a malicious and abominable smile. Yet I persuaded myself that it must have been some nervous contraction which I had surprised, for he turned to me an instant later with genuine concern upon his features.

198 |

199 | “I am sorry to hear this,” said he. “I only know Mr. Holmes through some business dealings which we have had, but I have every respect for his talents and his character. He is an amateur of crime, as I am of disease. For him the villain, for me the microbe. There are my prisons,” he continued, pointing to a row of bottles and jars which stood upon a side table. "Among those gelatine cultivations some of the very worst offenders in the world are now doing time."

200 |

201 | “It was on account of your special knowledge that Mr. Holmes desired to see you. He has a high opinion of you and thought that you were the one man in London who could help him.”

202 |

203 | The little man started, and the jaunty smoking-cap slid to the floor.

204 |

205 | “Why?” he asked. “Why should Mr. Homes think that I could help him in his trouble?”

206 |

207 | “Because of your knowledge of Eastern diseases.”

208 |

209 | “But why should he think that this disease which he has contracted is Eastern?”

210 |

211 | “Because, in some professional inquiry, he has been working among Chinese sailors down in the docks.”

212 |

213 | Mr. Culverton Smith smiled pleasantly and picked up his smoking-cap.

214 |

215 | “Oh, that's it—is it?” said he. “I trust the matter is not so grave as you suppose. How long has he been ill?”

216 |

217 | “About three days.”

218 |

219 | “Is he delirious?”

220 |

221 | “Occasionally.”

222 |

223 | “Tut, tut! This sounds serious. It would be inhuman not to answer his call. I very much resent any interruption to my work, Dr. Watson, but this case is certainly exceptional. I will come with you at once.”

224 |

225 | I remembered Holmes's injunction.

226 |

227 | “I have another appointment,” said I.

228 |

229 | “Very good. I will go alone. I have a note of Mr. Holmes's address. You can rely upon my being there within half an hour at most.”

230 |

231 | It was with a sinking heart that I reentered Holmes's bedroom. For all that I knew the worst might have happened in my absence. To my enormous relief, he had improved greatly in the interval. His appearance was as ghastly as ever, but all trace of delirium had left him and he spoke in a feeble voice, it is true, but with even more than his usual crispness and lucidity.

232 |

233 | “Well, did you see him, Watson?”

234 |

235 | “Yes; he is coming.”

236 |

237 | “Admirable, Watson! Admirable! You are the best of messengers.”

238 |

239 | “He wished to return with me.”

240 |

241 | “That would never do, Watson. That would be obviously impossible. Did he ask what ailed me?”

242 |

243 | “I told him about the Chinese in the East End.”

244 |

245 | “Exactly! Well, Watson, you have done all that a good friend could. You can now disappear from the scene.”

246 |

247 | “I must wait and hear his opinion, Holmes.”

248 |

249 | “Of course you must. But I have reasons to suppose that this opinion would be very much more frank and valuable if he imagines that we are alone. There is just room behind the head of my bed, Watson.”

250 |

251 | “My dear Holmes!”

252 |

253 | “I fear there is no alternative, Watson. The room does not lend itself to concealment, which is as well, as it is the less likely to arouse suspicion. But just there, Watson, I fancy that it could be done.” Suddenly he sat up with a rigid intentness upon his haggard face. “There are the wheels, Watson. Quick, man, if you love me! And don't budge, whatever happens—whatever happens, do you hear? Don't speak! Don't move! Just listen with all your ears.” Then in an instant his sudden access of strength departed, and his masterful, purposeful talk droned away into the low, vague murmurings of a semi-delirious man.

254 |

255 | From the hiding-place into which I had been so swiftly hustled I heard the footfalls upon the stair, with the opening and the closing of the bedroom door. Then, to my surprise, there came a long silence, broken only by the heavy breathings and gaspings of the sick man. I could imagine that our visitor was standing by the bedside and looking down at the sufferer. At last that strange hush was broken.

256 |

257 | “Holmes!” he cried. “Holmes!” in the insistent tone of one who awakens a sleeper. "Can't you hear me, Holmes?" There was a rustling, as if he had shaken the sick man roughly by the shoulder.

258 |

259 | “Is that you, Mr. Smith?” Holmes whispered. “I hardly dared hope that you would come.”

260 |

261 | The other laughed.