├── license.md

├── README.md

├── visas.md

├── H-1B1.md

├── green-card.md

├── TN.md

├── L-1.md

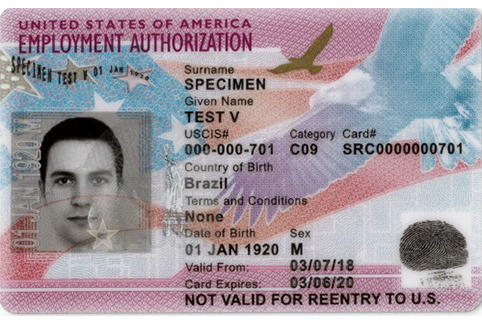

├── EAD.md

└── EB.md

/license.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | To the extent possible under law, the authors of the US Immigration FAQ have waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights

2 | to the US Immigration FAQ. See .

3 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/README.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ## Why does this FAQ exist?

2 | There are certain questions related to US immigration for tech workers that are frequently asked, either directly to Brian, or through a forum such as [Quora](https://www.quora.com/) or [Blind](http://us.teamblind.com/), as well as certain misconceptions that resurface periodically. Brian created this FAQ in order to answer those questions and correct those misconceptions the best he can, as well as to invite contributions from other people. This FAQ does not consist of legal advice, and in order to get a work visa or employment-based green card, you'll almost always need the assistance of a qualified immigration lawyer. However, we hope that the FAQ will give you a sense of what's possible and what can be expected should you make the decision to proceed down various paths, such as studying a master's degree in computer science in the United States.

3 |

4 | ## Can't the answers to these questions already be found online?

5 | In some cases, yes. Brian's personal experience is that when qualified immigration lawyers give answers online, they tend to hedge their words in order to protect their reputations, whereas answers given by people other than immigration lawyers often consist of guesswork and anecdotes, and regardless of who's answering, the answers can easily become outdated.

6 |

7 | ## Why should I believe the answers on this FAQ then?

8 | Brian believes that you should believe his answers about US immigration for the same reason why you believe his answers on other topics---not because he is some sort of "expert", but because they make sense in the context of what you already know about the topic.

9 |

10 | That being said, whenever possible, we will provide citations to the relevant statutes, regulations, and current practices, including the Immigration and Nationality Act, title 8 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the State Department's *Foreign Affairs Manual*, and the CBP Field Manual, as well as to other sources written by more qualified individuals that you may or may not consider authoritative.

11 |

12 | ## Which section of the FAQ should I read?

13 | * [general.md](general.md) for general questions about the US immigration system

14 | * [green-card.md](green-card.md) for questions about green cards and LPR status

15 | * [EB.md](EB.md) for questions specific to employment-based immigration

16 | * [H-1B.md](H-1B.md) for questions about H-1B visas/status

17 | * [H-1B1.md](H-1B1.md) for questions about H-1B1 visas/status, which shares some similarities with H-1B status but also some significant differences

18 | * [L-1.md](L-1.md) for questions about L-1A and L-1B visas/status

19 | * [TN.md](TN.md) for questions about TN visas/status

20 | * [visas.md](visas.md) for questions about visas in general (stamped into your passport by the State Department)

21 | * [EAD.md](EAD.md) for questions about Employment Authorization Documents (EADs)

22 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/visas.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | # Questions about visas

2 | Before reading this section, be sure to familiarize yourself with the [difference between a visa and a status](general.md#whats-the-difference-between-visa-and-status).

3 |

4 | ## Which foreign nationals do not need a visa to enter the US?

5 | While most foreign nationals must present a visa in order to enter the US, there are several exceptions, some of which are listed below:

6 | * Returning lawful permanent residents should present their Permanent Resident Card (green card) or certain other documents [1].

7 | * Nationals of certain countries may visit the US for business or pleasure using the [Visa Waiver Program](https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/tourism-visit/visa-waiver-program.html). Note that "business" doesn't include "work". In addition, there are several restrictions on the VWP, including:

8 | * If arriving by air or sea, you will need to apply for advance authorization [2] through [ESTA](https://esta.cbp.dhs.gov/esta/).

9 | * A foreign national who was admitted under the VWP and overstayed their visit becomes permanently ineligible for the VWP [3]. This means they will need a visa in the future unless they qualify for some other exemption.

10 | * Similarly, aliens previously removed from the US are permanently ineligible for the VWP [4].

11 | * Being refused a visa or admission to the United States makes it unlikely, but not impossible, to qualify under the VWP in the future. [5]

12 | * Foreign nationals admitted under the VWP are ineligible for extension of stay [6], change of nonimmigrant status [7], and adjustment of status unless as the immediate relative of a US citizen [8].

13 | * Canadian and Bermudian citizens seeking admission as nonimmigrants using their Canadian or Bermudian passport are visa-exempt unless they are seeking admission in E, K, S, or V status [9]. The restrictions described above on the Visa Waiver Program do not apply to Canadians and Bermudians. However, Canadians and Bermudians cannot simply stroll into the US. If they want to be admitted in a status that requires additional documentation, such as F-1 or H-1B status, they must still present the required documentation at the port of entry.

14 | * Mexican nationals seeking to visit the US for short periods of time can use their Border Crossing Card [10], but this is not really an exception since a Border Crossing Card can also be used as a B-1/B-2 visa.

15 |

16 | ## Can I renew a visa while in the US?

17 | The expiration of your visa has no bearing on whether or not you may remain in the United States. However, nonimmigrants who aren't visa-exempt (see above) will need to present a visa the next time they leave and re-enter the US. Nonimmigrants who have made the US their home and who don't want to be stranded outside the US are often interested in knowing whether it's possible to renew their visa while they're still in the US, so that they can depart the US with a new visa already secured. Unfortunately, with very few exceptions, visas can only be issued outside the US at a consular post [12]. Even though federal regulations theoretically allow renewal of an E, H, I, L, O, or P visa while in the US, it doesn't seem that that option is currently available. Therefore, all H-1B, L-1, and other temporary workers in the US, other than those who are visa-exempt, should be prepared for the possibility that delays in obtaining a new visa will delay their return to the US after a trip abroad.

18 |

19 | ## Does a visa expire when the passport holding it expires?

20 | No. A US visa remains valid until its indicated expiration date or until it is cancelled or revoked, even if the containing passport expires. The holder of the expired passport with the visa still in it can use that visa together with an unexpired passport bearing the same name. [13]

21 |

22 | ## Under which circumstances can an expired visa be used to enter the US?

23 | Some nonimmigrants with expired visas can return to the US using the expired visa after a visit solely to foreign contiguous territory or adjacent islands for 30 days or less. It may be possible to take advantage of this provision even if the expired passport is for a different nonimmigrant classification than the one you hold at the time of departure and in which you intend to return. The regulations for so-called "automatic revalidation" are set out in [22 CFR §41.112(d)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/22/41.112#d) and [8 CFR 214.1(b)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/214.1#b). For a more readable overview, see [here](https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/visa-information-resources/visa-expiration-date/auto-revalidate.html).

24 |

25 | **Note that automatic visa revalidation can never be used to extend status!** The relevant regulations permit the nonimmigrant to apply for readmission within the authorized period of initial admission or extension of stay

, meaning that the nonimmigrant may apply at the port of entry to *resume* their previous period of admission, which had been granted by an admission or an extension of stay. In effect, the nonimmigrant who uses automatic revalidation is asking CBP to allow them to resume their most recent I-94. A nonimmigrant who wishes to stay longer must either file for an extension with USCIS, or apply for readmission without using automatic visa revalidation. In this latter case, citizens of most countries will need an unexpired visa with the correct classification.

26 |

27 | ## Do I need a visa to attend a job interview in the US?

28 | Attending a job interview is not "work", and is a permitted activity for visitors to the US. This means you don't need sponsorship from the company you're applying to merely to attend the job interview, and you may qualify for one of the visa exemptions listed above; for example, Canadians interviewing in the US only need their passport, while most Europeans will only need their passport and approved ESTA. Otherwise, a B-1 visa (or B-2 if the primary purpose of the trip is pleasure) is appropriate. However, you will have to leave and re-enter the US with an appropriate status (such as H-1B) in order to actually begin working. If the CBP officer believes that you're not going to comply with this rule, they will deny you entry.

29 |

30 | ## How can I apply for a nonimmigrant work visa?

31 | In most cases, this process involves both you and your sponsoring employer.

32 | 1. Your sponsoring employer must first file a petition with USCIS to establish your eligibility for one of the nonimmigrant classes eligible for employment in the US

33 | 2. Once this petition is approved, **you** can use it to apply for the corresponding visa type at a consular post; see [here](https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/employment/temporary-worker-visas.html) for instructions. Your employer does not need to be involved when you are applying for the visa itself.

34 |

35 | Those who are visa-exempt would still need the approved petition from step 1 in order to obtain the nonimmigrant status you are seeking.

36 |

37 | There are exceptions to this rule. Canadians who want to work in [TN status](TN.md) are exempt from both steps; they do not need visas, and can apply for admission at the border without any prior petition approval. (TODO: also discuss H-1B1 and E-3 visas here.)

38 |

39 | ## Can I visit Canada with a US visa?

40 | No. You need a Canadian visa, unless you're a citizen of one of the [visa-exempt countries](https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/visit-canada/entry-requirements-country.html).

41 |

42 | ## Can I visit Mexico with a US visa?

43 | Yes. If you have a valid and unexpired US visa, then you don't need a Mexican visa to visit Mexico. [11]

44 |

45 | ## Are Canadians still visa-exempt even if they've violated immigration laws or been denied admission or denied an immigration benefit?

46 | Yes. Federal regulations [9] do not appear to contemplate any exceptions to the visa exemptions enjoyed by Canadians seeking admission as nonimmigrants other than in E, K, S, or V status. Thus, being denied entry to the US, or making some other request for an immigration benefit which ends up denied, does not create a requirement for Canadians to apply for visas in the future; nor do violations, ranging from minor ones such as overstaying by a few days, to the more serious, such as engaging in unauthorized employment.

47 |

48 | Thus, as discussed previously, the rules are quite different for Canadians and other visa-exempt nationals, such as Australians; circumstances such as overstays that would force other nationals to apply for visas for future visits to the US do not have the same effect on Canadians.

49 |

50 | It is important to remember that aliens in general, including Canadians, may become inadmissible to the US if they were previously removed or committed certain severe crimes or violations of US immigration law. Even in such cases, there is no point in a Canadian trying to apply for a visa, since the application will be denied due to inadmissibility anyway. It is sometimes possible to have grounds of inadmissibility waived by filing the appropriate form. If the waiver application is approved, the Canadian is then once again eligible for visa-free entry.

51 |

52 | ## If someone is subject to a travel ban, can they still obtain a visa?

53 | Typically, a noncitizen who is inadmissible is also banned from obtaining a visa [26]. For example, if a noncitizen has accumulated enough unlawful presence in the US that they are subject to a statutory bar on re-entering the US, then that person also cannot obtain a US visa (unless their ban has been waived). They must wait out their ban period before they can be issued a visa.

54 |

55 | However, travel bans issued by the President (such as the well known Trump-era nationality bans [22][23]) fall under one specific section of the law, INA §212(f). While §212(f) gives the President authority to suspend entry of a class of noncitizens, it does **not** give the President authority to deny visas to those noncitizens. Despite this, the State Department has long taken the position that §212(f) applies to both entry *and* visa issuance, and has therefore denied visas to various noncitizens on the basis of §212(f). In other words, the State Department's position is that individuals who are subject to §212(f) travel bans are not eligible to be issued a visa, unless:

56 | * they can demonstrate that they fall under one of the exemptions in the proclamation;

57 | * they are applying for a visa in a category that is not banned by the proclamation; or

58 | * they are granted a waiver when they apply for the visa.

59 |

60 | A banned individual who applied for a visa would thus either receive an outright denial under section 212(f), or be referred to administrative processing to determine whether the individual may qualify for an exemption or waiver (for example, see [24]).

61 |

62 | We will discuss the specific case of the regional COVID-19 travel bans proclaimed during the Trump and Biden administrations. These proclamations, in general, suspended the entry of noncitizens if they had been physically present in certain countries for 14 days prior to seeking entry to the US (they were not, however, based on the nationality of the traveller). See for example [17–19]. As of Jan 1, 2022, there were no such regional proclamations in effect, although it is possible for them to be reintroduced in the future, so we will discuss the legal issues here. The State Department's policy was particularly impactful in the case of the regional COVID-19 travel bans. For example, Brazil was one of the countries subjected to a regional COVID-19 travel ban. This meant that a Brazilian citizen who already had a US visa prior to the proclamation, and who was hoping to travel to the US, would have been able to enter the US by first travelling to Mexico for 14 days and then proceeding to the US. However, a Brazilian citizen who did not already have a US visa, and was planning on travelling to Mexico and then the US, would have been refused a visa by the US embassy and consulates in Brazil during the proclamation, and would most likely not have been able to enter the US.

63 |

64 | A number of legal challenges were mounted to the State Department's policy, asserting that §212(f) may only be used to ban *entry*, and not issuance of visas (therefore, in the hypothetical situation previously discussed, the Brazilian citizen should have been able to obtain a US visa in Brazil despite the fact that they would have to spend 14 days in a non-banned country prior to using said visa). Most of these lawsuits sought injunctions allowing plaintiffs to obtain visas. On October 5, 2021, in the case *Kinsley v. Blinken*, the District Court for the District of Columbia actually concluded that the State Department's policy is unlawful (see [29]), though it stopped short of entering a [universal injunction](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_injunctions) so the State Department was not actually forced to revise its guidance. On October 25, 2021, the regional COVID-19 travel bans were replaced with Proclamation 10294, whch imposes a vaccination requirement for noncitizens from all countries [30] and explicitly states that the proclamation applies only to entry and not to visa issuance. This may indicate that the State Department's preferred method to deal with the court's ruling was to moot it out and reserve the possibility of eventually banning visa issuance again during a future presidential proclamation.

65 |

66 | Note that the Trump-era nationality bans were rescinded on January 20, 2020 [27], the immigrant visa ban [15] was rescinded on February 24, 2021 [28], and the work visa ban [16] expired at the end of March 31, 2021 [20]. These bans are no longer in effect.

67 |

68 | # References

69 | [1] [8 CFR §211.1(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/211.1#a)

70 | [2] [8 CFR §217.5(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/217.5#a)

71 | [3] INA 217(a)(7) ([8 USC §1187(a)(7)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1187#a_7))

72 | [4] [8 CFR §217.2(b)(2)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/217.2#b_2)

73 | [5] https://help.cbp.gov/app/answers/detail/a_id/1097/~/previously-denied-a-visa-or-immigration-benefit

74 | [6] [8 CFR §214.1(c)(3)(i)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/214.1#c_3_i)

75 | [7] INA 248(a)(4) ([8 USC §1258(a)(4)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1258#a_4))

76 | [8] INA 245(c)(4) ([8 USC §1255(c)(4)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1255#c))

77 | [9] [8 CFR §212.1(a)(1)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/212.1#a_1)

78 | [10] [8 CFR §212.1(c)(1)(i)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/212.1#c_1_i)

79 | [11] https://consulmex.sre.gob.mx/sanfrancisco/index.php/visas-traveling-to-mexico

80 | [12] [22 CFR §41.111](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/22/41.111)

81 | [13] [9 FAM 403.9-3(B)(4)](https://fam.state.gov/FAM/09FAM/09FAM040309.html)

82 | [14] INA 221(g) ([8 USC §1201(g)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1201#g))

83 | [15] [Proclamation Suspending Entry of Immigrants Who Present Risk to the U.S. Labor Market During the Economic Recovery Following the COVID-19 Outbreak](https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-suspending-entry-immigrants-present-risk-u-s-labor-market-economic-recovery-following-covid-19-outbreak/)

84 | [16] [Proclamation Suspending Entry of Aliens Who Present a Risk to the U.S. Labor Market Following the Coronavirus Outbreak](https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-suspending-entry-aliens-present-risk-u-s-labor-market-following-coronavirus-outbreak/)

85 | [17] [Presidential Proclamation 9984](https://www.trumpwhitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-suspension-entry-immigrants-nonimmigrants-persons-pose-risk-transmitting-2019-novel-coronavirus/)

86 | [18] [Presidential Proclamation 9992](https://www.trumpwhitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-suspension-entry-immigrants-nonimmigrants-certain-additional-persons-pose-risk-transmitting-coronavirus/)

87 | [19] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/25/proclamation-on-the-suspension-of-entry-as-immigrants-and-non-immigrants-of-certain-additional-persons-who-pose-a-risk-of-transmitting-coronavirus-disease/

88 | [20] [Presidential Proclamation 10131](https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/06/2021-00039/suspension-of-entry-of-immigrants-and-nonimmigrants-who-continue-to-present-a-risk-to-the-united)

89 | [21] (Reserved)

90 | [22] [Presidential Proclamation 9645](https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-proclamation-enhancing-vetting-capabilities-processes-detecting-attempted-entry-united-states-terrorists-public-safety-threats/)

91 | [23] [Presidential Proclamation 9983](https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-improving-enhanced-vetting-capabilities-processes-detecting-attempted-entry/)

92 | [24] https://twitter.com/gsiskind/status/1275792561454579712

93 | [25] https://www.natlawreview.com/article/update-gomez-v-trump

94 | [26] INA 212(a) ([8 USC 1182(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1182#a))

95 | [27] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/proclamation-ending-discriminatory-bans-on-entry-to-the-united-states/

96 | [28] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/02/24/a-proclamation-on-revoking-proclamation-10014/

97 | [29] https://www.immigrationissues.com/update-on-travel-ban-litigation-kinsley-v-blinken/

98 | [30] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/10/25/a-proclamation-on-advancing-the-safe-resumption-of-global-travel-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

99 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/H-1B1.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ## What's the difference between H-1B and H-1B1?

2 | The H-1B1 visa is similar to the [H-1B](H-1B.md) visa: it is a nonimmigrant visa that allows an alien to perform skilled labor temporarily for an employer in the United States. However, there are several differences, of which the most important are summarized below:

3 |

4 | * H-1B1 status is only available to citizens of Chile and Singapore.

5 | * H-1B1 quotas have never been reached.

6 | * Petitions are not required in order to obtain an H-1B1 visa.

7 | * H-1B1 status is granted in 1-year increments, whereas H-1B status is granted in 3-year increments.

8 | * There is no explicit 6-year limit on the number of times H-1B1 status can be extended.

9 | * H-1B1 workers cannot avail themselves of INA 214(n) portability.

10 | * H-1B1 status does not explicitly allow dual intent.

11 |

12 | References for the above claims are provided with the more detailed answers further down this page.

13 |

14 | ## Who qualifies for an H-1B1 visa?

15 | H-1B1 status is only available to nationals of Chile and Singapore, pursuant to free trade agreements that those countries have signed with the United States [1][2][3]. Like H-1B status, H-1B1 status is only available to an alien in a specialty occupation who is being sponsored by an employer that has filed a labor condition application with the Department of Labor [1]. The definition of "specialty occupation" for H-1B1 status [4] is very slightly different from the definition for H-1B status.

16 |

17 | As is the case with H-1B status, the "specialty occupation" criterion for H-1B1 status is subjective and it is not possible for a layman to understand the nuances of the interpretation of the statute, but an employer that frequently sponsors employees for H-1B visas for a particular role will almost certainly be able to sponsor H-1B1 visas as well, provided that their lawyers are familiar with the H-1B1 classification. As is the case with H-1B status, H-1B1 status is generally available to software engineers (for the time being) despite the fact that many software engineers do not have a bachelor's degree in computer science or a related speciality.

18 |

19 | I don't know whether increased scrutiny on H-1B applications has also affected H-1B1 applications. If you have information about this, feel free to contribute.

20 |

21 | ## Why should I apply for an H-1B1 visa as opposed to H-1B or some other work visa?

22 | For those who qualify—only Chileans and Singaporeans—the H-1B1 visa is often the most convenient choice because of the fact that its annual quota has never been reached; while there is a lottery for H-1B visas every year, there is no H-1B1 lottery. Like the H-1B visa, the H-1B1 visa [can be preferable](H-1B.md#why-should-i-apply-for-h-1b-as-opposed-to-other-work-visas) to the [L-1](L-1.md) visa because it doesn't require working for an employer outside the US for 1 year, and to the [O-1](O-1.md) visa because it is much easier to qualify for.

23 |

24 | ## What is the process to apply for an H-1B1 visa or status?

25 | Due to the terms of the free trade agreements, a petition is not required in order to obtain an H-1B1 visa [5]. However, note that the treaties did *not* grant exemptions from the requirement to obtain a [visa](visas.md) to enter the US. Thus, an alien outside the US, whose employer has filed a labor certification application with the Department of Labor, would apply for an H-1B1 visa at a consular post, submitting documents directly to the consular post rather than to USCIS [6].

26 |

27 | An alien already in the United States wishing to change status to H-1B1, however, must have Form I-129 filed on their behalf by their sponsoring employer [7]. The adjudication of Form I-129 is a two-step process, in which USCIS first determines whether the petition is approvable, then determines whether the beneficiary qualifies for the change of status sought [8]. Usually, both steps will be approved, in which case USCIS sends Form I-797A, containing an I-94 indicating the new H-1B status and authorized period of stay [9]. However, it's possible that the petition is approved while the change of status is denied—typically because USCIS has determined that the beneficiary has violated their status, making them ineligible for a change of status—and the beneficiary must usually leave the United States and apply for a visa.

28 |

29 | It should be noted that H-1B1 petitions are not eligible for premium processing [12], so leaving the US to apply for an H-1B1 visa will probably be a faster method of obtaining H-1B1 status than changing status to H-1B1 within the US (which requires the petition).

30 |

31 | ## How long does H-1B1 status last?

32 | Unlike H-1B status, H-1B1 status may only be granted for 1 year at a time, and can be extended in 1-year increments [10]. Extensions of H-1B1 status are done using Form I-129 [7]. However, there is no statutory or regulatory limit on the number of extensions that can be granted. Therefore, H-1B1 workers who have already worked in the US for 6 years in H-1B1 status can continue to extend their status.

33 |

34 | However, H-1B1 status does not allow [dual intent](general.md#what-is-dual-intent), so aliens who work in the US in H-1B1 status for many years could eventually be denied further extensions on the grounds that they seem to be an intending immigrant. For this reason, H-1B1 workers often switch to H-1B status and apply for a green card, or, in some cases, start the green card process while still in H-1B1 status. (We'll discuss the issue of dual intent further below.)

35 |

36 | ## What happens if my employer applies to extend my stay, but my I-94 expires while the petition is pending?

37 | The [general rules about I-94 expiration with a pending extension](general.md#what-happens-if-my-nonimmigrant-status-expires-while-my-change-of-status-extension-of-stay-or-adjustment-of-status-application-is-pending) apply to this scenario. Provided that the extension was timely filed and the alien did not engage in any unauthorized employment, the alien will be protected from accrual of unlawful presence as long as the extension remains pending; if it is denied after the previous I-94 expired, then unlawful presence will only begin to accrue *after* the extension petition is denied.

38 |

39 | In this scenario, for a 240 day period after the previous petition expires, the alien is authorized to continue employment with the same employer (such employment is not considered unauthorized

). Again, while the extension is pending, employment authorization continues **only for up to 240 days after the expiration of the petition** (unless the extension petition is denied) [15] Thus, as long as USCIS continues to adjudicate petitions within 240 days, there should generally be no reason for your H-1B1 employment to be interrupted, as long as the employer always files for an extension **before your I-94 expires**. However, in rare cases where the 240 day clock runs out, **you can still stay in the US, but you can't work.** This is because of the general rule about extensions mentioned in the previous paragraph.

40 |

41 | If a denial occurs during the 240 day period, then employment authorization immediately ceases since the petition is no longer pending [15].

42 |

43 | ## Can I do any work other than for my sponsoring employer?

44 | An H-1B1 worker who does not have an EAD is only permitted to work for their sponsoring employer [11]. It is permitted to work for multiple employers concurrently, but only as long as each employer wishing to employ the H-1B1 alien has met the applicable requirements. In other words, an H-1B1 alien in the United States who wants to begin new concurrent employment must wait until the new employer has had Form I-129 approved (and the new employer must have filed a labor condition application); while the Foreign Affairs Manual is not clear on this, it appears that an alien outside the United States, who already has an H-1B1 visa authorizing employment with one employer, who wishes to work for both that employer and a new employer concurrently upon their return to the US, must apply for a new H-1B1 visa, presenting required evidence concerning the new employment to a consular post, and explaining that they intend to work for both employers. See for example [here](https://immigrationworkvisa.com/h1b1-visa/).

45 |

46 | ## Can I be self-employed while in H-1B1 status?

47 | According to the U.S. embassy in [Chile](https://cl.usembassy.gov/visas/nonimmigrant-visas/), H-1B1 workers cannot be self-employed or independent contractors. See the [answer](H-1B.md#can-i-be-self-employed-while-in-h-1b-status) to the similar question about H-1B status. Although the regulations are not crystal clear, it seems reasonable to assume that the nuances of the H-1B employer-employee relationship requirement also apply to H-1B1 status. However, note again that if you have an EAD, you can work for any employer, including being self-employed.

48 |

49 | ## How can I get an Employment Authorization Document (EAD)?

50 | The answer to this question is the same as for [H-1B](H-1B.md#how-can-i-get-an-employment-authorization-document-ead) workers.

51 |

52 | ## Can the spouse of an H-1B1 nonimmigrant obtain an H-4 EAD?

53 | The H-4 EAD program only applies to certain spouses of H-1B nonimmigrants [21]. As discussed above, the H-1B1 status is a distinct status from H-1B, and is not a subtype thereof. Therefore, an H-4 spouse of an H-1B1 nonimmigrant is not eligible for the H-4 EAD program. The H-4 spouse of an H-1B1 nonimmigrant might, however, qualify for the [compelling circumstances EAD

](H-1B.md#how-can-i-get-an-employment-authorization-document-ead).

54 |

55 | ## How can I change employers in H-1B1 status?

56 | Since, as discussed above, H-1B1 nonimmigrants are generally authorized only to work for a sponsoring employer, if an H-1B worker wants to change jobs, the new company must be one that is willing to sponsor H-1B1s. If you want to switch employers while in the US, the new employer must file a petition on Form I-129. If you intend to leave the US and then return to work for the new employer, while the Foreign Affairs Manual does not specifically cover this situation, some online resources (*e.g.*, [here](https://immigrationworkvisa.com/h1b1-visa/) and [here](https://visaguide.world/us-visa/nonimmigrant/employment/h1b/h1b1/)) indicate that it is necessary to apply for a new H-1B1 visa for the new employer, and the original H-1B1 visa will be cancelled if you no longer intend to work for the old employer.

57 |

58 | One important difference between H-1B and H-1B1 status is that an H-1B1 worker may **not** start working at the new employer while the new petition is pending. They must wait for the petition to be approved. This is because the text of INA 214(n) [13] specifically refers to the paragraph of the Immigration and Nationality Act that defines H-1B status, whereas H-1B1 status is defined in the following paragraph. The fact that H-1B1 workers do not benefit from INA 214(n) portability is also noted in the federal regulations [14]. Unfortunately, immigration lawyers providing answers on the internet often seem to believe, mistakenly, that INA 214(n) portability applies to H-1B1 workers. Thus, the options are to have the new employer file an H-1B1 petition and wait for it to be *approved* before switching to the new employer, or to leave the US and apply for a new H-1B1 visa.

59 |

60 | Since premium processing is not available for H-1B1 petitions [12], leaving the US and applying for a new H-1B1 visa for the new employer is likely to be faster than switching employers while in the US. (However, the new employer's filing of the petition does not terminate your work authorization at your old employer, so going the I-129 route does not require being temporarily unemployed; you can hand in your resignation after the new petition is approved.)

61 |

62 | If you really want to file with USCIS to change employers, then you can stay in the US while the new petition is pending, thanks to the [general rules about I-94 expiration with a pending extension](general.md#what-happens-if-my-nonimmigrant-status-expires-while-my-change-of-status-extension-of-stay-or-adjustment-of-status-application-is-pending), but again, you're not allowed to work for the new employer during that period. You can resign from your current employer, and just sit around waiting for the new petition to be approved. Because H-1B1 status is only granted in 1-year increments, by the time the petition gets approved, a substantial fraction of the 1-year period requested by the new employer will have passed already, so the new employer will also have to file an extension petition soon (they can avail themselves of the 240-day rule; see above). Despite this inconvenience, this option can be useful for H-1B1 workers who cannot travel for some reason.

63 |

64 | ## Can I apply for a green card from H-1B1 status?

65 | H-1B1 workers may be able to qualify for a green card through the same paths as [H-1B](H-1B.md) workers: that is, most often through an [employment-based category](EB.md), and most often through the same employer that is sponsoring their H-1B1 visa, but this has some risks that it is important to be aware of. This is due to two important differences between H-1B and H-1B1 status:

66 |

67 | * H-1B1 status does not permit dual intent [18], even though H-1B status does. If you are an intending immigrant, you may no longer be admitted on an H-1B1 visa or be granted any further 1-year extensions of H-1B1 status. Once you have filed for adjustment of status, you have revealed your intent as an intending immigrant.

68 | * H-1B1 status is only granted in 1-year increments, so it is quite likely for your I-94 to expire before your adjustment of status can be approved, and as explained in the previous item, further extensions are not possible.

69 |

70 | Some H-1B1 workers will accept these risks (explained in more detail in the [green card FAQ](green-card.md)), while others will take the safer route of entering the H-1B lottery and only applying for a green card once H-1B status has been secured. (Entering the H-1B lottery does not affect your ability to continue to qualify for H-1B1 status.)

71 |

72 | ## Since H-1B1 status does not permit dual intent, how can I avoid being considered an intending immigrant?

73 | The determination of whether an alien seeking an H-1B1 visa or H-1B1 status is made based on the subjective judgement of consular officials, CBP agents, and USCIS officers each time a visa, admission, or extension or change of status is sought. Thus, it's usually not possible to be absolutely certain that you will or will not be regarded as an intending immigrant. However, some important considerations are listed below:

74 |

75 | * Filing Form I-485 is the most unambiguous evidence of immigrant intent. However, having an employer file a labor certification application for you (the first step in the EB-2 and EB-3 green card process, other than National Interest Waiver cases) does not affect your ability to seek H-1B1 status since it is filed with the Department of Labor, rather than USCIS or the State Department.

76 | * Unlike applicants for B, F, or J status, an H-1B1 applicant is not explicitly required to demonstrate that they have a residence abroad that they have no intention of abandoning [1]. Therefore, the approval of the H-1B1 petition, together with the absence of factors that would arouse a suspicion of immigrant intent, is generally sufficient to satisfy [INA 214(b)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1184#b).

77 | * The Foreign Affairs Manual recognizes [19] that *"an intent to immigrate in the future, which is in no way connected to the proposed immediate trip, need not in itself result in a finding that the immediate trip is not temporary. An extended stay, even in terms of years, may be temporary, as long as there is no immediate intent to immigrate."* Therefore:

78 | * Multiple extensions and renewals are possible, but not if you appear to be using H-1B1 status to live in the US permanently in order to avoid the need to go through the green card process. It is of course quite common for people to work in the US for many years while still maintaining an intent to eventually go back to their home country. But there may come a point when, based on the subjective judgement of the officials concerned, you appear to be trying to live in the US permanently. Therefore, if you do want to live in the US permanently, you should usually start the green card process early on in order to minimize this risk.

79 | * The fact that your employer is likely to eventually sponsor you for a green card does not imply that the *immediate trip* should be denied based on immigrant intent. However, if a CBP agent asks you whether you're going to apply for a green card and you say something stupid like "yeah, my employer is probably going to start the process in a few months" then you are likely to be denied entry since it now appears that you are going to immigrate on the immediate trip.

80 |

81 | ## Is there a grace period for H-1B1 workers?

82 | Yes, an H-1B1 worker may be eligible for a grace period of up to 60 days. This is discussed [in the general FAQ](https://github.com/t3nsor/us-immigration-faq/blob/master/general.md#if-i-am-fired-from-my-job-or-quit-what-happens-to-my-status). H-1B1 is specifically listed as one of the classifications eligible for the grace period according to the regulations.

83 |

84 | During the grace period, one may transfer to another employer, change status, adjust status, or depart the US. Note however that as discussed above, there is no AC21 portability available for H-1B1 workers. Therefore, if you do choose to have a new employer file for an H-1B1 transfer within the US, you will have to remain unemployed for several months while you wait for it to be approved.

85 |

86 | ## Were H-1B1 visas affected by the work visa ban of June 22, 2020?

87 | The proclamation [16] (which expired at the end of March 31, 2021 and is thus no longer in effect) covered H-1B, H-2B, J-1, and L-1 visas. The H-1B1 visa is distinct from the H-1B visa: the above questions and answers give some examples of ways in which statutory provisions that apply to H-1B visas do *not* apply to H-1B1 visas unless explicitly specified. That is, **the H-1B1 visa is not a subtype of the H-1B visa** and therefore, as written, the proclamation did not affect the issuance of H-1B1 visas.

88 |

89 | The US embassy in Singapore initially refused H-1B1 visa applications [17] without legal basis, but later determined that H-1B1 visas were not subject to the ban [20].

90 |

91 | # References

92 | [1] INA 101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b1) ([8 USC §1101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b1)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1101#a_15_H))

93 | [2] INA 214(g)(8)(A) ([8 USC §1184(g)(8)(A)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1184#g_8_A))

94 | [3] [9 FAM 402.10-5(B)](https://fam.state.gov/fam/09FAM/09FAM040210.html#M402_10_5)

95 | [4] INA 214(i)(3) ([8 USC §1184(i)(3)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1184#i_3))

96 | [5] [INA 214(c)(1)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1184#c_1) explicitly exempts the H-1B1 classification from its petition requirement.

97 | [6] [9 FAM 402.10-5(D)](https://fam.state.gov/fam/09FAM/09FAM040210.html#M402_10_5)

98 | [7] [Instructions for Petition for Nonimmigrant Worker](https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/form/i-129instr.pdf)

99 | [8] USCIS-AFM 30.3(d)(3), [archived August 24, 2019](http://web.archive.org/web/20190824032609/https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/AFM/HTML/AFM/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-12693/0-0-0-12947.html)

100 | [9] *Ibid.*, (d)(7)(A)

101 | [10] INA 214(g)(8)(C) ([8 USC §1184(g)(8)(C)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1184#g_8_C))

102 | [11] [8 CFR §274a.12(b)(9)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/274a.12#b_9)

103 | [12] https://www.uscis.gov/i-129-addresses

104 | [13] INA 214(n) ([8 USC §1184(n)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1184#n))

105 | [14] [20 CFR §655.700(d)(1)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/20/655.700#d_1)

106 | [15] [8 CFR §274a.12(b)(20)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/274a.12#b_20)

107 | [16] [Proclamation Suspending Entry of Aliens Who Present a Risk to the U.S. Labor Market Following the Coronavirus Outbreak](https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-suspending-entry-aliens-present-risk-u-s-labor-market-following-coronavirus-outbreak)

108 | [17] https://twitter.com/gsiskind/status/1276381233602269185

109 | [18] See [9 FAM 402.10-10(A)(a)](https://fam.state.gov/fam/09FAM/09FAM040210.html#M402_10_10). Note that as the State Department's policy in this case is derived from INA 214(b) and 214(h), USCIS is bound to follow similar policy.

110 | [19] [9 FAM 402.10-5(F)(a)](https://fam.state.gov/fam/09FAM/09FAM040210.html#M402_10_5_F)

111 | [20] https://twitter.com/gsiskind/status/1278766478477713409

112 | [21] [8 CFR §274a.12(c)(26)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/274a.12#c_26)

113 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/green-card.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ## Is applying for a green card the only way to live in the US permanently?

2 | Yes, with a few exceptions. Almost all nonimmigrant statuses are for a limited period of time and require "nonimmigrant intent", which means that DoS and CBP have discretion to stop granting you visas/status if they can see that you are trying to live in the US permanently. Some exceptions include:

3 | * [O-1](O-1.md) status is exempt from the requirement to maintain a residence abroad [1], and can therefore be renewed indefinitely in 3-year increments. However, you must continue to work in the area of extraordinary ability for as long as you want to remain in O-1 status.

4 | * American Indians born in Canada may live in the US permanently and are immune to deportation [2][3].

5 | * Most citizens of the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Palau may live and work in the US indefinitely under the terms of the Compact of Free Association [4][5].

6 | * There are a few paths to US citizenship that bypass the usual requirement of first becoming a permanent resident. The most common one involves applying for naturalization during a temporary visit to the US when you have a US citizen parent (possibly an adoptive parent) who resides with you outside the US [61]. The others are more obscure.

7 |

8 | ## Are there any reasons why I might not want a green card?

9 | Yes. Lawful permanent resident (LPR) status in the United States confers both rights and responsibilities. Here are some reasons why you might not want to become an LPR:

10 | * Permanent residents, if male and between the ages of 18 and 26, are required to register for the Selective Service [6].

11 | * An LPR is subject to taxation as a resident alien even if they reside outside the US for most of the year [7].

12 | * You must actually reside in the US in order to maintain the rights associated with LPR status. If you abandon your residence in the US, you will need to file Form I-407 to renounce that status before you can be readmitted to the US as a nonimmigrant. If you have been an LPR for 8 or more years at the time when you give up that status, you may be subject to an expatriation tax [8].

13 |

14 | ## How can I apply for lawful permanent residence (green card status)?

15 | You can qualify to become an LPR as:

16 | * a family-based immigrant [12][13],

17 | * an employment-based immigrant [14],

18 | * a diversity immigrant [15],

19 | * an asylee or refugee [16], or

20 | * a spouse or child of someone who falls into one of the above categories.

21 |

22 | There are a few other, less common routes to LPR status that have been omitted from the above list. Since the Immigration Act of 1990, there is no general category you can "wait in line" for. You need to qualify under one of the specific provisions of the law. [17]

23 |

24 | In family-based and employment-based cases, you must have a petition filed by your sponsoring family member or sponsoring employer (some employment-based categories allow self-petition) and approved by USCIS in order to establish your eligibility [18][19]. For all employment-based categories and most family-based categories, there is an annual quota, so following the approval of the petition, you may need to wait months or years before it becomes your turn to apply for LPR status.

25 |

26 | When the time finally comes for you to apply for LPR status, you can obtain that status either by applying for an immigrant visa and using it enter the US [9] or by applying for adjustment of status while already in the US [10]. For employment-based applicants, the adjustment of status route is more common, since the applicant will usually already be working for the sponsoring employer in a nonimmigrant status at the time when they become eligible to apply for LPR status.

27 |

28 | Although adjustment of status applicants don't receive immigrant visas, it is customary to refer to both types of immigrants as immigrant visa applicants. For example, a petition such as an I-130 (family-based) or I-140 (employment-based) is referred to as an "immigrant visa petition" even though, once approved, it can be used for either an immigrant visa application *or* adjustment of status. Similarly, limitations on numbers of immigrant visas that may be issued per year also apply to adjustment of status applicants [27].

29 |

30 | You become an LPR, and are entitled to the associated rights and privileges, as soon as you are admitted under an immigrant visa or your adjustment of status is approved. However, it takes a few months to produce the plastic green card bearing your photo and other information, which will be mailed to you when it is ready.

31 |

32 | ## What is the typical application process for employer-sponsored immigration?

33 | See [the EB FAQ](EB.md).

34 |

35 | ## What is the 7% per-country cap?

36 | This is a rule that, out of the total quota of employment-based and family-based visas available per fiscal year, each country's natives are initially limited to receiving up to 7% of those visas [22]. (If this rule would result in some visas going unused, then the remaining visas can be issued in excess of the 7% limit.) The practical details of how the State Department enforces this limit are complex and not fully understood, but the overall result is long waiting times for applicants from certain countries, if they are applying for an immigrant classification that many other people from their country are also applying for. For example, family-based waiting times are very for natives of Mexico, and employment-based waiting times are very long for natives of India.

37 |

38 | ## Why are the per-country quotas on immigration based on country of birth rather than country of citizenship?

39 | It is a common practice for countries to treat foreign nationals differently depending on the specific foreign country of nationality: for example, almost all countries maintain a list of other countries whose citizens they grant visa-free access to. (The US Visa Waiver Program is no exception: citizens of most European countries, and a few other rich countries such as Australia and Japan, may travel to the US for up to 90 days for business or pleasure without obtaining a visa.) Some countries also have a simple path to permanent residence for citizens of other specified countries: the EU for other EU countries, Australia and New Zealand for each other, and so on. However, discrimination based on country of birth is a quirk of the American immigration system that exists partially for historical reasons and partially for political reasons.

40 |

41 | Historically, country of birth quotas were originally introduced as part of the Immigration Act of 1924, which is infamous for including the National Origins Formula

. The purpose of the National Origins Formula was to attempt to revert the racial demographic profile of the United States to be more similar to what it had been a few decades prior, when most immigrants were from northern and western Europe. As such, the National Origins Formula was different from the current quota system in one important way: it had a different quota for each country, and immigration from most of Asia was completely banned. In such times, nationality was a fuzzier concept than it is today (in part due to colonialism) and many people around the world had no nationality; it seems likely that Congress decided that charging immigrants to the quota of their country of birth would be the simplest and cleanest way to accomplish their racial demographic shaping objectives.

42 |

43 | The National Origins Formula was repealed by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which set the current 7% quota for immigrants born in any one foreign country (though *total* quotas were later adjusted by the Immigration Act of 1990). It's not clear whether there was any debate at the time about whether the quota system should have been changed to be based on country of nationality rather than country of birth.

44 |

45 | In the modern era, debates about the per-country quota tend to be centered around whether the rule should be abolished, at least for employment-based immigrants (some proposals also raise the per-country quota for family-based immigrants from 7% to 15%). Proponents of maintaining the per-country quotas insist that they are necessary in order to preserve diversity and avoid the formation of ethnic enclaves within the US. There is no significant advocacy for changing the formula to be based on country of citizenship, since opponents of the per-country quota contend that the US should simply accept a number of the most qualified immigrants from all over the world instead of limiting the number that can come from specific countries.

46 |

47 | ## Can I be charged to the quota of a country other than my country of birth?

48 | As explained above, becoming a citizen of another country doesn't affect which country you're charged to for the purposes of the 7% per-country limitation. However, under some conditions, it is possible to be charged to a different country. If your country of birth is different from that of both of your parents, and neither parent had a residence in your country of birth at the time of your birth, you may be able to be charged to one of your parents' countries of birth instead. Also, you can be "cross-charged" to your spouse's country of birth if it is different from yours [20]. The *Foreign Affairs Manual* explains that, for example, an EB-2 applicant born in India and has a spouse born in France could elect to be charged to France, thus having their priority date become current sooner [21]. (However, if your plan is to find someone to marry specifically to speed up your green card process, why not just marry an American?)

49 |

50 | ## What do I need to do in order to maintain my LPR status?

51 | Once you are granted LPR status, you must observe many rules in order to avoid losing that status, some of which are listed here:

52 | * Maintain your domicile in the US by living in the US and only making temporary trips abroad. This is a complex topic for which many other resources are available online, so we won't have much more to say about this here.

53 | * Inform DHS of any change of address in the United States by filing [Form AR-11](https://www.uscis.gov/ar-11) with USCIS.

54 | * This is required by law and failing to do so could theoretically, by itself, serve as a ground for deportation [28]. While I'm not aware that anyone has ever been deported for this reason alone, I do not recommend handing the current administration an excuse to deport you on a silver platter.

55 | * More practically, if USCIS or ICE needs to send you any written communication, they will send it to your address on file. Failure to receive such communication, such as a Notice To Appear, could have adverse consequences for your immigration status.

56 | * Keep in mind that there are various criminal convictions that can serve as grounds for inadmissibility and/or deportation [29][30]. If you consider deportation to be a more serious punishment than incarceration, you may want to be more careful than you would otherwise be when doing anything that could possibly lead to a criminal conviction.

57 | * Do not attempt to vote. While this may seem obvious, it's easy to accidentally sign a petition for a ballot proposition (particularly in California). You should keep in mind that this is not allowed [31] until you become a US citizen and register to vote.

58 | * Never misrepresent yourself as a US citizen [32]. You are already entitled to most of the rights that US citizens enjoy, so there is usually no reason to do so. For example, LPRs can engage in employment, invest, obtain mortgages, and purchase firearms on the same terms as US citizens.

59 | * Never enter the United States other than at a designated port of entry [33].

60 | * When entering the United States, have in your possession your valid unexpired green card or temporary I-551, re-entry permit, or returning resident visa [34].

61 | * If your LPR status was granted on a conditional basis (indicated by a green card that expires 2 years after the date on which you become an LPR), you must apply to remove conditions during the 90-day period preceding said expiration [37][38][39]. Failure to do so will result in the expiration of your status, upon which you may be deported.

62 | * If you are issued a Notice To Appear, you **must** attend (either personally or in some other prescribed manner) even if you are certain that you are not removable. Failure to attend can result in being barred from the US for 5 years [41]. If you don't attend, and the removal proceedings conclude that you are removable, then you will be ordered removed *in absentia*, which may result in being barred from the US for 10 years [40][42].

63 |

64 | If the above rules sound burdensome to you, consider applying for naturalization once you become eligible. Naturalized US citizens are not subject to any of these restrictions.

65 |

66 | ## Do I need to carry my green card with me at all times?

67 | Failure to carry your green card or other evidence of your LPR status while in the United States is not a deportable offense, but is a misdemeanor [35]. While few people are convicted for failing to carry their green card, it's quite possible that ICE agents demand to see your green card, refuse to believe you when you say you left it at home, and place you under detention, releasing you only once they are satisfied that you are an LPR (and there's no telling how long that will take). Why expose yourself to that risk?

68 |

69 | ## What happens when my green card expires?

70 | If you have conditional status, your green card will expire at the same time as your status---namely, 2 years after you become an LPR. You must apply to have the conditions removed [using the appropriate form](https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/after-green-card-granted/conditional-permanent-residence). Upon approval of this application, you will receive a green card valid for 10 years. Failure to do so can result in removal from the United States [37].

71 |

72 | If your 10-year green card is expiring, you are required to apply for a new card [36] using [Form I-90](https://www.uscis.gov/i-90). The expiration of a 10-year green card does not result in the loss of LPR status (see *e.g.,* [here](https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/pressrelease/GreenCardRenewal_110702.pdf)), but an expired green card generally cannot be used as proof of LPR status, so failure to renew your expired card will make life more difficult for you.

73 |

74 | ## If I give up my green card, will it prevent me from applying for a green card in the future?

75 | The voluntary loss of LPR status (*i.e.,* not as a result of being deported or removed from the United States) is not among the grounds of inadmissibility set out in INA 212(a) ([8 USC §1182(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1182#a)), and therefore does not, in general, act as a bar to future admission to the US as a nonimmigrant or as an immigrant, provided that you meet all the necessary qualifications, just as is required of any other alien who was not previously an LPR.

76 |

77 | There is a single exception: if you, as an LPR, leave the US in order to avoid the draft, you become permanently ineligible to immigrate to the US [23][24]. It is possible to return to the US temporarily (*i.e.,* as a nonimmigrant), but a waiver is required [25]. Yikes.

78 |

79 | If you wish to return to the US as an immigrant in the future after giving up LPR status, you will need to go through the whole process all over again. You cannot reuse the priority date that you used for your previous immigrant visa application when you are applying for your new immigrant visa [26]. You might wonder if there's a loophole: if you had two I-140s approved, and you used the priority date of the earlier one for your immigrant visa application, becoming an LPR, could you later use the priority date of the later one for a subsequent immigrant visa application? The answer doesn't seem to be written down anywhere, and no immigration lawyer I spoke to had ever heard of such an unusual case. All I can say is that it would be unwise to expect this to be allowed. You should simply assume that you will have to start from scratch, with none of your old priority dates being available.

80 |

81 | ## Can I bring my family with me when I immigrate to the US?

82 | This is a complicated topic. The general principles are as follows:

83 | * Terminology: the alien who directly qualifies for an immigrant visa or adjustment of status is known as the *principal applicant*. Some immigration categories allow *derivative applicants*: that is, additional individuals, namely the spouse and children of the principal, are eligible to immigrate as well by virtue of their relationship to the principal. Some categories do not allow derivatives. For example, if Form I-140 was filed on your behalf by your employer, then you are a principal applicant and your spouse and children can be included as derivatives; they derive their eligibility from you, rather than through their own employment.

84 | * In the Immigration and Nationality Act, "child" means unmarried child under the age of 21, including stepchildren and adopted children under some circumstances [44]. A child who is married or over the age of 21 cannot be included as a derivative. Instead, you may eventually be able to sponsor them as a principal in a family-based immigration category [13], at which time they can bring their own derivatives. However, the waiting time for this is often years or decades.

85 | * Derivative applicants outside the US may either accompany the principal (enter the US on immigrant visas at the same time as the principal) or follow to join (enter the US on immigrant visas after the principal has immigrated) [43][45]. Derivative applicants in the US may file for adjustment of status either concurrently with the principal or at a later time [46].

86 | * Your spouse can only qualify as a derivative if you married them before you entered the US on an immigrant visa [45] or before your adjustment of status was approved [46]. A similar rule exists for children, but there are exceptions, for which see [45]. If you get married after you become an LPR, your spouse cannot qualify as a derivative, and must instead be sponsored as a principal. Since, at the time of writing, there is roughly a 2-year backlog for spouses of LPRs [47], you are advised to consider getting married before you acquire LPR status.

87 | * A child born outside the US to a mother who is already an LPR does not need to receive an immigrant visa as a derivative, but may instead be admitted to the US as an immigrant when accompanying the mother on her first return to the US after the birth of the child [48]. (A child born *in* the US, on the other hand, is already a citizen.)

88 |

89 | ## Which immigrant classifications allow family members to be derivative beneficiaries?

90 | In this answer, we will only cover the previously mentioned [routes to LPR status](#how-can-i-apply-for-lawful-permanent-residence-green-card-status). Eligibility for derivative classification, as a spouse or child of the principal applicant, is subject to the caveats discussed above.

91 | * A principal classified as the immediate relative of a US citizen (spouse, unmarried child under 21, or parent) cannot have derivative benficiaries; their spouses and children must be separately sponsored as principals [52]. (We defer further discussion of this topic to a possible future section of the FAQ dealing specifically with family-based immigration.)

92 | * [Employment-based](EB.md) immigrants, that is, immigrants with classification EB-1, EB-2, EB-3, EB-4, and EB-5, can have derivative beneficiaries [43].

93 | * Family-based preference immigrants (F1, F2A, F2B, F3, or F4) can have derivative beneficiaries [43]. However, F1 and F2B immigrants cannot have derivative spouses since those classifications require the principal to be unmarried.

94 | * Diversity immigrants can have derivative beneficiaries [43].

95 | * Asylees and refugees can have derivative beneficiaries [49][50]. The derivatives are accorded the same status as the principals, and therefore must apply for LPR status after one year, just as the principal does [51].

96 |

97 | ## What happens when an adjustment of status application is denied?

98 | Denial of Form I-485 results in your status not being adjusted; for example, if you were in H-1B status at the time when Form I-485 was denied, then you continue in H-1B status. However, if your nonimmigrant status has expired by the time that Form I-485 is denied, then you are in trouble, since USCIS has decided to start referring to removal proceedings all denied I-485 applicants who are unlawfully present upon denial [60]. It is therefore advisable to, whenever possible, keep renewing your nonimmigrant status while waiting for your I-485 to be adjudicated. (Unfortunately, there are some nonimmigrant classifications, such as K-1 and K-2, for which this isn't possible.)

99 |

100 | ## How can I get an Employment Authorization Document (EAD)?

101 | There are many ways to get an EAD, but only two will be discussed in this section of the FAQ.

102 |

103 | Aliens applying for adjustment of status can apply for an EAD [55]. USCIS allows Form I-765, Application for Employment Authorization, to be filed either concurrently with Form I-485, or while Form I-485 is pending [56]. This should be indicated as category (C)(9) on form I-765 [56]. The only requirement to apply for a (C)(9) EAD is that you have filed Form I-485 and Form I-485 is still pending. In nearly all cases, form I-765 is approved before form I-485, which provides the alien with temporary work authorization while they wait for their form I-485 to be approved. Those who are interested in obtaining an EAD would be well advised to apply sooner rather than later, because it can take several months for the EAD to be issued.

104 |

105 | As an exception, asylees and refugees qualify for employment authorization "incident to status" [59], and even though they may have a pending I-485, they should apply for employment authorization on the basis of their status, not on the basis of the pending I-485 [56].

106 |

107 | ## If my I-485 is denied, does my EAD get revoked?

108 | USCIS may revoke an EAD when it determines that a change in circumstances results in you no longer being eligible for employment authorization [57]. Thus, if you received an EAD due to a pending I-485 and the I-485 is denied, USCIS has grounds to revoke the EAD upon written notice, which gives you 15 days to respond (for example, by filing a motion to reopen the adjustment case). Some immigration lawyers claim that regardless of whether or not USCIS notifies you that they are revoking your EAD, the denial of Form I-485 results in automatic revocation of the EAD. Others, however, recognize that federal regulations explicitly require written notice of revocation (see, *e.g.*, [Silzer, 2009](http://ilw.com/articles/2009,0723-silzer.shtm)).

109 |

110 | Note, however, that if you are placed in removal proceedings upon the denial of the adjustment of status application (see above), then this has a side effect of automatically revoking your EAD; USCIS is not required to send notice of revocation in such cases [58].

111 |

112 | ## Has USCIS stopped approving I-485s because of the immigrant visa ban of April 22, 2020?

113 | No. The proclamation in question [62] applies to the issuance of immigrant visas at consular posts. It does not prevent USCIS from issuing green cards to individuals who have applied for adjustment of status from within the US. There had been some [speculation](https://www.rollcall.com/2020/06/12/administration-puts-hold-on-green-card-requests-from-us/) that I-485 processing had been paused, but the author of that article later posted an [update](https://www.rollcall.com/2020/06/17/immigration-agency-resumes-processing-u-s-based-green-cards/) clarifying that the supposed pause on I-485 adjudication was related to prioritizing limited USCIS resources and was not related to the immigrant visa ban. I-485s for all categories continued to be processed despite the proclamation of April 22, 2020.

114 |

115 | The immigrant visa ban was rescinded on February 24, 2021.

116 |

117 | # References

118 | [1] INA 101(a)(15)(O)(i) ([8 USC §1101(a)(15)(O)(i)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1101#a_15_O_i))

119 | [2] INA 289 ([8 USC §1359](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1359))

120 | [3] *Matter of Yellowquil*, 16 I. & N. Dec. 576 (BIA 1978) (https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/eoir/legacy/2012/08/17/2664.pdf)

121 | [4] [48 USC §1901](https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2009-title48/html/USCODE-2009-title48-chap18-subchapI-partA-sec1901.htm)

122 | [5] [48 USC §1931](https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2009-title48/html/USCODE-2009-title48-chap18-subchapII-partA-sec1931.htm)

123 | [6] [50 USC §3802(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/50/3802)

124 | [7] This is the so-called "green card test", codified at [26 USC §7701(b)(1)(A)(i)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/7701#b_1_A_i)

125 | [8] [26 USC §877(e)(2)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/877#e_2)

126 | [9] [8 CFR §211.1(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/211.1#a)

127 | [10] INA 245(a) ([8 USC §1255(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1255#a))

128 | [11] [8 CFR §245.1(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/245.1#a)

129 | [12] INA 201(b) ([8 USC §1151(b)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1151#b))

130 | [13] INA 203(a) ([8 USC §1153(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1153#a))

131 | [14] INA 203(b) ([8 USC §1153(b)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1153#b))

132 | [15] INA 203(c) ([8 USC §1153(c)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1153#c))

133 | [16] INA 207–209 ([8 USC §1157–1159](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/chapter-12/subchapter-II/part-I))

134 | [17] INA 201(a) ([8 USC §1151(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1151#a))

135 | [18] INA 204(a) ([8 USC §1154(a)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1154#a))

136 | [19] [8 CFR §204.1](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/204.1)

137 | [20] INA 202(b) ([8 USC §1152(b)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1152#b))

138 | [21] [9 FAM 503.2-4(A)(h)](https://fam.state.gov/FAM/09FAM/09FAM050302.html)

139 | [22] INA 202(a)(2) ([8 USC §1152(a)(2)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1152#a_2))

140 | [23] INA 212(a)(8)(B)([8 USC §1182(a)(8)(B)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1182#a_8_B))

141 | [24] [9 FAM 305.2-10(B)](https://fam.state.gov/FAM/09FAM/09FAM030502.html)

142 | [25] [9 FAM 305.3-10(B)](https://fam.state.gov/FAM/09FAM/09FAM030503.html)

143 | [26] [9 FAM 503.3-3(A)](https://fam.state.gov/FAM/09FAM/09FAM050303.html)

144 | [27] INA 245(a)(3) ([8 USC §1255(a)(3)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1255#a))

145 | [28] INA 237(a)(3)(A) ([8 USC §1227(a)(3)(A)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1227#a_3_A))

146 | [29] INA 237(a)(2) ([8 USC §1227(a)(2)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1227#a_2))

147 | [30] INA 212(a)(2) ([8 USC §1182(a)(2)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1182#a_2))

148 | [31] INA 237(a)(6) ([8 USC §1227(a)(6)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1227#a_6))

149 | [32] INA 237(a)(3)(D)(i) ([8 USC §1227(a)(3)(D)(i)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1227#a_3_D_i))

150 | [33] INA 212(a)(6)(A)(i) ([8 USC §1182(a)(6)(A)(i)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1182#a_6_A_i))

151 | [34] INA 212(a)(7)(A)(i)(I) ([8 USC §1182(a)(7)(A)(i)(I)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1182#a_7_A_i_I))

152 | [35] INA 264(e) ([8 USC §1304(e)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1304#e))

153 | [36] [8 CFR §264.5(b)(2)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/264.5#b_2)

154 | [37] INA 237(a)(1)(D) ([8 USC §1227(a)(1)(D)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1227#a_1_D))

155 | [38] [8 USC §1186a](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1186a)

156 | [39] [8 USC §1186b](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1186b)

157 | [40] [8 USC §1229a(b)(5)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1229a#b_5)

158 | [41] INA 212(a)(6)(B) ([8 USC §1182(a)(6)(B)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1182#a_6_B))

159 | [42] INA 212(a)(9)(A) ([8 USC §1182(a)(9)(A)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1182#a_9_A))

160 | [43] INA 203(d) ([8 USC §1153(d)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1153#d))

161 | [44] INA 101(b)(1) ([8 USC §1101(b)(1)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1101#b_1))

162 | [45] [9 FAM 502.1-1(C)(2)(b)](https://fam.state.gov/FAM/09FAM/09FAM050201.html)

163 | [46] [Instructions for Form I-485](https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/form/i-485instr.pdf)

164 | [47] [January 2019 visa bulletin](https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal/visa-law0/visa-bulletin/2019/visa-bulletin-for-january-2019.html)

165 | [48] [8 CFR §211.1(b)(1)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/211.1#b_1)

166 | [49] INA 207(c)(2)(A) ([8 USC §1157(c)(2)(A)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1157#c_2_A))

167 | [50] INA 208(b)(3)(A) ([8 USC §1158(b)(3)(A)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1158#b_3_A))

168 | [51] INA 209(b)(3) ([8 USC §1159(b)(3)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1159#b_3))

169 | [52] [8 CFR §204.2(a)(4)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/204.2#a_4)

170 | [53] *Ibid.*, (d)(4)

171 | [54] *Ibid.*, (f)(4)

172 | [55] [8 CFR §274a.12(c)(9)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/274a.12#c_9)

173 | [56] [Instructions for Form I-765](https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/form/i-765instr.pdf)

174 | [57] [8 CFR §274a.14(b)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/274a.14#b)

175 | [58] *Ibid.*, (a)

176 | [59] [8 CFR §274a.12(a)(3–5)](https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/8/274a.12#a)

177 | [60] [Notice to Appear Policy Memorandum](https://www.uscis.gov/legal-resources/notice-appear-policy-memorandum)

178 | [61] INA 322 ([8 USC §1433](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1433))

179 | [62] [Proclamation Suspending Entry of Immigrants Who Present Risk to the U.S. Labor Market During the Economic Recovery Following the COVID-19 Outbreak](https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-suspending-entry-immigrants-present-risk-u-s-labor-market-economic-recovery-following-covid-19-outbreak/)

180 | [63] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/02/24/a-proclamation-on-revoking-proclamation-10014/

181 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/TN.md:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 | ## Who qualifies for TN status?

2 | TN status is limited to citizens of Canada and Mexico [1]. Permanent residents of Canada, for example, do not qualify [4]. However, citizens of Canada and Mexico admitted in TN status can bring along their [dependents](general.md#as-a-nonimmigrant-can-i-bring-my-family-with-me-to-the-us) regardless of said dependents' nationalities [5].

3 |

4 | A TN worker must be coming to the US as a "professional" in one of the professions listed in Appendix 1603.D.1 of NAFTA [2] and must meet the minimum credential requirement set out therein. This list of qualifying professions and minimum credentials is reproduced in the federal regulations [3]. Self-employment is not permitted [4][7].

5 |

6 | ## Does my degree have to be in the same field as my occupation?

7 | Many of the professions that qualify for TN status require a bachelor's degree or similar credential. There is no specific requirement regarding how closely related the major area of study for the degree must be to the profession the alien intends to engage in, either in the NAFTA text [2], or in the federal regulations [3], although the State Department does seem to take the view that there must be "significant overlap" [9]. A common example is that individuals with a bachelor's degree in Mathematics or Physics often receive TN status to engage in software engineering. However, when the degree appears unrelated to the profession, there is a significant probability of being denied admission at the port of entry, or being issued a Request for Evidence (RFE) by USCIS.

8 |

9 | As such decisions made by CBP officers are unpredictable to a certain extent, it is normally recommended that if a US employer seeks to employ someone in TN status who has an unrelated degree, the employer should file an I-129 petition with USCIS (see below) rather than having the question of the prospective employee's entitlement to TN status determined at the port of entry. This [often](https://www.google.com/search?q=TN+RFE+unrelated+degree) results in an RFE, but this can often be overcome. The legal justification for the RFE is that federal regulations require that the TN nonimmigrant must demonstrate "status as a professional" [6] which can be viewed as implicit within NAFTA, as an unqualified person cannot "engage in business activities at a professional level". While a bachelor's degree in a *related* field may meet both the explicit requirement of a degree *and* the additional requirement of status as a professional, a degree in an unrelated field may only satisfy the first criterion. Therefore, overcoming the RFE requires additional evidence that the alien has the status of a professional in the classification sought. See [8] for more detail.

10 |

11 | ## What is the advantage of TN status over H-1B?

12 | There are at least two significant advantages.

13 |