├── deploy_key.enc

├── book.json

├── GLOSSARY.md

├── chapter_1

├── lecture_14.md

├── lecture_3.md

├── lecture_4.md

├── lecture_7.md

├── lecture_5.md

├── lecture_6.md

├── lecture_10.md

├── lecture_12.md

├── lecture_11.md

├── lecture_2.md

├── lecture_8.md

├── lecture_13.md

├── lecture_9.md

└── lecture_1.md

├── LICENSE.md

├── .travis.yml

├── .gitignore

├── deploy.sh

├── SUMMARY.md

└── README.md

/deploy_key.enc:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rabuf/applied-category-theory/HEAD/deploy_key.enc

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/book.json:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | {

2 | "plugins": ["mathjax"],

3 | "title" : "Applied Category Theory",

4 | "author" : "John Baez"

5 | }

6 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/GLOSSARY.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ## Term

2 | Definition for this term

3 |

4 | ## Another term

5 | With it's definition, this can contain bold text

6 | and all other kinds of inline markup ...

7 |

8 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_14.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 14 - Adjoints, Joints, and Meets

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

5 |

6 | [Click here to read the original discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/2013/lecture-14-chapter-1-adjoints-joins-and-meets/p1)

7 |

8 | ---

9 |

10 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

11 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/LICENSE.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ## License

2 |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

3 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/.travis.yml:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | language: node_js

2 | node_js:

3 | - stable

4 | install:

5 | - npm install gitbook-cli -g

6 | script:

7 | - bash deploy.sh

8 | env:

9 | global:

10 | - KEY_FILE="deploy_key"

11 | - GIT_EMAIL="jtsummers@gmail.com"

12 | before_install:

13 | - openssl aes-256-cbc -K $encrypted_50a456097cc2_key -iv $encrypted_50a456097cc2_iv

14 | -in deploy_key.enc -out deploy_key -d

15 | cache:

16 | directories:

17 | - "node_modules"

18 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/.gitignore:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Node rules:

2 | ## Grunt intermediate storage (http://gruntjs.com/creating-plugins#storing-task-files)

3 | .grunt

4 |

5 | ## Dependency directory

6 | ## Commenting this out is preferred by some people, see

7 | ## https://docs.npmjs.com/misc/faq#should-i-check-my-node_modules-folder-into-git

8 | node_modules

9 |

10 | # Book build output

11 | _book

12 |

13 | # eBook build output

14 | *.epub

15 | *.mobi

16 | *.pdf

17 | *\~

18 |

19 | # For travis deployment

20 | deploy_key

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/deploy.sh:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | #!/bin/bash

2 |

3 | pwd

4 | git config remote.origin.url

5 | rev=$(git rev-parse --short HEAD)

6 |

7 | REPO=`git config remote.origin.url`

8 | SSH_REPO=${REPO/https:\/\/github.com\//git@github.com:}

9 |

10 | chmod 600 deploy_key

11 | eval `ssh-agent -s`

12 | ssh-add $KEY_FILE

13 |

14 | gitbook install && gitbook build

15 | cd _book

16 | git init

17 | git remote add upstream $SSH_REPO

18 | git fetch upstream && git reset upstream/gh-pages

19 | git checkout gh-pages

20 | rm .travis.yml deploy.sh deploy_key.enc

21 | git add .

22 | git commit -m "Rebuild pages at ${rev}"

23 | git push upstream gh-pages

24 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/SUMMARY.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Summary

2 |

3 | * [Introduction](README.md)

4 |

5 | ### Chapter 1

6 |

7 | * [Lecture 1 - Introduction](chapter_1/lecture_1.md)

8 | * [Lecture 2 - What is Applied Category Theory?](chapter_1/lecture_2.md)

9 | * [Lecture 3 - Posets](chapter_1/lecture_3.md)

10 | * [Lecture 4 - Galois Connections Part 1](chapter_1/lecture_4.md)

11 | * [Lecture 5 - Galois Connections Part 2](chapter_1/lecture_5.md)

12 | * [Lecture 6 - Computing Adjoints](chapter_1/lecture_6.md)

13 | * [Lecture 7 - Logic](chapter_1/lecture_7.md)

14 | * [Lecture 8 - The Logic of Subsets](chapter_1/lecture_8.md)

15 | * [Lecture 9 - Adjoints and the Logic of Subsets](chapter_1/lecture_9.md)

16 | * [Lecture 10 - The Logic of Partitions](chapter_1/lecture_10.md)

17 | * [Lecture 11 - The Poset of Partitions](chapter_1/lecture_11.md)

18 | * [Lecture 12 - Generative Effects](chapter_1/lecture_12.md)

19 | * [Lecture 13 - Pulling Back Partitions](chapter_1/lecture_13.md)

20 | * [Lecture 14 - Adjoints, Joins, and Meets](chapter_1/lecture_14.md)

21 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/README.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Introduction

2 | Hi! Welcome to the *GitBook-version of the* **[Applied Category Theory Course](https://johncarlosbaez.wordpress.com/2018/03/26/seven-sketches-in-compositionality/)**. The full course exists on the [Azimuth Forum](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/categories/applied-category-theory-course) and this is a collection of the lectures that John Baez posted in the forum, in a GitBook-format.

3 |

4 | To begin, you can download a copy of the text:

5 |

6 | * Brendan Fong and David Spivak, _[Seven Sketches in Compositionality: An Invitation to Applied Category Theory](http://math.mit.edu/~dspivak/teaching/sp18/7Sketches.pdf)_.

7 |

8 | Then start reading the lectures.

9 |

10 | If you want to actively participate in the course, you can start with

11 | [John Baez's welcome

12 | message](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1717/welcome-to-the-applied-category-theory-course/p1). There

13 | you'll find information on registering with the forum and

14 | participating in the discussion.

15 |

16 | If you think you've found a mistake in the book, please report it

17 | here:

18 |

19 | * [Seven Sketches book: Typos, comments, questions, and suggestions.](https://docs.google.com/document/d/160G9OFcP5DWT8Stn7TxdVx83DJnnf7d5GML0_FOD5Wg/edit)

20 |

21 | If it's really a mistake, Fong and Spivak will fix it!

22 |

23 | ---

24 |

25 | - The source for this book can be found [here](https://github.com/rabuf/applied-category-theory).

26 |

27 | - The online book can be found [here](https://rabuf.github.io/applied-category-theory/).

28 |

29 | ---

30 | {% include "./LICENSE.md" %}

31 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_3.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 3 - Posets

2 | ---------

3 |

4 | Okay, let's get started!

5 |

6 | Fong and Spivak start out by explaining **posets**, which is short for

7 | "partially ordered sets". Whenever you have a set of things and a

8 | reasonable way deciding when anything in that set is "bigger" than

9 | some other thing, or "more expensive", or "taller", or "heavier", or

10 | "better" in any well-defined sense, or... anything like that, you've

11 | got a poset. When \\(y\\) is bigger than \\(x\\) we write \\(x \le

12 | y\\). (You can also write \\(y \ge x\\), of course.)

13 |

14 | What do I mean by "reasonable"? We demand that the \\(\le\\) relation

15 | obey these rules:

16 |

17 | 1. **reflexivity**: \\(x \le x\\)

18 |

19 | 2. **transitivity** \\(x \le y\\) and \\(y \le z\\) imply \\(x \le

20 | z\\).

21 |

22 | A set with a relation obeying these rules is called a

23 | **[preorder](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preorder)**.

24 |

25 | This is a fundamental concept! After all, humans are always busy

26 | trying to compare things and see what's better. So, we'll start by

27 | studying preorders.

28 |

29 | But I can't resist revealing a secret trick that Fong and Spivak are

30 | playing on you here. Why in the world should a book on applied

31 | category theory start by discussing preorders? Why not start by

32 | discussing _categories?_

33 |

34 | The answer: a preorder is an especially simple kind of category. A

35 | category, as you may have heard, has a bunch of 'objects'

36 | \\(x,y,z,\dots\\) and 'morphisms' between them. A morphism from

37 | \\(x\\) to \\(y\\) is written \\(f : x \to y\\). You can 'compose' a

38 | morphism from \\(f : x \to y\\) with a morphism from \\(g: y \to z\\)

39 | and get a morphism \\(gf : x \to z\\). Every object \\(x\\) has an

40 | 'identity' morphism \\(1_x : x \to x\\). And a few simple rules must

41 | hold. We'll get into them later.

42 |

43 | But a category with _at most one_ morphism from any object \\(x\\) to

44 | any object \\(y\\) is really just a preorder! If there's a morphism

45 | from \\(x\\) to \\(y\\) we simply write \\(x \le y\\). We don't need

46 | to give the morphism a name because there's at most one from \\(x\\)

47 | to \\(y\\).

48 |

49 | So, the study of preorders is a baby version of category theory, where

50 | everything gets much easier! And when Fong and Spivak are teaching

51 | you about preorders, they're sneakily getting you used to categories.

52 | Then, when they introduce categories explicitly, you can always fall

53 | back on preorders as examples.

54 |

55 | I've posted 4 puzzles on preorders

56 | [here](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/comment/15878/#Comment_15878).

57 | Look at them! I just answered Puzzle 3. Puzzle 4 has millions of

58 | answers - come up with another! Also look at Puzzle 5

59 | [here](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/comment/15954/#Comment_15954).

60 | And people who already know the definition of a category, and want to

61 | ponder how preorders are a special case of categories, should try

62 | Puzzles 6 and 7

63 | [here](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/comment/16077/#Comment_16077).

64 |

65 | ---

66 |

67 | [Click here to read the original

68 | discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1812/lecture-3-chapter-1-posets/p1)

69 |

70 | ---

71 |

72 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

73 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_4.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 4 - Galois Connections Part 1

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

5 | Okay, now let's get to the cool part: Galois connections. Before he

6 | died in a duel, the young [Évariste

7 | Galois](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89variste_Galois) proved

8 | that you couldn't solve the quintic equation with radicals: that is,

9 | there's nothing like the quadratic formula for equations like:

10 |

11 | \\[ax^5 + bx^4 + cx^3 + dx^2 + ex + f = 0.\\]

12 |

13 | He used a trick for converting one view of a problem into another, and

14 | then converting the other view back into the original one. And by now,

15 | we've extracted the essence of this trick and dubbed it a "Galois

16 | connection". It's far more general than Galois dreamed. More

17 | [here.](https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/de4c/0a1a2269ddee82bd2d21f1ae23cdadb09cd7.pdf)

18 |

19 | Remember, a **[preorder](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preorder)** is

20 | a set \\(A\\) with a relation \\(\le_A\\) that's reflexive and

21 | transitive. When we're in the mood for being careful, we write a

22 | preorder as a pair \\( (A,\le_A)\\). When we're feeling lazy we'll

23 | just call it something like \\(A\\), and just write \\(\le\\) for the

24 | relation.

25 |

26 | **Definition.** Given preorders \\((A,\le_A)\\) and \\((B,\le_B)\\), a

27 | **monotone map** from \\(A\\) to \\(B\\) is a function \\(f : A \to

28 | B\\) such that

29 |

30 | \\[x \le_A y \textrm{ implies } f(x) \le_B f(y).\\]

31 |

32 | for all elements \\(x,y \in A\\),

33 |

34 | **Puzzle 10.** There are many examples of monotone maps between

35 | posets. List a few interesting ones!

36 |

37 | **Definition.** Given preorders \\((A,\le_A)\\) and \\((B,\le_B)\\), a

38 | **[Galois

39 | connection](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galois_connection)** is a

40 | monotone map \\(f : A \to B\\) together with a monotone map \\(g: B

41 | \to A\\) such that

42 |

43 | \\[f(a) \le_B b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le_A g(b)\\]

44 |

45 | for all \\(a \in A, b \in B\\). In this situation we call \\(f\\) the

46 | **left adjoint** and \\(g\\) the **right adjoint**.

47 |

48 | So, the right adjoint of \\(f\\) is a way of going back from \\(B\\)

49 | to \\(A\\) that's related to \\(f\\) in some way.

50 |

51 | **Puzzle 11.** Show that if the monotone map \\(f: A \to B\\) has an

52 | inverse \\(g : B \to A \\) that is also a monotone map, then \\(g\\)

53 | is _both a right adjoint and a left adjoint_ of \\(f\\).

54 |

55 | So, adjoints are some sort of generalization of inverses. But as

56 | you'll eventually see, they're much more exciting!

57 |

58 | I will spend quite a few lectures describing really interesting

59 | examples, and you'll start seeing what Galois connections are good

60 | for. It shouldn't be obvious yet, unless you already happen to know or

61 | you're some sort of superhuman genius. I just want to get the

62 | definition on the table right away.

63 |

64 | Here's one easy example to get you started. Let \\(\mathbb{N}\\) be

65 | the set of natural numbers with its usual notion of \\(\le\\).

66 | There's a function \\(f : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) with \\(f(x) =

67 | 2x \\). This function doesn't have an inverse. But:

68 |

69 | **Puzzle 12.** Find a right adjoint for \\(f\\): that is, a function

70 | \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) with

71 |

72 | \\[f(m) \le n \textrm{ if and only if } m \le g(n)\\]

73 |

74 | for all \\(m,n \in \mathbb{N}\\). How many right adjoints can you

75 | find?

76 |

77 | **Puzzle 13.** Find a left adjoint for \\(f\\): that is, a function

78 | \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) with

79 |

80 | \\[g(m) \le n \textrm{ if and only if } m \le f(n)\\]

81 |

82 | for all \\(m,n \in \mathbb{N}\\). How many left adjoints can you find?

83 |

84 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

85 |

86 | ---

87 |

88 | [Click here to read the original

89 | discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1828/lecture-4-chapter-1-galois-connections/p1)

90 |

91 | ---

92 |

93 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

94 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_7.md:

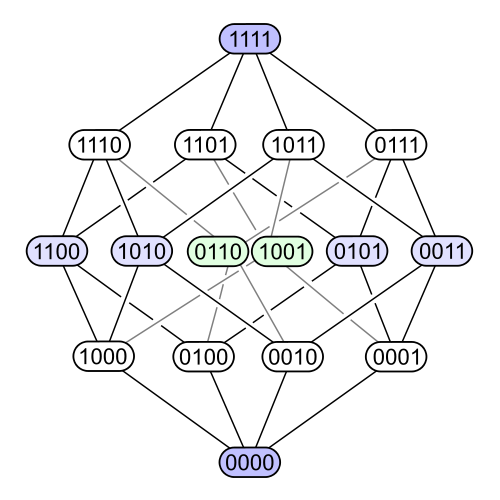

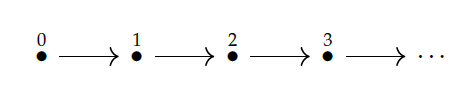

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 7 - Logic

2 | ---

3 |

4 | So far the only _examples_ of posets I've talked about in the lectures

5 | are the real numbers \\(\mathbb{R}\\) and the natural numbers

6 | \\(\mathbb{N}\\) with their usual order \\(\le\\). Of course every

7 | natural number is a real number, so there's a function

8 |

9 | \\[i : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{R}\\]

10 |

11 | sending any natural number \\(x \in \mathbb{N}\\) to the exact same

12 | number regarded as a real number. This function is monotone, so you

13 | now know instinctively to ask this question:

14 |

15 | **Puzzle 21.** Does the monotone function \\(i : \mathbb{N} \to

16 | \mathbb{R}\\) have a left adjoint? Does it have a right adjoint? If

17 | so, what are they?

18 |

19 | This is nice, but we need to look at other examples to appreciate the

20 | diversity of posets. Both \\(\mathbb{N}\\) and \\(\mathbb{Z}\\) have a

21 | very special property. They are **[totally ordered

22 | sets](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Total_order)**: posets such that

23 |

24 | \\[\textrm{ for all } x, y, \textrm{ either } x \le y \textrm{ or } y \le x .\\]

25 |

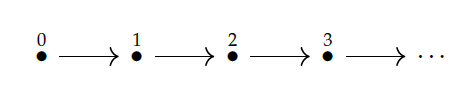

26 | If you want to show off, you can call totally ordered sets **tosets**.

27 | They're also called **linearly ordered**, because you can imagine them

28 | as lines:

29 |

30 |  31 |

32 | Totally ordered sets are limiting. Suppose you're trying to order

33 | foods on a restaurant menu based on how much you like them. What's

34 | better: a cheese sandwich or a pancake? There may be no answer,

35 | because you like them in _different ways_. To get a totally ordered

36 | set you have to ignore this and arrange all the foods in a line.

37 |

38 | In standard economics we _do_ try to arrange everything in a line. We

39 | measure the worth of everything in real numbers: numbers of _dollars_.

40 | There's even a theorem to justify this, proved by [von Neumann and

41 | Morgenstern](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Von_Neumann%E2%80%93Morgenstern_utility_theorem).

42 | But the assumptions of this theorem don't hold in real life. It's

43 | mainly just _convenient_ to measure value, or "utility", in real

44 | numbers. With computer technologies we could set up cryptocurrencies

45 | based on other posets. But will we?

46 |

47 | Luckily, human thought as a whole is not limited to total orders. A

48 | good example is logic. Logic, in its simplest form, is about

49 | statements \\(P, Q, R, \dots \\) and whether one statement implies

50 | another. If \\(P\\) implies \\(Q\\) we often write \\(P \implies

51 | Q\\). There are many kinds of logic, but every kind I know, this

52 | relation \\(\implies\\) makes statements into a preorder, since we

53 | have

54 |

55 | 1) reflexivity: \\(P \implies P\\)

56 |

57 | 2) transitivity: if \\(P \implies Q\\) and \\( Q \implies R \\) then

58 | \\(P \implies R\\).

59 |

60 | Often people make this preorder into a poset by imposing this rule:

61 |

62 | 3) antisymmetry: if \\(P \implies Q\\) and \\(Q \implies P\\) then

63 | \\(P = Q\\).

64 |

65 | This amounts to decreeing that we count two statements as "the same"

66 | if they both imply each other. We may not always want to do this.

67 | And we certainly don't want a linear order: it's easy to find examples

68 | of statements such that neither \\(P \implies Q\\) nor \\(Q \implies

69 | P\\), like "I am a millionaire" and "I am happy", or "I like this food

70 | for breakfast" and "I like this food for lunch".

71 |

72 | So, to continue our study of preorders, posets, monotone functions and

73 | Galois connections, we'll turn to logic! Category-theoretic logic is

74 | an enormous wonderful field, but we'll just do a bit of logic based on

75 | the poset of subsets of a set, followed by a bit of logic based on the

76 | poset of partitions of a set. The latter underlies Fong and Spivak's

77 | discussion of "generative effects" in Chapter 1.

78 |

79 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

80 |

81 | ---

82 |

83 | [Click here to read the original discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1909/lecture-7-chapter-1-logic/p1)

84 |

85 | ---

86 |

87 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

88 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_5.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 5 - Galois Connections Part 2

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

5 | Okay: I've told you what a Galois connection is. But now it's time to

6 | explain why they matter. This will take much longer - and be much more

7 | fun.

8 |

9 | Galois connections do something really cool: they tell you _the best

10 | possible way to recover data that can't be recovered_.

11 |

12 | More precisely, they tell you _the best approximation to reversing a

13 | computation that can't be reversed._

14 |

15 | Someone hands you the output of some computation, and asks you what

16 | the input was. Sometimes there's a unique right answer. But sometimes

17 | there's more than one answer, or none! That's when your job gets

18 | hard. In fact, impossible! But don't let that stop you.

19 |

20 |

31 |

32 | Totally ordered sets are limiting. Suppose you're trying to order

33 | foods on a restaurant menu based on how much you like them. What's

34 | better: a cheese sandwich or a pancake? There may be no answer,

35 | because you like them in _different ways_. To get a totally ordered

36 | set you have to ignore this and arrange all the foods in a line.

37 |

38 | In standard economics we _do_ try to arrange everything in a line. We

39 | measure the worth of everything in real numbers: numbers of _dollars_.

40 | There's even a theorem to justify this, proved by [von Neumann and

41 | Morgenstern](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Von_Neumann%E2%80%93Morgenstern_utility_theorem).

42 | But the assumptions of this theorem don't hold in real life. It's

43 | mainly just _convenient_ to measure value, or "utility", in real

44 | numbers. With computer technologies we could set up cryptocurrencies

45 | based on other posets. But will we?

46 |

47 | Luckily, human thought as a whole is not limited to total orders. A

48 | good example is logic. Logic, in its simplest form, is about

49 | statements \\(P, Q, R, \dots \\) and whether one statement implies

50 | another. If \\(P\\) implies \\(Q\\) we often write \\(P \implies

51 | Q\\). There are many kinds of logic, but every kind I know, this

52 | relation \\(\implies\\) makes statements into a preorder, since we

53 | have

54 |

55 | 1) reflexivity: \\(P \implies P\\)

56 |

57 | 2) transitivity: if \\(P \implies Q\\) and \\( Q \implies R \\) then

58 | \\(P \implies R\\).

59 |

60 | Often people make this preorder into a poset by imposing this rule:

61 |

62 | 3) antisymmetry: if \\(P \implies Q\\) and \\(Q \implies P\\) then

63 | \\(P = Q\\).

64 |

65 | This amounts to decreeing that we count two statements as "the same"

66 | if they both imply each other. We may not always want to do this.

67 | And we certainly don't want a linear order: it's easy to find examples

68 | of statements such that neither \\(P \implies Q\\) nor \\(Q \implies

69 | P\\), like "I am a millionaire" and "I am happy", or "I like this food

70 | for breakfast" and "I like this food for lunch".

71 |

72 | So, to continue our study of preorders, posets, monotone functions and

73 | Galois connections, we'll turn to logic! Category-theoretic logic is

74 | an enormous wonderful field, but we'll just do a bit of logic based on

75 | the poset of subsets of a set, followed by a bit of logic based on the

76 | poset of partitions of a set. The latter underlies Fong and Spivak's

77 | discussion of "generative effects" in Chapter 1.

78 |

79 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

80 |

81 | ---

82 |

83 | [Click here to read the original discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1909/lecture-7-chapter-1-logic/p1)

84 |

85 | ---

86 |

87 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

88 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_5.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 5 - Galois Connections Part 2

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

5 | Okay: I've told you what a Galois connection is. But now it's time to

6 | explain why they matter. This will take much longer - and be much more

7 | fun.

8 |

9 | Galois connections do something really cool: they tell you _the best

10 | possible way to recover data that can't be recovered_.

11 |

12 | More precisely, they tell you _the best approximation to reversing a

13 | computation that can't be reversed._

14 |

15 | Someone hands you the output of some computation, and asks you what

16 | the input was. Sometimes there's a unique right answer. But sometimes

17 | there's more than one answer, or none! That's when your job gets

18 | hard. In fact, impossible! But don't let that stop you.

19 |

20 |  22 |

23 | Suppose we have a function between sets, \\(f : A \to B\\). We say a

24 | function \\(g: B \to A\\) is the **inverse** of \\(f\\) if

25 |

26 | \\[g(f(a)) = a \textrm{ for all } a \in A \quad \textrm{ and } \quad f(g(b)) = b \textrm{ for all } b \in B\\]

27 |

28 | Another equivalent way to say this is that

29 |

30 | \\[f(a) = b \textrm{ if and only if } a = g(b)\\]

31 |

32 | for all \\(a \in A\\) and \\(b \in B\\).

33 |

34 | So, the idea is that \\(g\\) undoes \\(f\\). For example, if \\(A = B

35 | = \mathbb{R}\\) is the set of real numbers, and \\(f\\) doubles every

36 | number, then \\(f\\) has an inverse \\(g\\), which halves every

37 | number.

38 |

39 | But what if \\(A = B = \mathbb{N}\\) is the set of _natural_ numbers,

40 | and \\(f\\) doubles every natural number. This function has no

41 | inverse!

42 |

43 | So, if I say "\\(2a = 4\\); tell me \\(a\\)" you can say \\(a = 2\\).

44 | But if I say "\\(2a = 3\\); tell me \\(a\\)" you're stuck.

45 |

46 | But you can still try to give me a "best approximation" to the

47 | nonexistent natural number \\(a\\) with \\(2 a = 3\\).

48 |

49 | "Best" in what sense? We could look for the number \\(a\\) that makes

50 | \\(2a\\) as close as possible to 3. There are two equally good

51 | options: \\(a = 1\\) and \\(a = 2\\). Here we are using the usual

52 | distance function, or

53 | [metric](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metric_(mathematics)), on

54 | \\(\mathbb{N}\\), which says that the distance between \\(x\\) and

55 | \\(y\\) is \\(|x-y|\\).

56 |

57 | But we're not talking about distance functions in this class now!

58 | We're talking about _preorders_. Can we define a "best approximation"

59 | using just the relation \\(\le\\) on \\(\mathbb{N}\\)?

60 |

61 | Yes! But we can do it in two ways!

62 |

63 | **Best approximation from below.** Find the largest possible \\(a \in

64 | \mathbb{N}\\) such that \\(2a \le 3\\). Answer: \\(a = 1\\).

65 |

66 | **Best approximation from above.** Find the smallest possible \\(a \in

67 | \mathbb{N}\\) such that \\(3 \le 2a\\). Answer: \\(a = 2\\).

68 |

69 | Okay, now work this out more generally:

70 |

71 | **Puzzle 14.** Find the function \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\)

72 | such that \\(g(b) \\) is the largest possible natural number \\(a\\)

73 | with \\(2a \le b\\).

74 |

75 | **Puzzle 15.** Find the function \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\)

76 | such that \\(g(b)\\) is the smallest possible natural number \\(a\\)

77 | with \\(b \le 2a\\).

78 |

79 | Now think about [Lecture 4](lecture_4.md) and the puzzles there! I'll

80 | copy them here with notation that better matches what I'm using now:

81 |

82 | **Puzzle 12.** Find a right adjoint for the function \\(f: \mathbb{N}

83 | \to \mathbb{N}\\) that doubles natural numbers: that is, a function

84 | \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) with

85 |

86 | \\[f(a) \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le g(b)\\]

87 |

88 | for all \\(a,b \in \mathbb{N}\\).

89 |

90 | **Puzzle 13.** Find a left adjoint for the same function \\(f\\): that

91 | is, a function \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) with

92 |

93 | \\[g(b) \le a \textrm{ if and only if } b \le f(a)\\]

94 |

95 | Next:

96 |

97 | **Puzzle 16.** What's going on here? What's the pattern you see, and

98 | why is it working this way?

99 |

100 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

101 |

102 | ---

103 |

104 | [Click here to read the original

105 | discussion](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1845/lecture-5-chapter-1-galois-connections/p1)

106 |

107 | ---

108 |

109 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

110 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_6.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 6 - Computing Adjoints

2 | ---

3 | I've already said that left and right adjoints give _the best

4 | approximate ways to solve a problem that has no solution_, namely

5 | finding the inverse of a monotone function that has no inverse. I've

6 | defined them and given you some puzzles about them. But now let's

7 | review these puzzles and extract some valuable lessons!

8 |

9 | We took the function \\(f : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) that doubles

10 | any natural number

11 |

12 | \\[f(a) = 2a .\\]

13 |

14 | This function has no inverse, since you can't divide an odd number by

15 | 2 and get a natural number! But if you did the puzzles, you saw that

16 | \\(f\\) has a "right adjoint" \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\).

17 | This is defined by the property

18 |

19 | \\[f(a) \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le g(b) .\\]

20 |

21 | or in other words,

22 |

23 | \\[2a \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le g(b) .\\]

24 |

25 | Using our knowledge of fractions, we have

26 |

27 | \\[2a \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le b/2\\]

28 |

29 | but since \\(a\\) is a natural number, this implies

30 |

31 | \\[2a \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le \lfloor b/2 \rfloor\\]

32 |

33 | where we are using the [floor

34 | function](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floor_and_ceiling_functions)

35 | to pick out the largest integer \\(\le b/2\\). So,

36 |

37 | \\[g(b) = \lfloor b/2 \rfloor.\\]

38 |

39 | Moral: the right adjoint \\(g\\) is the "best approximation from

40 | below" to the nonexistent inverse of \\(f\\).

41 |

42 | If you did the puzzles, you also saw that \\(f\\) has a left adjoint!

43 | This is the "best approximation from above" to the nonexistent inverse

44 | of \\(f\\): it gives you the smallest integer that's \\(\ge n/2\\).

45 |

46 | So, while \\(f\\) has no inverse, it has two "approximate inverses".

47 | The left adjoint comes as close as possible to the (perhaps

48 | nonexistent) correct answer while making sure to never choose a number

49 | that's _too small_. The right adjoint comes as close as possible while

50 | making sure to never choose a number that's _too big_.

51 |

52 | The two adjoints represent two opposing philosophies of life: _make

53 | sure you never ask for too little_ and _make sure you never ask for

54 | too much_. This is why they're philosophically profound. But the great

55 | thing is that they are defined in a completely precise, systematic way

56 | that applies to a huge number of situations!

57 |

58 | If you need a mnemonic to remember which is which, remember left

59 | adjoints are "left-wing" or "liberal" or "generous", while right

60 | adjoints are "right-wing" or "conservative" or "cautious".

61 |

62 | Let's think a bit more about how we can compute them in general,

63 | starting from the basic definition.

64 |

65 | Here's the definition again. Suppose we have two preorders

66 | \\((A,\le_A)\\) and \\((B,\le_B)\\) and a monotone function \\(f : A

67 | \to B\\). Then we say a monotone function \\(g: B \to A\\) is a

68 | **right adjoint of \\(f\\)** if

69 |

70 | \\[f(a) \le_B b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le_A g(b)\\]

71 |

72 | for all \\(a \in A\\) and \\(b \in B\\). In this situation we also say

73 | that \\(f\\) is a **left adjoint of \\(g\\)**.

74 |

75 | The names should be easy to remember, since \\(f\\) shows up on the

76 | _left_ of the inequality $$f(a) \le_B b$$, while \\(g\\) shows up on

77 | the _right_ of the inequality \\(a \le_A g(b)\\). But let's see how

78 | they actually work!

79 |

80 | Suppose you know \\(f : A \to B\\) and you're trying to figure out its

81 | right adjoint \\(g: B \to A\\). Say you're trying to figure out

82 | \\(g(b)\\). You don't know what it is, but you know

83 |

84 | \\[f(a) \le_B b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le_A g(b)\\]

85 |

86 | So, you go around looking at choices of \\(a \in A\\). For each one

87 | you compute \\(f(a)\\). If \\(f(a) \le_B b\\), then you know \\(a

88 | \le_A g(b)\\). So, you need to choose \\(g(b)\\) to be greater than or

89 | equal to every element of this set:

90 |

91 | \\[\{a \in A : \; f(a) \le_B b \}\\]

92 |

93 | In other words, \\(g(b)\\) must be an **[upper

94 | bound](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_and_lower_bounds)** of this

95 | set. But you shouldn't choose \\(g(b)\\) to be any bigger than it

96 | needs to be! After all, you know $$a \le_A g(b)$$ _only if_ $$f(a)

97 | \le_B b$$. So, \\(g(b)\\) must be a **[least upper

98 | bound](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infimum_and_supremum)** of the

99 | above set.

100 |

101 | Note that I'm carefully speaking about _a_ least upper bound. Our set

102 | could have two different least upper bounds, say \\(a\\) and \\(a'\\).

103 | Since they're both the least, we must have \\(a \le a'\\) and \\(a'

104 | \le a\\). This doesn't imply \\(a = a'\\), in general! But it does if

105 | our preorder \\(A\\) is a "poset". A **poset** is a preorder \\((A,

106 | \le_A)\\) obeying this extra axiom:

107 |

108 | \\[\textrm{ if } a \le a' \textrm{ and } a' \le a \textrm{ then } a = a'\\]

109 |

110 | for all \\(a,a' \in A\\).

111 |

112 | In a poset, our desired least upper bound may still not _exist_. But

113 | if it does, it's _unique_, and Fong and Spivak write it this way:

114 |

115 | \\[\bigvee \{a \in A : \; f(a) \le_B b \}\\]

116 |

117 | The \\(\bigvee\\) symbol stands for "least upper bound", also known as

118 | **supremum** or **join**.

119 |

120 | So, here's what we've shown:

121 |

122 | If \\(f : A \to B\\) has a right adjoint \\(g : B \to A\\) and \\(A\\)

123 | is a poset, this right adjoint is unique and we have a formula for it:

124 |

125 | \\[g(b) = \bigvee \{a \in A : \; f(a) \le_B b \} .\\]

126 |

127 | And we can copy our whole line of reasoning and show this:

128 |

129 | If \\(g : B \to A\\) has a left adjoint \\(f : A \to B\\) and \\(B\\)

130 | is a poset, this left adjoint is unique and we have a formula for it:

131 |

132 | \\[f(a) = \bigwedge \{b \in B : \; a \le_A g(b)\}.\\]

133 |

134 | Here the \\(\bigwedge\\) symbol stands for "greatest lower bound",

135 | also known as the **infimum** or **meet**.

136 |

137 | We're making progress: we can now actually compute left and right

138 | adjoints! Next we'll start looking at more examples.

139 |

140 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

141 |

142 | ---

143 |

144 | [Click here to read the original discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1901/lecture-6-chapter-1-computing-adjoints/p1)

145 |

146 | ---

147 |

148 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

149 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_10.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

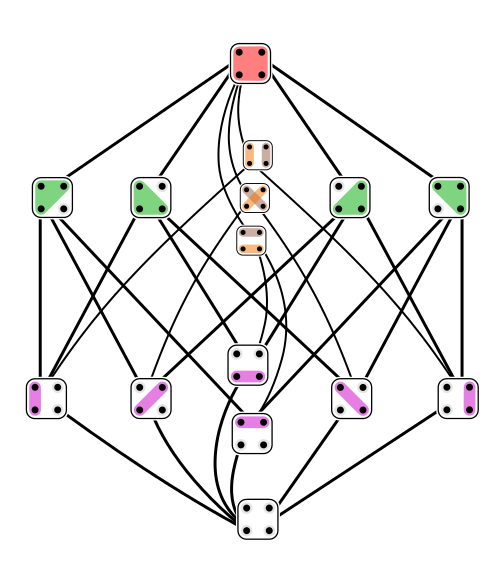

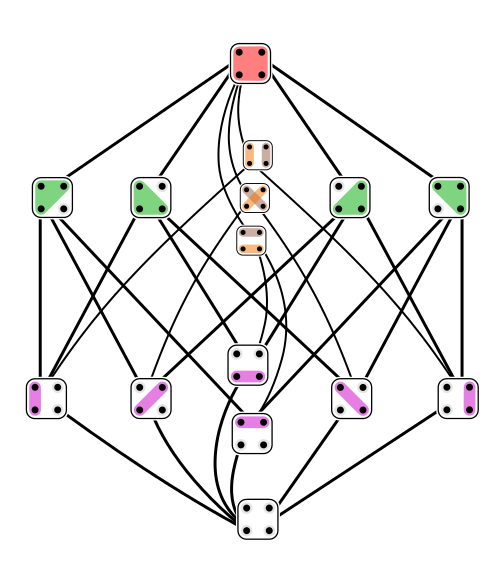

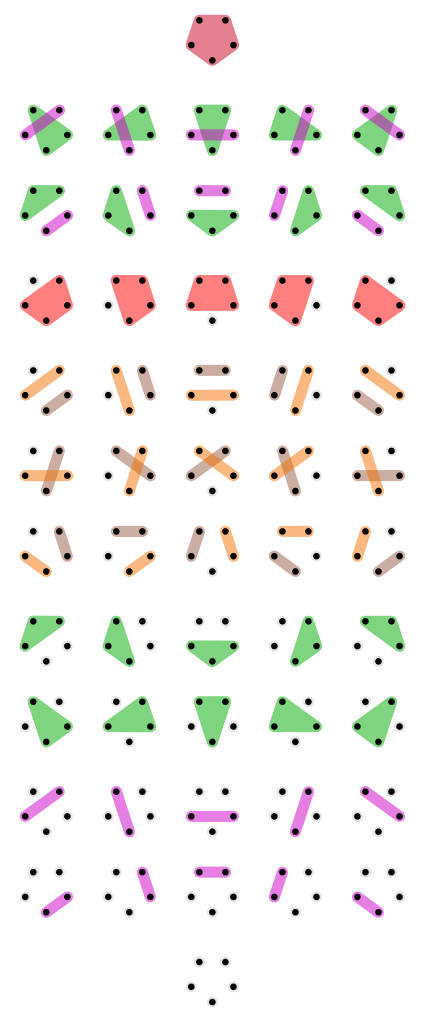

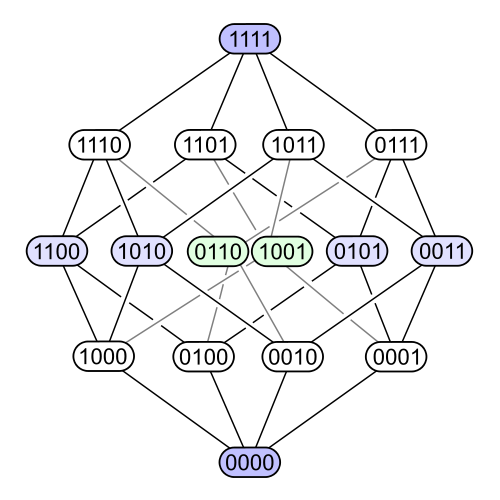

1 | # Lecture 10 - The Logic of Partitions

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

5 | I've been explaining how we can create a version of logic starting

6 | from any poset, which we think of as a poset of "propositions". There

7 | are various ways to get our hands on such a poset. One way is to start

8 | with a set \\(X\\) and build a poset \\(P(X)\\) whose elements are

9 | subsets of \\(X\\). This leads to the most traditional form of logic,

10 | called classical logic. But another way is to start with a set \\(X\\)

11 | and build a poset \\(\mathcal{E}(X)\\) whose elements are "partitions"

12 | of \\(X\\). This leads to another form of logic, called the logic of

13 | partitions.

14 |

15 | What's a partition? It's a way of chopping the set \\(X\\) into

16 | "parts". We want each part to be a nonempty subset of \\(X\\), we want

17 | these parts to be disjoint, and we want their union to be all of

18 | \\(X\\). For example, here are all 52 partitions of a set with 5

19 | elements:

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 | Suppose we have a function between sets, \\(f : A \to B\\). We say a

24 | function \\(g: B \to A\\) is the **inverse** of \\(f\\) if

25 |

26 | \\[g(f(a)) = a \textrm{ for all } a \in A \quad \textrm{ and } \quad f(g(b)) = b \textrm{ for all } b \in B\\]

27 |

28 | Another equivalent way to say this is that

29 |

30 | \\[f(a) = b \textrm{ if and only if } a = g(b)\\]

31 |

32 | for all \\(a \in A\\) and \\(b \in B\\).

33 |

34 | So, the idea is that \\(g\\) undoes \\(f\\). For example, if \\(A = B

35 | = \mathbb{R}\\) is the set of real numbers, and \\(f\\) doubles every

36 | number, then \\(f\\) has an inverse \\(g\\), which halves every

37 | number.

38 |

39 | But what if \\(A = B = \mathbb{N}\\) is the set of _natural_ numbers,

40 | and \\(f\\) doubles every natural number. This function has no

41 | inverse!

42 |

43 | So, if I say "\\(2a = 4\\); tell me \\(a\\)" you can say \\(a = 2\\).

44 | But if I say "\\(2a = 3\\); tell me \\(a\\)" you're stuck.

45 |

46 | But you can still try to give me a "best approximation" to the

47 | nonexistent natural number \\(a\\) with \\(2 a = 3\\).

48 |

49 | "Best" in what sense? We could look for the number \\(a\\) that makes

50 | \\(2a\\) as close as possible to 3. There are two equally good

51 | options: \\(a = 1\\) and \\(a = 2\\). Here we are using the usual

52 | distance function, or

53 | [metric](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metric_(mathematics)), on

54 | \\(\mathbb{N}\\), which says that the distance between \\(x\\) and

55 | \\(y\\) is \\(|x-y|\\).

56 |

57 | But we're not talking about distance functions in this class now!

58 | We're talking about _preorders_. Can we define a "best approximation"

59 | using just the relation \\(\le\\) on \\(\mathbb{N}\\)?

60 |

61 | Yes! But we can do it in two ways!

62 |

63 | **Best approximation from below.** Find the largest possible \\(a \in

64 | \mathbb{N}\\) such that \\(2a \le 3\\). Answer: \\(a = 1\\).

65 |

66 | **Best approximation from above.** Find the smallest possible \\(a \in

67 | \mathbb{N}\\) such that \\(3 \le 2a\\). Answer: \\(a = 2\\).

68 |

69 | Okay, now work this out more generally:

70 |

71 | **Puzzle 14.** Find the function \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\)

72 | such that \\(g(b) \\) is the largest possible natural number \\(a\\)

73 | with \\(2a \le b\\).

74 |

75 | **Puzzle 15.** Find the function \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\)

76 | such that \\(g(b)\\) is the smallest possible natural number \\(a\\)

77 | with \\(b \le 2a\\).

78 |

79 | Now think about [Lecture 4](lecture_4.md) and the puzzles there! I'll

80 | copy them here with notation that better matches what I'm using now:

81 |

82 | **Puzzle 12.** Find a right adjoint for the function \\(f: \mathbb{N}

83 | \to \mathbb{N}\\) that doubles natural numbers: that is, a function

84 | \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) with

85 |

86 | \\[f(a) \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le g(b)\\]

87 |

88 | for all \\(a,b \in \mathbb{N}\\).

89 |

90 | **Puzzle 13.** Find a left adjoint for the same function \\(f\\): that

91 | is, a function \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) with

92 |

93 | \\[g(b) \le a \textrm{ if and only if } b \le f(a)\\]

94 |

95 | Next:

96 |

97 | **Puzzle 16.** What's going on here? What's the pattern you see, and

98 | why is it working this way?

99 |

100 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

101 |

102 | ---

103 |

104 | [Click here to read the original

105 | discussion](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1845/lecture-5-chapter-1-galois-connections/p1)

106 |

107 | ---

108 |

109 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

110 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_6.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 6 - Computing Adjoints

2 | ---

3 | I've already said that left and right adjoints give _the best

4 | approximate ways to solve a problem that has no solution_, namely

5 | finding the inverse of a monotone function that has no inverse. I've

6 | defined them and given you some puzzles about them. But now let's

7 | review these puzzles and extract some valuable lessons!

8 |

9 | We took the function \\(f : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\) that doubles

10 | any natural number

11 |

12 | \\[f(a) = 2a .\\]

13 |

14 | This function has no inverse, since you can't divide an odd number by

15 | 2 and get a natural number! But if you did the puzzles, you saw that

16 | \\(f\\) has a "right adjoint" \\(g : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\\).

17 | This is defined by the property

18 |

19 | \\[f(a) \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le g(b) .\\]

20 |

21 | or in other words,

22 |

23 | \\[2a \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le g(b) .\\]

24 |

25 | Using our knowledge of fractions, we have

26 |

27 | \\[2a \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le b/2\\]

28 |

29 | but since \\(a\\) is a natural number, this implies

30 |

31 | \\[2a \le b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le \lfloor b/2 \rfloor\\]

32 |

33 | where we are using the [floor

34 | function](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Floor_and_ceiling_functions)

35 | to pick out the largest integer \\(\le b/2\\). So,

36 |

37 | \\[g(b) = \lfloor b/2 \rfloor.\\]

38 |

39 | Moral: the right adjoint \\(g\\) is the "best approximation from

40 | below" to the nonexistent inverse of \\(f\\).

41 |

42 | If you did the puzzles, you also saw that \\(f\\) has a left adjoint!

43 | This is the "best approximation from above" to the nonexistent inverse

44 | of \\(f\\): it gives you the smallest integer that's \\(\ge n/2\\).

45 |

46 | So, while \\(f\\) has no inverse, it has two "approximate inverses".

47 | The left adjoint comes as close as possible to the (perhaps

48 | nonexistent) correct answer while making sure to never choose a number

49 | that's _too small_. The right adjoint comes as close as possible while

50 | making sure to never choose a number that's _too big_.

51 |

52 | The two adjoints represent two opposing philosophies of life: _make

53 | sure you never ask for too little_ and _make sure you never ask for

54 | too much_. This is why they're philosophically profound. But the great

55 | thing is that they are defined in a completely precise, systematic way

56 | that applies to a huge number of situations!

57 |

58 | If you need a mnemonic to remember which is which, remember left

59 | adjoints are "left-wing" or "liberal" or "generous", while right

60 | adjoints are "right-wing" or "conservative" or "cautious".

61 |

62 | Let's think a bit more about how we can compute them in general,

63 | starting from the basic definition.

64 |

65 | Here's the definition again. Suppose we have two preorders

66 | \\((A,\le_A)\\) and \\((B,\le_B)\\) and a monotone function \\(f : A

67 | \to B\\). Then we say a monotone function \\(g: B \to A\\) is a

68 | **right adjoint of \\(f\\)** if

69 |

70 | \\[f(a) \le_B b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le_A g(b)\\]

71 |

72 | for all \\(a \in A\\) and \\(b \in B\\). In this situation we also say

73 | that \\(f\\) is a **left adjoint of \\(g\\)**.

74 |

75 | The names should be easy to remember, since \\(f\\) shows up on the

76 | _left_ of the inequality $$f(a) \le_B b$$, while \\(g\\) shows up on

77 | the _right_ of the inequality \\(a \le_A g(b)\\). But let's see how

78 | they actually work!

79 |

80 | Suppose you know \\(f : A \to B\\) and you're trying to figure out its

81 | right adjoint \\(g: B \to A\\). Say you're trying to figure out

82 | \\(g(b)\\). You don't know what it is, but you know

83 |

84 | \\[f(a) \le_B b \textrm{ if and only if } a \le_A g(b)\\]

85 |

86 | So, you go around looking at choices of \\(a \in A\\). For each one

87 | you compute \\(f(a)\\). If \\(f(a) \le_B b\\), then you know \\(a

88 | \le_A g(b)\\). So, you need to choose \\(g(b)\\) to be greater than or

89 | equal to every element of this set:

90 |

91 | \\[\{a \in A : \; f(a) \le_B b \}\\]

92 |

93 | In other words, \\(g(b)\\) must be an **[upper

94 | bound](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_and_lower_bounds)** of this

95 | set. But you shouldn't choose \\(g(b)\\) to be any bigger than it

96 | needs to be! After all, you know $$a \le_A g(b)$$ _only if_ $$f(a)

97 | \le_B b$$. So, \\(g(b)\\) must be a **[least upper

98 | bound](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infimum_and_supremum)** of the

99 | above set.

100 |

101 | Note that I'm carefully speaking about _a_ least upper bound. Our set

102 | could have two different least upper bounds, say \\(a\\) and \\(a'\\).

103 | Since they're both the least, we must have \\(a \le a'\\) and \\(a'

104 | \le a\\). This doesn't imply \\(a = a'\\), in general! But it does if

105 | our preorder \\(A\\) is a "poset". A **poset** is a preorder \\((A,

106 | \le_A)\\) obeying this extra axiom:

107 |

108 | \\[\textrm{ if } a \le a' \textrm{ and } a' \le a \textrm{ then } a = a'\\]

109 |

110 | for all \\(a,a' \in A\\).

111 |

112 | In a poset, our desired least upper bound may still not _exist_. But

113 | if it does, it's _unique_, and Fong and Spivak write it this way:

114 |

115 | \\[\bigvee \{a \in A : \; f(a) \le_B b \}\\]

116 |

117 | The \\(\bigvee\\) symbol stands for "least upper bound", also known as

118 | **supremum** or **join**.

119 |

120 | So, here's what we've shown:

121 |

122 | If \\(f : A \to B\\) has a right adjoint \\(g : B \to A\\) and \\(A\\)

123 | is a poset, this right adjoint is unique and we have a formula for it:

124 |

125 | \\[g(b) = \bigvee \{a \in A : \; f(a) \le_B b \} .\\]

126 |

127 | And we can copy our whole line of reasoning and show this:

128 |

129 | If \\(g : B \to A\\) has a left adjoint \\(f : A \to B\\) and \\(B\\)

130 | is a poset, this left adjoint is unique and we have a formula for it:

131 |

132 | \\[f(a) = \bigwedge \{b \in B : \; a \le_A g(b)\}.\\]

133 |

134 | Here the \\(\bigwedge\\) symbol stands for "greatest lower bound",

135 | also known as the **infimum** or **meet**.

136 |

137 | We're making progress: we can now actually compute left and right

138 | adjoints! Next we'll start looking at more examples.

139 |

140 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

141 |

142 | ---

143 |

144 | [Click here to read the original discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1901/lecture-6-chapter-1-computing-adjoints/p1)

145 |

146 | ---

147 |

148 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

149 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_10.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 10 - The Logic of Partitions

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

5 | I've been explaining how we can create a version of logic starting

6 | from any poset, which we think of as a poset of "propositions". There

7 | are various ways to get our hands on such a poset. One way is to start

8 | with a set \\(X\\) and build a poset \\(P(X)\\) whose elements are

9 | subsets of \\(X\\). This leads to the most traditional form of logic,

10 | called classical logic. But another way is to start with a set \\(X\\)

11 | and build a poset \\(\mathcal{E}(X)\\) whose elements are "partitions"

12 | of \\(X\\). This leads to another form of logic, called the logic of

13 | partitions.

14 |

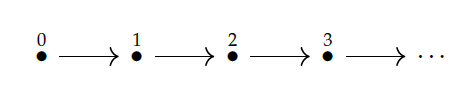

15 | What's a partition? It's a way of chopping the set \\(X\\) into

16 | "parts". We want each part to be a nonempty subset of \\(X\\), we want

17 | these parts to be disjoint, and we want their union to be all of

18 | \\(X\\). For example, here are all 52 partitions of a set with 5

19 | elements:

20 |

21 |  22 |

23 | At the top we see the "coarsest" partition, where all 5 elements are

24 | in the same part. At the bottom we see the "finest" partition, where

25 | each element is in its own separate part.

26 |

27 | How can we think of these partitions as "propositions"? Here's how:

28 | each partition gives a proposition saying that two elements in the

29 | same part are "equivalent", or the same in some way. The coarser the

30 | partition, the more elements are equivalent.

31 |

32 | For example, imagine you're a detective trying to solve a case on a

33 | small island with 5 people on it. At first you don't know any of them

34 | are related, so they're all in separate families, as far as you know:

35 |

36 |

22 |

23 | At the top we see the "coarsest" partition, where all 5 elements are

24 | in the same part. At the bottom we see the "finest" partition, where

25 | each element is in its own separate part.

26 |

27 | How can we think of these partitions as "propositions"? Here's how:

28 | each partition gives a proposition saying that two elements in the

29 | same part are "equivalent", or the same in some way. The coarser the

30 | partition, the more elements are equivalent.

31 |

32 | For example, imagine you're a detective trying to solve a case on a

33 | small island with 5 people on it. At first you don't know any of them

34 | are related, so they're all in separate families, as far as you know:

35 |

36 |  37 |

38 | But then you start digging into their history. Each time you learn

39 | that two people are related, you change your partition by putting them

40 | into the same part:

41 |

42 |

37 |

38 | But then you start digging into their history. Each time you learn

39 | that two people are related, you change your partition by putting them

40 | into the same part:

41 |

42 |  43 |

44 | You keep doing this as secret family relationships are revealed:

45 |

46 |

43 |

44 | You keep doing this as secret family relationships are revealed:

45 |

46 |  47 |

48 | In this example, as you learn more you move to _coarser_ partitions,

49 | because your goal is to find relationships between people, and lump

50 | them in as big bunches as possible. But often people think about

51 | partition logic a bit differently, where as you learn more you move to

52 | _finer_ partitions.

53 |

54 | Suppose you are an amateur wine taster learning to distinguish

55 | different kinds of wine by their taste. At first all wines taste

56 | alike, so they're all lumped together:

57 |

58 |

47 |

48 | In this example, as you learn more you move to _coarser_ partitions,

49 | because your goal is to find relationships between people, and lump

50 | them in as big bunches as possible. But often people think about

51 | partition logic a bit differently, where as you learn more you move to

52 | _finer_ partitions.

53 |

54 | Suppose you are an amateur wine taster learning to distinguish

55 | different kinds of wine by their taste. At first all wines taste

56 | alike, so they're all lumped together:

57 |

58 |  59 |

60 | When you learn to distinguish red and white wines, you move to a finer

61 | partition:

62 |

63 |

59 |

60 | When you learn to distinguish red and white wines, you move to a finer

61 | partition:

62 |

63 |  64 |

65 | This sort of example will fit our story a bit better. We'll generally

66 | say that you know more if your partition is _finer_.

67 |

68 | Now it's time to define partitions more carefully! A partition of

69 | \\(X\\) is a bunch of subsets of \\(X\\). So, it's a subset of

70 | \\(P(X)\\). Please think about that until it makes sense, or ask

71 | questions. There are a lot of sets and subsets running around: it can

72 | be confusing. But here we go:

73 |

74 | **Definition.** A **partition** of a set \\(X\\) is a set \\(P

75 | \subseteq P(X)\\) such that:

76 |

77 | 1. Each set \\(S \in P\\) is nonempty.

78 |

79 | 2. Distinct sets \\(S, T \in P\\) are disjoint: that is, if \\(S \ne

80 | T\\) then \\(S \cap T = \emptyset\\).

81 |

82 | 3. The union of all the sets \\(S \in P\\) is \\(X\\): that is,

83 |

84 | \\[X = \bigcup_{S \in P} S.\\]

85 |

86 | We call the sets \\(S \in P\\) the **parts** of the partition.

87 |

88 | I said that each partition \\(P\\) gives an equivalence relation,

89 | where two elements of \\(X\\) are "equivalent" if and only if they're

90 | in the same part. Let's make that precise too:

91 |

92 | **Definition.** An **equivalence relation** on a set \\(X\\) is a

93 | relation \\(\sim\\) on \\(X\\) that is:

94 |

95 | 1. **Reflexive:** for all \\(x \in X\\), \\(x \sim x\\).

96 |

97 | 2. **Transitive:** for all \\(x,y,z \in Z\\), \\(x \sim y\\) and \\(y

98 | \sim z\\) imply \\(x \sim z\\).

99 |

100 | 3. **Symmetric:** for all \\(x,y \in X\\), \\(x \sim y\\) implies \\(y

101 | \sim x.\\)

102 |

103 | **Puzzle 28.** Show that if \\(P\\) is a partition of a set \\(X\\),

104 | and we define a relation \\(\sim_P\\) on \\(X\\) as follows:

105 |

106 | \\[x \sim_P y \textrm{ if and only if } x, y \in S \textrm{ for some } S \in P,\\]

107 |

108 | then \\(\sim_P\\) is an equivalence relation.

109 |

110 | **Puzzle 29.** Show that if \\(\sim\\) is an equivalence relation on a

111 | set \\(X\\), we can define a partition \\(P_\sim\\) on \\(X\\) whose

112 | parts are precisely the sets of the form

113 |

114 | \\[S_x = \\{y \in X : \; y \sim x \\}\\]

115 |

116 | with \\(x \in X\\). We call \\(S_x\\) the **equivalence class** of

117 | \\(x\\).

118 |

119 | **Puzzle 31.** Show that the previous two puzzles give a one-to-one

120 | correspondence between partitions of \\(X\\) and equivalence relations

121 | on \\(X\\).

122 |

123 | **Puzzle 32.** Proposition 1.11 of _[Seven

124 | Sketches](http://math.mit.edu/~dspivak/teaching/sp18/7Sketches.pdf)_

125 | asserts that there is a one-to-one correspondence between partitions

126 | of \\(X\\) and equivalence relations on \\(X\\). However, in the

127 | current version of the book this proposition is false! Nonetheless,

128 | the statement in Puzzle 31 is correct. How is this possible? (Hint:

129 | you have to read their definitions quite carefully. This is good

130 | practice in reading mathematics.)

131 |

132 | **Puzzle 33.** Is an equivalence relation always a preorder?

133 |

134 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

135 |

136 | ---

137 |

138 | [Click here to read the original discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1963/lecture-10-chapter-1-the-logic-of-partitions/p1)

139 |

140 | ---

141 |

142 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

143 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_12.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 12 - Generative Effects

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

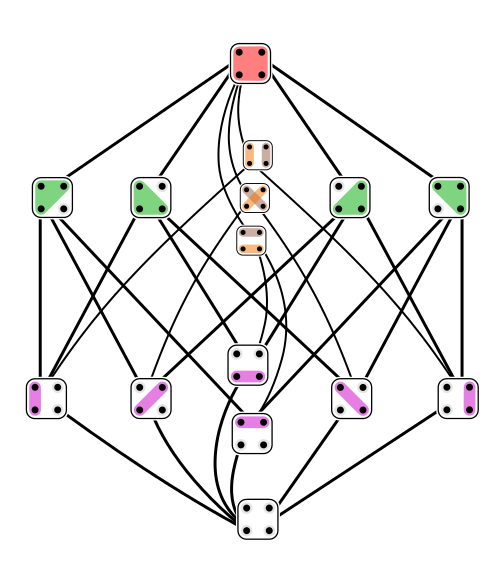

5 | We now reach a topic highlighted by Fong and Spivak: "generative

6 | effects". These are, roughly, situations where the whole is more than

7 | the sum of its parts. A nice example shows up in the logic of

8 | partitions.

9 |

10 | Remember that any set \\(X\\) has a poset of partitions. This poset is

11 | called \\(\mathcal{E}(X)\\), and its elements are partitions of

12 | \\(X\\). Each partition \\(P\\) corresponds to an equivalence relation

13 | \\(\sim_P\\), where \\(x \sim_P y\\) if and only if \\(x\\) and

14 | \\(y\\) are in the same part of \\(P\\). This makes it easy to

15 | describe the partial order on \\(\mathcal{E}(X)\\): we say a partition

16 | \\(P\\) is **finer** than a partition \\(Q\\), or \\(Q\\) is

17 | **coarser** than \\(P\\), or simply \\(P \le Q\\), when

18 |

19 | \\[ x \sim_P y \textrm{ implies } x \sim_Q y \\]

20 |

21 | for all \\(x,y \in X\\).

22 |

23 | Now that we have this poset, how can we do _logic_ with it?

24 |

25 | In the logic of subsets, we've seen that "and" and "or" are the

26 | operations of "meet" and "join" in a certain poset. So, the logic of

27 | partitions should use "meet" and "join" in the poset

28 | \\(\mathcal{E}(X)\\). Let's see what they're like!

29 |

30 | First, we can ask whether two partitions \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) have a

31 | meet. Remember: the **meet** \\(P \wedge Q\\), if it exists, is the

32 | coarsest partition that is finer than \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\).

33 |

34 | **Puzzle 34.** Can you draw the coarsest partition that's finer than

35 | these two partitions?

36 |

37 |

64 |

65 | This sort of example will fit our story a bit better. We'll generally

66 | say that you know more if your partition is _finer_.

67 |

68 | Now it's time to define partitions more carefully! A partition of

69 | \\(X\\) is a bunch of subsets of \\(X\\). So, it's a subset of

70 | \\(P(X)\\). Please think about that until it makes sense, or ask

71 | questions. There are a lot of sets and subsets running around: it can

72 | be confusing. But here we go:

73 |

74 | **Definition.** A **partition** of a set \\(X\\) is a set \\(P

75 | \subseteq P(X)\\) such that:

76 |

77 | 1. Each set \\(S \in P\\) is nonempty.

78 |

79 | 2. Distinct sets \\(S, T \in P\\) are disjoint: that is, if \\(S \ne

80 | T\\) then \\(S \cap T = \emptyset\\).

81 |

82 | 3. The union of all the sets \\(S \in P\\) is \\(X\\): that is,

83 |

84 | \\[X = \bigcup_{S \in P} S.\\]

85 |

86 | We call the sets \\(S \in P\\) the **parts** of the partition.

87 |

88 | I said that each partition \\(P\\) gives an equivalence relation,

89 | where two elements of \\(X\\) are "equivalent" if and only if they're

90 | in the same part. Let's make that precise too:

91 |

92 | **Definition.** An **equivalence relation** on a set \\(X\\) is a

93 | relation \\(\sim\\) on \\(X\\) that is:

94 |

95 | 1. **Reflexive:** for all \\(x \in X\\), \\(x \sim x\\).

96 |

97 | 2. **Transitive:** for all \\(x,y,z \in Z\\), \\(x \sim y\\) and \\(y

98 | \sim z\\) imply \\(x \sim z\\).

99 |

100 | 3. **Symmetric:** for all \\(x,y \in X\\), \\(x \sim y\\) implies \\(y

101 | \sim x.\\)

102 |

103 | **Puzzle 28.** Show that if \\(P\\) is a partition of a set \\(X\\),

104 | and we define a relation \\(\sim_P\\) on \\(X\\) as follows:

105 |

106 | \\[x \sim_P y \textrm{ if and only if } x, y \in S \textrm{ for some } S \in P,\\]

107 |

108 | then \\(\sim_P\\) is an equivalence relation.

109 |

110 | **Puzzle 29.** Show that if \\(\sim\\) is an equivalence relation on a

111 | set \\(X\\), we can define a partition \\(P_\sim\\) on \\(X\\) whose

112 | parts are precisely the sets of the form

113 |

114 | \\[S_x = \\{y \in X : \; y \sim x \\}\\]

115 |

116 | with \\(x \in X\\). We call \\(S_x\\) the **equivalence class** of

117 | \\(x\\).

118 |

119 | **Puzzle 31.** Show that the previous two puzzles give a one-to-one

120 | correspondence between partitions of \\(X\\) and equivalence relations

121 | on \\(X\\).

122 |

123 | **Puzzle 32.** Proposition 1.11 of _[Seven

124 | Sketches](http://math.mit.edu/~dspivak/teaching/sp18/7Sketches.pdf)_

125 | asserts that there is a one-to-one correspondence between partitions

126 | of \\(X\\) and equivalence relations on \\(X\\). However, in the

127 | current version of the book this proposition is false! Nonetheless,

128 | the statement in Puzzle 31 is correct. How is this possible? (Hint:

129 | you have to read their definitions quite carefully. This is good

130 | practice in reading mathematics.)

131 |

132 | **Puzzle 33.** Is an equivalence relation always a preorder?

133 |

134 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

135 |

136 | ---

137 |

138 | [Click here to read the original discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1963/lecture-10-chapter-1-the-logic-of-partitions/p1)

139 |

140 | ---

141 |

142 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

143 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_12.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Lecture 12 - Generative Effects

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

5 | We now reach a topic highlighted by Fong and Spivak: "generative

6 | effects". These are, roughly, situations where the whole is more than

7 | the sum of its parts. A nice example shows up in the logic of

8 | partitions.

9 |

10 | Remember that any set \\(X\\) has a poset of partitions. This poset is

11 | called \\(\mathcal{E}(X)\\), and its elements are partitions of

12 | \\(X\\). Each partition \\(P\\) corresponds to an equivalence relation

13 | \\(\sim_P\\), where \\(x \sim_P y\\) if and only if \\(x\\) and

14 | \\(y\\) are in the same part of \\(P\\). This makes it easy to

15 | describe the partial order on \\(\mathcal{E}(X)\\): we say a partition

16 | \\(P\\) is **finer** than a partition \\(Q\\), or \\(Q\\) is

17 | **coarser** than \\(P\\), or simply \\(P \le Q\\), when

18 |

19 | \\[ x \sim_P y \textrm{ implies } x \sim_Q y \\]

20 |

21 | for all \\(x,y \in X\\).

22 |

23 | Now that we have this poset, how can we do _logic_ with it?

24 |

25 | In the logic of subsets, we've seen that "and" and "or" are the

26 | operations of "meet" and "join" in a certain poset. So, the logic of

27 | partitions should use "meet" and "join" in the poset

28 | \\(\mathcal{E}(X)\\). Let's see what they're like!

29 |

30 | First, we can ask whether two partitions \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) have a

31 | meet. Remember: the **meet** \\(P \wedge Q\\), if it exists, is the

32 | coarsest partition that is finer than \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\).

33 |

34 | **Puzzle 34.** Can you draw the coarsest partition that's finer than

35 | these two partitions?

36 |

37 |  39 |

40 | In fact the meet of two partitions always exists, and it's easy to

41 | describe:

42 |

43 | **Puzzle 35.** Suppose \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) are two partitions of a set

44 | \\(X\\). Show that there's an equivalence relation \\(\approx\\)

45 | defined by

46 |

47 | \\[ x \approx y \textrm{ if and only if } x \sim_P y \textrm{ and } x

48 | \sim_Q y . \\]

49 |

50 | **Puzzle 36.** Every equivalence relation gives a partition as in

51 | [Puzzle

52 | 29](lecture_10.md).

53 | Show that \\(\approx\\) gives the partition \\(P \wedge Q\\).

54 |

55 | We can also ask whether \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) have a join! The **join**

56 | \\(P \vee Q\\), if it exists, is the finest partition that is coarser

57 | than \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\).

58 |

59 | Can you draw the finest partition that's coarser than these two

60 | partitions?

61 |

62 |

39 |

40 | In fact the meet of two partitions always exists, and it's easy to

41 | describe:

42 |

43 | **Puzzle 35.** Suppose \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) are two partitions of a set

44 | \\(X\\). Show that there's an equivalence relation \\(\approx\\)

45 | defined by

46 |

47 | \\[ x \approx y \textrm{ if and only if } x \sim_P y \textrm{ and } x

48 | \sim_Q y . \\]

49 |

50 | **Puzzle 36.** Every equivalence relation gives a partition as in

51 | [Puzzle

52 | 29](lecture_10.md).

53 | Show that \\(\approx\\) gives the partition \\(P \wedge Q\\).

54 |

55 | We can also ask whether \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) have a join! The **join**

56 | \\(P \vee Q\\), if it exists, is the finest partition that is coarser

57 | than \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\).

58 |

59 | Can you draw the finest partition that's coarser than these two

60 | partitions?

61 |

62 |  64 |

65 | To check your answer, see our discussion of [Exercise

66 | 2](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1872/exercise-2-chapter-1).

67 |

68 | The join of two partitions always exists. Since "and" and "or" are

69 | meet and join in the logic of subsets, you might think the to describe

70 | the join of partitions, we just copy Puzzle 35 and replace "and" with

71 | "or". _But no!_

72 |

73 | **Puzzle 37.** Suppose \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) are two partitions. Show

74 | that the relation \\(\frown\\) defined by

75 |

76 | \\[ x \frown y \textrm{ if and only if } x \sim_P y \textrm{ or } x

77 | \sim_Q y \\]

78 |

79 | is _not always_ an equivalence relation.

80 |

81 | To get the equivalence relation corresponding to \\(P \vee Q\\), we

82 | have to work harder. Say we have any partitions \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) of

83 | some set \\(X\\). If you give me two elements \\(x, y \in X\\) and ask

84 | if they're in the same part of \\(P \vee Q\\), it's _not enough_ to

85 | check whether

86 |

87 | \\[ x \textrm{ and } y \textrm{ are in the same part of } P \textrm{

88 | or the same part of } Q . \\]

89 |

90 | (That's what \\(x \frown y\\) means.) Instead, you have to check

91 | whether there's a _list_ of elements \\(z_1, \dots, z_n\\) such that

92 |

93 | \\[ x \textrm{ and } z_1 \textrm{ are in the same part of } P \textrm{

94 | or the same part of } Q \\]

95 |

96 | and

97 |

98 | \\[ z_1 \textrm{ and } z_2 \textrm{ are in the same part of } P

99 | \textrm{ or the same part of } Q \\]

100 |

101 | and so on, and finally

102 |

103 | \\[ z_n \textrm{ and } y \textrm{ are in the same part of } P \textrm{

104 | or the same part of } Q . \\]

105 |

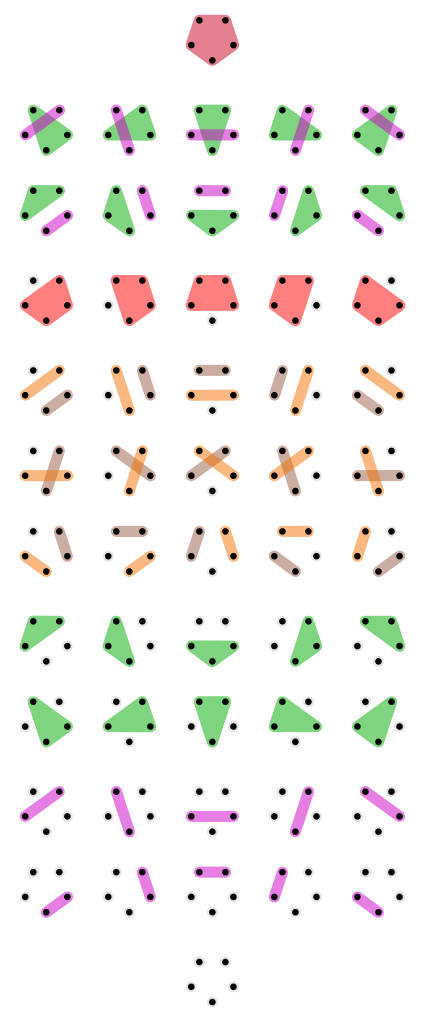

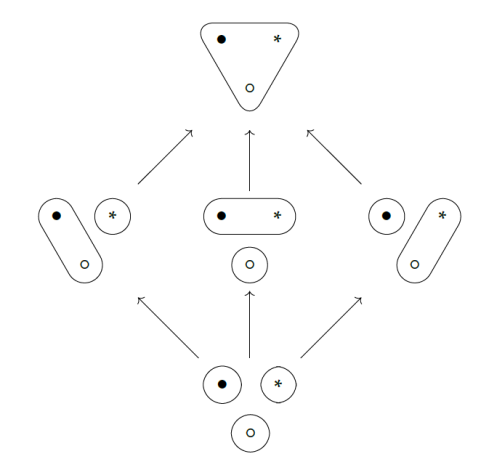

106 | This picture by [Michael

107 | Hong](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1855/introduction-michael-hong)

108 | shows how it works:

109 |

110 |

64 |

65 | To check your answer, see our discussion of [Exercise

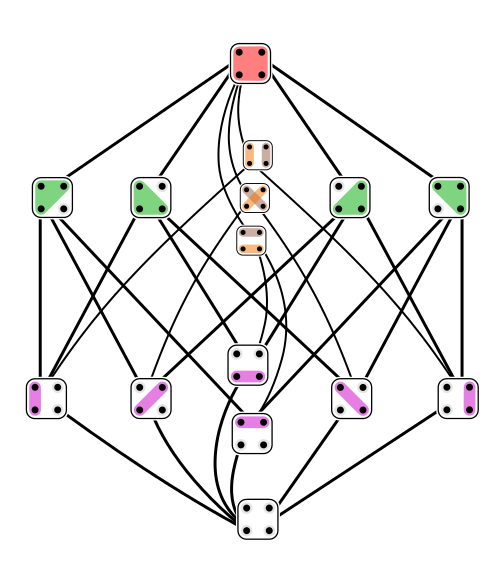

66 | 2](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1872/exercise-2-chapter-1).

67 |

68 | The join of two partitions always exists. Since "and" and "or" are

69 | meet and join in the logic of subsets, you might think the to describe

70 | the join of partitions, we just copy Puzzle 35 and replace "and" with

71 | "or". _But no!_

72 |

73 | **Puzzle 37.** Suppose \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) are two partitions. Show

74 | that the relation \\(\frown\\) defined by

75 |

76 | \\[ x \frown y \textrm{ if and only if } x \sim_P y \textrm{ or } x

77 | \sim_Q y \\]

78 |

79 | is _not always_ an equivalence relation.

80 |

81 | To get the equivalence relation corresponding to \\(P \vee Q\\), we

82 | have to work harder. Say we have any partitions \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) of

83 | some set \\(X\\). If you give me two elements \\(x, y \in X\\) and ask

84 | if they're in the same part of \\(P \vee Q\\), it's _not enough_ to

85 | check whether

86 |

87 | \\[ x \textrm{ and } y \textrm{ are in the same part of } P \textrm{

88 | or the same part of } Q . \\]

89 |

90 | (That's what \\(x \frown y\\) means.) Instead, you have to check

91 | whether there's a _list_ of elements \\(z_1, \dots, z_n\\) such that

92 |

93 | \\[ x \textrm{ and } z_1 \textrm{ are in the same part of } P \textrm{

94 | or the same part of } Q \\]

95 |

96 | and

97 |

98 | \\[ z_1 \textrm{ and } z_2 \textrm{ are in the same part of } P

99 | \textrm{ or the same part of } Q \\]

100 |

101 | and so on, and finally

102 |

103 | \\[ z_n \textrm{ and } y \textrm{ are in the same part of } P \textrm{

104 | or the same part of } Q . \\]

105 |

106 | This picture by [Michael

107 | Hong](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1855/introduction-michael-hong)

108 | shows how it works:

109 |

110 |  112 |

113 | So, the join is a lot more complicated than the meet!

114 |

115 | **Puzzle 38.** If \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) are two partitions on a set

116 | \\(X\\), let the relation \\(\simeq\\) be the **[transitive

117 | closure](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transitive_closure)** of the

118 | relation \\(\frown\\) defined in Puzzle 37. This means that \\(x

119 | \simeq y\\) if and only if

120 |

121 | $$ x \frown z_1 \textrm{ and } z_1 \frown z_2 \textrm{ and } \dots

122 | \textrm{ and } z_{n-1} \frown z_n \textrm{ and } z_n \frown y $$

123 |

124 | for some \\(z_1, \dots, z_n \in X\\). Show that \\(\simeq\\) is an

125 | equivalence relation.

126 |

127 | **Puzzle 39.** Show that the equivalence relation \\(\simeq\\) on

128 | \\(X\\) gives the partition \\(P \vee Q\\).

129 |

130 | This is the first hint of what Fong and Spivak call a "generative

131 | effect". To decide if two elements \\(x , x' \in X\\) are in the same

132 | part of the meet \\(P \wedge Q\\), it's enough to know if they're the

133 | same part of \\(P\\) and the same part of \\(Q\\), since

134 |

135 | \\[ x \sim_{P \wedge Q} x' \textrm{ if and only if } x \sim_P x'

136 | \textrm{ and } x \sim_Q x'. \\]

137 |

138 | But this does _not_ work for the join!

139 |

140 | \\[ \textbf{THIS IS FALSE: } \; x \sim_{P \vee Q} x' \textrm{ if and

141 | only if } x \sim_P x' \textrm{ or } x \sim_Q x' . \\]

142 |

143 | To decide if $$x \sim_{P \vee Q} y$$ you need to look at _other_

144 | elements of \\(X\\), too. It's not a "local" calculation - it's a

145 | "global" one!

146 |

147 | But to make this really precise and clear, we need to think about

148 | "pulling back" partitions. We'll do that next time.

149 |

150 | **[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

151 |

152 | ---

153 |

154 | [Click here to read the original discussion.](https://forum.azimuthproject.org/discussion/1999/lecture-12-chapter-1-generative-effects/p1)

155 |

156 | ---

157 |

158 | {% include "../LICENSE.md" %}

159 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/chapter_1/lecture_11.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

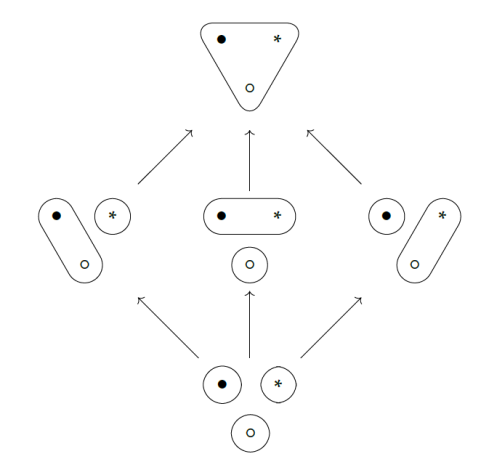

1 | # Lecture 11 - The Poset of Partitions

2 |

3 | ---

4 |

5 | Last time we learned about _partitions_ of a set: ways of chopping it

6 | into disjoint nonempty sets called "parts".

7 |

8 |

112 |

113 | So, the join is a lot more complicated than the meet!

114 |

115 | **Puzzle 38.** If \\(P\\) and \\(Q\\) are two partitions on a set

116 | \\(X\\), let the relation \\(\simeq\\) be the **[transitive

117 | closure](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transitive_closure)** of the

118 | relation \\(\frown\\) defined in Puzzle 37. This means that \\(x

119 | \simeq y\\) if and only if

120 |

121 | $$ x \frown z_1 \textrm{ and } z_1 \frown z_2 \textrm{ and } \dots

122 | \textrm{ and } z_{n-1} \frown z_n \textrm{ and } z_n \frown y $$

123 |

124 | for some \\(z_1, \dots, z_n \in X\\). Show that \\(\simeq\\) is an

125 | equivalence relation.

126 |

127 | **Puzzle 39.** Show that the equivalence relation \\(\simeq\\) on

128 | \\(X\\) gives the partition \\(P \vee Q\\).

129 |

130 | This is the first hint of what Fong and Spivak call a "generative

131 | effect". To decide if two elements \\(x , x' \in X\\) are in the same

132 | part of the meet \\(P \wedge Q\\), it's enough to know if they're the

133 | same part of \\(P\\) and the same part of \\(Q\\), since

134 |

135 | \\[ x \sim_{P \wedge Q} x' \textrm{ if and only if } x \sim_P x'

136 | \textrm{ and } x \sim_Q x'. \\]

137 |

138 | But this does _not_ work for the join!

139 |

140 | \\[ \textbf{THIS IS FALSE: } \; x \sim_{P \vee Q} x' \textrm{ if and

141 | only if } x \sim_P x' \textrm{ or } x \sim_Q x' . \\]

142 |